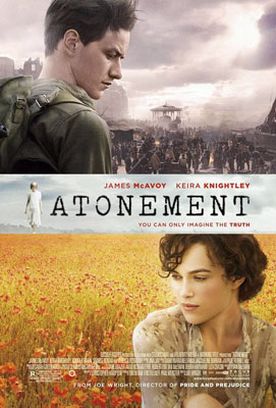

Atonement

Those who have read Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement, published in 2001, will know that there is a kind of trick or catch in the ending which some people find annoying and some, well, don’t. The same is true of the movie version by Christopher Hampton (writer) and Joe Wright (director). Those who were annoyed by the novel will probably be infuriated by the movie. I am one such person. Though I thought the book interesting and well-written, the ending spoiled it for me. Obviously, I can’t exactly explain why without giving away too much, but I think I can reveal this much. Mr Wright, like Mr McEwan before him, asks us to take fantasy as a consolation or apology for the unbearable poignancy of the story he has to tell. To me that is the reverse of a consolation. Instead, it makes a mockery of the artist’s own creation by treating it only as an excuse for a demonstration of his compassion and other fine feelings.

Opening in a British country house in 1935, it concerns a false accusation brought by Briony Tallis (Saoirse Ronan), a thirteen year old girl with an overactive imagination, against a young man named Robbie Turner (James McAvoy), who ends up spending several years in jail as a result. There is an element of class in the relationship between the two. Briony’s family are rich; Robbie is the son of their housekeeper. His education has been paid for by Briony’s father, and he has always been treated practically as one of the family. For them to believe Briony’s accusation is also to believe that he has been guilty of monstrous ingratitude to them. On his side of things, he can’t help but see the accusation as having been perpetrated by the family’s pampered darling, her native powers of fancy expanded to dangerous proportions by the faux-genteel romance literature she is so fond of and the kind of moralism once associated with the upper classes.

On the bare word of such an unreliable witness as that, they are all — or all except for Briony’s older sister, Cecilia (Keira Knightley) — ready to throw their low-born hanger-on to the wolves. You allow yourself to think that your class origins don’t matter to them, but then you find that they do. And how! Briony’s accusation comes simultaneously with Cecilia’s and Robbie’s discovery that they are in love with each other, and it results in Cecilia’s permanent estrangement from the rest of her family. Needless to say, it is Robbie’s and Cecilia’s point of view that both the novel and the film adopts as its own. By the time she reaches the age of 18 Briony — now played by Romola Garai — realizes the horrible mistake she has made and the dreadful price Robbie has paid for it. She seeks to make amends, but it is too late.

The title, Atonement, is therefore ironic. Real atonement for her sin was impossible, so Mr McEwan offered us the novel itself, re-imagined as what Briony herself would have written after she grew up (as he tells us she did) to become a novelist, and this novel is itself intended as her atonement. What she couldn’t do in her (fictional) life, she could in her (equally fictional) fiction. The movie goes even farther than this by bringing the aged Briony, played by Vanessa Redgrave, onto a TV talk show to make explicit her view of the redemptive power of art and so to spell out the McEwan “message” so that the cinema audience, presumably slower on the uptake than readers of literary fiction, will make no mistake about it.

Of course, if it’s the redemptive power of art that is your idea, a movie offers far more opportunities for the display of highly-wrought artistry than a novel, and Messrs. Hampton and Wright seem to have seized most of them. Extreme close-ups and night scenes with weird light effects help to create disorienting, dream-like effects, as do repeated episodes which tell of the same events from different points of view. What really happened? We are meant to be as much in the dark as the characters. On the fateful day which will determine everything that follows, the camera seems drunk on the lushness of its images, drawing out wherever possible the sensuousness of opera (La Boh me), smoke, sun, water, sex (suggested) and even typewriting in an extreme closeup of the physical impression of letters — in particular the letters of one word whose galvanizing effect on Briony is what leads to her false certainty — being formed as the keys strike the paper.

All this artiness struck me as being Oscar-bait, as did the film’s transition to an epic scale in its second half. For after Robbie’s arrest, it cuts to the British evacuation from Dunkirk five years later where, after having been released from jail on the outbreak of war, he turns up again. This scene naturally produces many spectacular visual effects. Yet even there, the moral clarity usually thought to attend those events is blurred. Everything is reduced to an immediate sensory level. For me the unsatisfactoriness of this treatment was summed up by the scene in which a group of soldiers on the beach are seen singing one of the most beautiful of English-language hymns, Whittier’s “Dear Lord and Father of Mankind,” and the sound is muffled and mixed in with the ambient sounds of explosions and machinery. OK, OK! I get it! Faith and hope are obscured by disaster. But, like those soldiers, I thought that the hymn alone would have better expressed the reality of the scene.

At times it seems that Mr Wright, like Briony in her novelist’s old age, thinks that by constantly calling our attention to the gorgeousness and excitement of his images, he can make us forget, or at least more easily bear, the heartbreak in the narrative they ostensibly serve. But this is art getting above itself. He, like Mr McEwan, should have more respect for their characters than that. To make the story of Robbie and Cecilia into the story of Briony’s attempt to turn her guilt and sorrow into art is to wrong them again, not to make up for the first wrong.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.