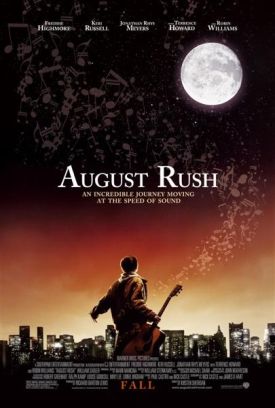

August Rush

There’s just one problem with August Rush, Kirsten Sheridan’s determinedly inspirational and occasionally charming fable of an orphan boy who finds his parents through music. It doesn’t look real. But then who minds about that anymore? The boy is played by Freddy Highmore (“Finding Neverland, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory), who may just be the cutest kid ever to appear on film. He tells us in voiceover: “I believe in music the way some people believe in fairy tales.” Huh? Music is real and fairy tales are not. To believe in the latter is to be delusional; to believe in the former is meaningless. But it turns out to be true. He believes in music as a fairy tale. So do the film-makers — or at least they pretend they do. Music here has magical powers. Music even without magical powers can be pretty great, I’d have thought, but the corrupting touch of fantasy serves as a poor apology for not thinking them quite great enough.

The magic consists of invisible lines of force, symbolized by musical talent, which have the power to draw lost parents and children back together again. The parents are Lyla and Louis, played by Keri Russell and Jonathan Rhys Meyers, the one a cello superstar in the making and the other a rock musician with all the moodiness and presumptive dark genius — we don’t see enough of his musical product to judge for ourselves — that customarily go with that job description, at least in the movies. They meet at a party and have a one-night stand. Through a series of accidents and the machinations of Lyla’s father (William Sadler) they are parted, and Louis never learns that Lyla has become pregnant. She has an accident and is in a coma when the child is born. When she wakes up, her father tells her the child died, but really he forged her signature and shipped it off to an orphanage.

Is that unbelievable enough for you? Just wait. Fast forward eleven years. The child, a victim of bullying in the orphanage because he claims to be able to “hear” his lost parents, runs away to New York City. Meanwhile, even as he is supposedly able to hear his parents among a number of other cosmic musical effusions, his bereft mommy learns that he is alive, though she knows not where. “I know it sounds crazy,” she says, “but I can hear him! I swear I can hear him!” Whenever anyone in the movies says, “I know it sounds crazy,” it’s a pretty reliable indication that it is crazy — but that they’re going to ask you to believe it anyway. Crazy people in the movies become prophets and seers, I take it, because everybody likes to identify himself with the idiosyncratic genius whom no one takes seriously but who turns out to be right.

Another such character is the modern-day Fagin called Wizard (Robin Williams) who takes the runaway in. He manages a stable of children who work the streets of Greenwich Village not as pickpockets but as buskers. On the runaway’s first day among them he learns — as does Wizard — that he is a musical prodigy. Wizard gives him the name August Rush and hopes to exploit his earning potential on the streets. He also tells him that “You’ve got to love music more than you love food. More than life. More than yourself.” That sounds about right to August, though maybe it is a little over the top for any other would-be prodigies in the audience.

Wizard is meant to be an ambiguous figure, both inspirational and exploitative. Robin Williams is said to have modeled the character on the pop musician Bono. This doesn’t sound like a compliment to me, but perhaps Bono fans will understand. August escapes from the exploitation, learns to read and write music in the space of a single day and, a day or two after that, so impresses the faculty of the Juilliard School that, having dropped everything to interview him, they admit him on the spot. In a few more days the first major composition by August Rush is advertised as the featured work on the program of a concert in Central Park by the New York Philharmonic.

Hey, it could happen! One of Wizard’s dicta is that music is “harmonic connection between all living beings.” Yet the only connection we see is between this musical genius and his genius parents. To say that the rest of us just aren’t listening, as both Wizard and August do, is a bit of silliness meant to disguise (albeit ineffectively) the fact that August is a sort of super-hero, a fantasy figure who has slipped the surly bonds of practice and study that, in the real world, we know is necessary even to genius. A word of advice for the film-makers. When it comes to magic, a little goes a long way. If the magic comes unexpectedly in an otherwise realistic context, it has much more impact than when everything is magical, as it pretty much is here. But fantasy is like a drug: the more we have, the more we want.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.