Samurai Sage

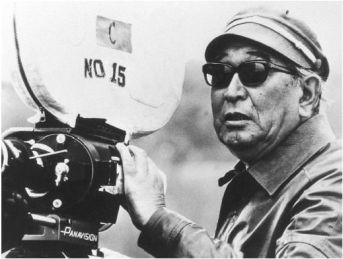

From The AmericanAkira Kurosawa

When Clint Eastwood, an icon of American heroism recognized throughout the world, makes a movie about one of the most storied battles of World War II without either a hero or so much as a glance in the direction of what was being fought for, a movie about war seen only through the eyes of its victims, it is a sign of the cultural times but one that has been a long time coming. Indeed, Mr Eastwood’s victim-heroes in Flags of Our Fathers have become almost as much of a cultural cliché as the idea that only primitive and uneducated people think in terms of wrong and right, black and white, bad guys and good guys. Where do such ideas come from? Most of humankind through most of its history has happily lived in a monochrome world. Why, in the last 50 years or so, has the aesthetic appeal of black-and-white faded? Who taught us the charm and sophistication of grey?

Here’s one candidate: the great Japanese film director, Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998). Of course, he had his precursors, even in the movies. What the French call film noir, for instance, ought properly to be called film gris, since it is founded on the principle of moral ambiguity. There are no heroes, only little men trying to stay alive and out of the way of the thugs who are what heroes, robbed of honor and chivalry and the heroic ethos, have become, or to shake a fist of defiance in the face of the God or fate or economic system that has kept them down. But the noir style hasn’t aged well and still belongs very much to its time and place in mid-century America, as the feebleness of such recent attempts to revive it as Brian De Palma’s Black Dahlia or Allen Coulter’s Hollywoodland remind us. The man who took its essence and made it into a style that could be effectively transmitted to succeeding generations and across national borders had two important qualifications for the job besides his genius: he started out as a painter and from the point of view of a defeated culture.

Obviously, heroic or patriotic war movies such as those that continued being made in Hollywood for another quarter century stopped dead in Japan in 1945, when Kurosawa was making his second film as director. Already, the assurance and visual richness of his style prefigured his accomplishment in film of what the modernist painters had done in Europe and America, which was to make the artist the hero of his work. No longer was artistry meant to be kept out of sight and in the service of its subject. Now the subject was reduced to being an excuse for the artistry. Watching a Kurosawa film is a fatiguing process because there is always so much going on, so many ways the artist has of calling attention to his artistry which always exists on a plane superior to even the most exciting of the stories he has to tell. Moreover, he always adapts his stories to suit his method by giving the pride of place in them to the outsider, the observer of the action that he inserts into the middle of it in order to create the distinctively Kurosawan perspective.

This detached figure is a stand-in for the film-maker and provides the grey in his black-and-white world. His perspective is apparent in Stray Dog (1949), in which a criminal and the detective pursuing him become, in true noir fashion, something close to moral equivalents — as do the revenge-seeker and his victim in The Bad Sleep Well (1960), Kurosawa’s take on Hamlet. The Olympian detachment of the film-maker from the point of view of his characters was the fundamental organizing principle of Rashomon (1950), the film that first brought Kurosawa to the attention of an international audience. There, the same story is told from multiple points of view as a way of illustrating the importance of the observer’s situation — and of the essential Kurosawan datum that there is no “true” or “real” story independent of it. The brilliance of his film-making and its endless geometrical variation, like a kaleidoscope, is the analogue of the point he has to make, putting the story-teller in the position of hero of his own story.

Though skeptical of heroes, Kurosawa always aspired to work on the heroic scale, and the first film in which he was able to do this was The Seven Samurai of 1954. He took as his subject an obvious tale of bad guys and good guys — which it largely remained in The Magnificent Seven, the American remake of 1960 — but he drew back from it to create his characteristic Kurosawan perspective. Partly this was done with extraordinarily subtle camera work, which shifts between telephoto close-ups and deep-focus pans and always manages to pick out of scenes of frenzied action the significant detail. As usual this prominence given to the intelligent observer has as its dramatic analogue the outsider he places in the midst of the action. In this film it is the bumptious ex-farmer and would-be samurai, Kikuchiyo, played by the greatest of all Kurosawa’s stars and collaborators, Toshirô Mifune. The most memorable moment in a film full of memorable moments comes as one of the bandits’ victims, a woman with a baby in her arms, hands the child to tough-guy Kikuchiyo as she dies, and suddenly he breaks down in tears. “The same thing happened to me,” he says. “I was like this baby.”

That life continues in the newly bandit-free village is meant to be seen as being as much a defeat for the samurai as for the bandits whom they so uncomfortably resemble. As they stand watching the villagers’ ceremonial rice-planting at the end, Shichiroji (Daisuke Katô), one of three surviving samurai, says: “I can’t believe we survived again” — whereupon the wise leader of their little band, Kambei (Takashi Shimura) replies that they are also defeated again: “The farmers have won. We have lost.” Kurosawa refuses to allow them — or us — a moment of satisfaction in the heroism or the nobility of their successful if costly defense of the helpless villagers. They were only doing what they were professionally trained to do, which is not significantly different from what the bandits were doing. There’s no nobility among the peasants either. They are cunning and treacherous, even murderous when given the opportunity. But at least they represent life and hope and possibility.

