Nerd Do-Wells

From The American Spectator“On this New Year’s Day, spare a thought for the hapless nerd,” wrote Rachel Hartigan Shea in The Washington Post on the first day of 2008. She was reviewing a book by a man who was said to believe that “nerds are just about the last group of people it’s safe to mock in polite company.” I don’t see it. On the contrary, nerds — if by that we mean the kind of brainiacs who think that brain-power is all that matters — have inherited the earth. Only in impolite company can nerds be safely mocked — not so surprising, given that nerds and the nerdishly-inclined have replaced more traditional social élites as the arbiters of politesse in our time. Who but a nerd could have come up with the exquisite gradations of social acceptability in the equivalent terms crippled, handicapped, disabled and differently abled? In such polite company the only people whom it is still safe to mock, as the popular and political cultures alike remind us, are stupid people.

A nerd word for nerd is “intellectual” — used unironically to mean a brainy person. Yet for most of its 350 year history in the English language, the word has carried with it a pejorative connotation. Intellectuals are characterized as such not so much by intellect as by a misplaced pride in intellect — a pride which, to more than just dopy anti-nerds, smacks of hubris. It was this pejorative meaning that Paul Johnson intended in his book, Intellectuals, which this year celebrates its 20th anniversary and which did such a brilliant job of adumbrating the swinish personal behavior of a number of celebrated nerds of the last three centuries. By doing so he meant to suggest a causal connection between intellectual pride and swinishness, yet in retrospect all his efforts did little to stem the tide of intellectual pretension or to call into doubt the social status our culture has chosen to confer upon the nerd.

This excessive valuation placed upon intelligence has been an unfortunate thing for our country. It is what allows the Democrats to offer to the American people a foreign and security policy which consists of nothing but being smarter than President Bush. That’s something it’s not difficult to be after the fact. Even President Bush can be smarter than President Bush, once he knows how things come out. Americans used to think other things mattered more than smarts. Courage, for instance. The classic Western High Noon (1952) by Fred Zinnemann made just this point, and if you look at it today it appears almost as an allegory of the Bush administration. Like Gary Cooper’s Marshal Kane, the president is increasingly isolated from and resented by a formerly friendly community which desperately wants to believe that if you are smart enough you don’t have to be brave, and that if you are nice to your enemies they will be nice to you and no longer demand to be confronted.

Even conservatives are too often seduced by the cachet of full-frontal nerdity. Newt Gingrich was the most talented conservative politician of his generation, but he threw it all away for the charms of big thinking — an exchange which, however good it was for him, was less good for his country. The movies nowadays would be on the side of the townspeople of High Noon. Charlie Wilson’s War, Mike Nichols’s amusing version of George Crile’s book of the same name, is characterized by a romanticization of intelligence only less striking than its omission, pointed out by John Fund on another page, of any role for Ronald Reagan in the fall of Soviet Communism. In this movie, Congress, the executive branch and the CIA are mostly clueless, but a shrewd, hard-drinking Democratic congressman, a rich floozy, a rogue CIA man and a few assorted chess-geniuses have the nous to lick the Soviets by supplying Afghan mujahideen with sophisticated anti-aircraft weaponry. Now who would have thought of that?

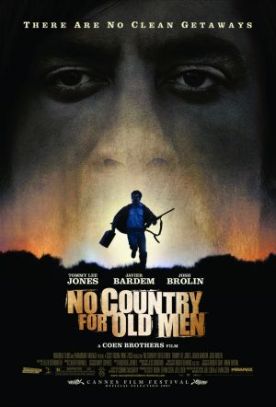

The celebration of nerdishness is more subtle in the recent adaptation by Joel and Ethan Coen of Cormac McCarthy’s novel, No Country for Old Men. This hopeful ascent of the dollar-store Parnassus of the popular culture shows us that wisdom is indistinguishable from despair and the brilliance of art has no other purpose than temporarily to disguise from us the putative meaninglessness of nature. As A.O. Scott put it in raving about it for the New York Times, the Coens’ movie “is purgatory for the squeamish and the easily spooked. For formalists — those moviegoers sent into raptures by tight editing, nimble camera work and faultless sound design — it’s pure heaven.”

Speaking as one of the squeamish and easily spooked, I notice that, like “intellectual”, “formalist” seems to be another word for nerd. The Coens’ hero, a mass murderer called Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), is a nerd’s parody of God: an indestructible, implacable, omniscient and inscrutable force whom his many victims defy to spectacularly little effect. You might as well defy fate itself. Like Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997), now remade in English by Mr Haneke himself and scheduled for a U.S. release in March, the film makes use of the conventions of the filmic art in order to subvert the moral universe that first brought those conventions into existence. “Even a nonbeliever might find it useful to model himself after God,” Chigurh says in the novel to the young woman he imagines he has to kill merely because he promised her now-dead husband, whom he has also killed, that he would do so.

This is a malignant God, who represents the ineluctable force of injustice or evil which would once have been, in the popular entertainments on which this one is parasitic, the ineluctable force of justice or good. Yet the film makes a slight but significant change in the ending of Mr McCarthy’s book. Spoiler alert! In both, the pitiable pleas for mercy of the young woman, played by Kelly Macdonald, are greeted by Chigurh with an invitation to her, which we have seen him issue to others, to call a coin-toss for her life. In the book she loses the toss and is murdered. In the movie, she refuses to call it. “The coin don’t have no say,” she says. “It’s just you.”

“I got here the same way the coin did,” Chigurh says. But then we cut to his exit from the house into the sunlight. This final murder (if that is what it is) of many is not shown. Did he spare the woman after all? Has he made a belated half-concession to the sense of justice and right that has been continually outraged up until now? We may think so, apparently, if we choose — a cruelly mocking consolation exactly like that on offer in Joe Wright’s adaptation of Ian McEwan’s Atonement.

This movie, which also sought the plaudits of the intellectually ambitious over the Christmas season, resembles No Country for Old Men in making a show of respect for our na ve belief that it is unfair and unjust for the heroes to die while really ridiculing that belief. The undeceived, the nerd who knows better, condescendingly offers a crutch to those who are less tough-minded than he. This is the characteristic attitude of the intellectual, a man — for it almost invariably is a man: Mr Johnson’s examples include only the late Lillian Hellman from the distaff side — who disguises his nihilistic faith from the uncomprehending and foolishly believing masses with a veil of fantasy that deceives, and that is meant to deceive, no one.

I would go further and say that fantasy is, if not itself a species of nihilism, then a device with particular appeal to the nihilistic and the intellectually overweening. Such it is, at any rate, in The Golden Compass, Chris Weitz’s adaptation of Philip Pullman’s anti-Christian children’s book. This is another movie that presents us with a morally inverted world in which the bad is good and the good is bad and God is a cruel tyrant deserving of our hatred. Yet the movie has to make certain concessions to youth, beauty and innocence that the more unapologetically nerdish creators of No Country for Old Men and Atonement do not.

All three films, I think, grow out of a belief in the unknowability of truth or reality — the absence of which provides a bit of Lebensraum for nihilistic fantasies of intellectuals which make up in ingenuity what they lack in moral or spiritual coherence. They are representations — meant to be deliberately insulting to our culturally inculcated mimetic expectations — of something we know (and are continually reminded) cannot be real, yet they are the only reality on offer. For the intellectual there is no shame in indulging in such fantasy. The shame would be, rather, in revealing himself to harbor a suspicion that the world is, as all the great artists of the past once supposed it to be, something to be made sense of, rather than something whose senselessness is a mere excuse for them to show-off.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.