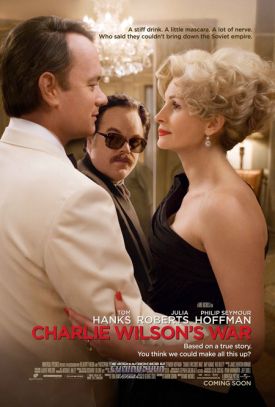

Charlie Wilson’s War

It may at first seem surprising that Charlie Wilson’s War, written by Aaron Sorkin (“The West Wing”) and directed by Mike Nichols, is being slotted into the media’s narrative about the box-office failure of a number of recent movies about the Iraq war. After all, this film is set decades ago and concerns itself with a completely different war, the one occasioned by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. No matter. According to The New York Times, “A mere whiff of more depressing headlines out of the Middle East may be enough to drive some people home to watch a DVD of the Yule log.” That, in its view, is what happened to such movies as Lions for Lambs and Rendition. Yet if Charlie Wilson’s War is successful, they’ve got an explanation for that too. It will show that “You can make a movie that is relevant and intelligent — and palatable to a mass audience — if its political pills are sugar-coated.”

In other words, what doomed Lions for Lambs and Rendition was too much truth, not enough sugar-coating. Such a belief is itself a sugar-coating of the unpalatable truth that, in spite of Hollywood’s best efforts, American audiences still like to see movies in which American forces are the good guys and they defeat America’s enemies, who are the bad guys. By that measure, “Charlie Wilson’s War” should do well.

Charlie (Tom Hanks) was a Democratic congressman from Texas and a member of the Defense Appropriations subcommittee in the early 1980s. Roused to righteous fury by Russian slaughter of Afghan civilians, made possible by their command of the air, he arranged through clandestine means and in partnership with the Saudis, Pakistanis and even Israelis to supply the mujahideen, then fighting the Soviets, with shoulder-launched anti-aircraft weapons. From Hollywood’s point of view, the sugar-coating comes in the form of an emphasis on Charlie’s politically unconventional, playboy lifestyle. Commenting to an observer about the unusually large number of well-endowed young women on his office staff, he observes: “You can teach ‘em to type, but you can’t teach ‘em to grow tits.”

This is apparently something that the real-life Charlie really did say. His indulgence in sex and drugs and his profane skepticism about the moral and religious, if not the patriotic pieties of those who elected him produces a lot of the acerbic wit to which Mr Sorkin’s script gives such entertaining play. Told of his appointment to the House Ethics Committee, Charlie comments wryly, “Everybody knows I’m on the other side of that issue.” Yet this ethically-challenged man — along with a lovable, wise-cracking CIA sidekick, (Philip Seymour Hoffman), and a wacky Texas socialite (Julia Roberts), who is also (between rich husbands) a part-time lover — all but single-handedly defeats the Russians in Afghanistan while sticking a thumb in the eye of the boring social conservatives who were supposedly running the country at the time.

Most remarkably, there actually seems to be some truth in this scenario. But if the real-life Charlie Wilson, who served as an adviser to the film-makers, did most of the things attributed to him in the movie, he “wasn’t the only good guy” — as someone who was working in the Pentagon in the 1980s dryly commented to me. No, indeed. Ronald Reagan, for one, was on the same side as Charlie when it came to opposing the Soviets in Afghanistan, though you wouldn’t know it from this picture in which the late president’s name is barely mentioned. Obviously, it makes a better story — again, from Hollywood’s point of view — if Charlie is all alone, a voice crying in the wilderness, and bucking the system all the way until finally by his efforts alone, the mighty Soviet Union cries uncle and retreats, soon to collapse altogether as a result of the defeat inflicted on it by Charlie Wilson.

“Charlie did it,” as no less an authority than the late President Zia ul-Haq of Pakistan put it. Or, in Charlie’s words which end the film: “These things happened. They were glorious, and we changed the world. . . And then we f*****-up the endgame.” The movie offers no further elaboration on this statement, but it seems to refer to the widely held belief that it would have been a relatively simple matter, after the Soviet retreat, for the U.S. to have been so nice to the mujahideen that many of them wouldn’t subsequently have allied themselves with the Taliban and Osama bin Laden. I doubt this myself, but that didn’t prevent me — and it shouldn’t prevent you — from enjoying the movie any more than does its Hollywoodization of political and military processes that in real life are very much more complicated and boring. At least the Americans are the good guys here. And they win. Sort of.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.