Even as The Seven Samurai was being re-made as The Magnificent Seven, Kurosawa was already at work on the film which would be even more influential in shaping the American movie hero who would succeed the still-chivalrous John Waynes and Gary Coopers who reigned supreme in the 1940s and 1950s. Yojimbo (The Bodyguard) of 1961 had its biggest influence on Hollywood indirectly, through Sergio Leone’s re-make of 1964, A Fistful of Dollars, and its sequels starring Mr Eastwood in the Mifune role as the warrior for hire, selling his skills to the highest bidder in the midst of a gang war. Kurosawa’s original was superior to Leone’s imitation, but in Clint Eastwood the latter had found the sort of charismatic figure who could stand comparison with Toshiro Mifune. Both heroes were meant to be seen as morally compromised characters who, like Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, only emerge as heroes because of a single act of chivalry or idealism that stands out prominently against the background of moral desolation that each inhabits.

These are among the first “cool” heroes. Cool is defined by self-containedness and individuality, the ability to be sufficient unto oneself. The cool heroes are by nature loners like the ronin, or independent samurai, or, in American movies, the private eye. Kurosawa’s cool heroes owe a lot to Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe, who also operated against a background of vice, criminal violence and treachery but somehow managed to stand just enough apart from it to retain a solitary, quixotic kind of heroism. These were heroes who didn’t look heroic. They weren’t better than other men — apart, perhaps, from being quicker on the draw or faster and more effective at wielding the samurai blade. They certified their common humanity even as they stood apart from the particularly contemptible version of it that they saw around them. This was why Kurosawa kept coming back to the period of the breakdown of central authority and warlord rule in the 16th century, both in the black-and-white samurai films and in the later technicolor epics, Kagemusha (1980) — co-produced by Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas — and Ran (1985).

Against the background of visual splendor provided by the sumptuous sets and the color-contrasted armies in these films, the little man who acts as observer, victim and commentator — the peasant double (Tatsuya Nakadai) in Kagemusha or the fool or jester (Peter) in Ran — stands out all the more prominently. He forms the characteristic Kurosawan triangle. In The Seven Samurai, this triangle is formed by the peasants, the bandits and the samurai, with Kikuchiyo — half-peasant, half-samurai — moving between the sides. In Yojimbo, it arises out of the opposition between the Seibei and the Ushitora factions on two sides and Sanjuro, the lone samurai all on his own or with the tavern-keeper, Gonji (Eijirô Tono), moving between the two on the third. In The Hidden Fortress (1958), later to be so influential on George Lucas in the creation of the first Star Wars movie, the perspective on the struggle of the forlorn remains of the Akizuki clan — the Princess Yuki (Misa Uehara) and her loyal General Rokurota Makabe (Mr Mifune again) — to escape their persecutors of the Yamana clan is provided by the two comic grotesques, Tohei (Minoru Chiaki) and Matakishi (Kamatari Fujiwara), the cinematic ancestors of R2D2 and C3PO.

In Rashomon, there are two triangles: that of the priest, the commoner and the woodsman as they tell the tale and that of the bandit, the samurai and the lady in the tale that is told in three (or four) different ways. Here, even more than in the later color epics, we can see how Kurosawa constantly re-echoes these triangular relationships in the composition of his shots, as if he felt it necessary constantly to remind us that we are not to allow ourselves the luxury of self-identification with one side or the other, as in the old heroic paradigm, but only with the detached and non-committal third or “grey” option. Even in Rhapsody in August, a late film in which he meditates on the moral significance of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Kurosawa refuses to take sides. Like the old widow, perhaps, he is only prepared to say that war itself is responsible for the tragedy of so many tragic deaths — which is essentially what he is saying in the conclusion of The Seven Samurai.

But this is really a denial of responsibility. Responsibility is also binary: either you’re innocent or guilty, a good guy or a bad guy. Kurosawa always insists on carving out the third option for himself in the triangulating position of the observer, the watcher — the painter that he started out to be or the film-maker that he became — or the unreliable witness who was the figure at the heart of Rashomon. This person doesn’t take any responsibility because there is no longer any responsibility to take. The truth is unknowable. It only exists in the versions of it that all of us make up to excuse and justify ourselves for the things that we do. Similarly, the moral world is always like that of the cursed town in Yojimbo, with two equally unpalatable enemies killing each other and humanity somewhere in between trying to survive and, where possible, perform the one act of kindness — like the woodsman’s adoption of the abandoned baby in Rashomon — that can redeem human nature. It’s a compelling vision. So compelling that Hollywood has been completely captivated by it. And if it leaves no room for the old-fashioned hero, do we care? Perhaps not. At least until we once again stand in need of heroes.

This is a somewhat expanded and altered version of an article that appeared in

The American of November-December, 2007

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.