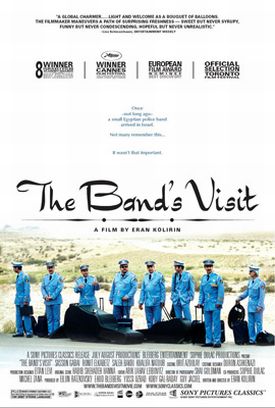

Band’s Visit, The

What I liked best about The Band’s Visit (Bikur Ha-Tizmoret) by the Israeli director Eran Kolirin was the face of its principal male character, the leader — as he frequently reminds people — of the Alexandria (Egypt) Police Ceremonial Orchestra. His name is Lieutenant-colonel Tewfiq Zacharya (Sasson Gabai), and his face expresses immense dignity and sadness. He is a man who seems to embody defeat without ever being, quite, defeated. The latest disaster in his life is that, having arrived in Israel with his eight fellow bandsmen — all of them dressed in striking powder-blue uniforms that make them stand out against the Israeli desert landscape like a crocus on an iceberg — to play at the opening of an Arab Cultural Center, he has taken the wrong bus to an isolated desert village where, as one of the locals informs him, “there is no Arab culture, no Israeli culture, no culture at all.”

His informant is the well-lived-in but still very sexy Dina (Ronit Elkabetz). She runs a small restaurant and, in the absence of any more buses that day, or any hotels in the vicinity, she organizes the band’s lodging for the night by appealing to her neighbors. Tewfiq and the youngest band member, Khaled (Saleh Bakri), she invites to stay in her own small apartment. And that’s about it, really. Besides Tewfiq and Khaled, only Simon (Khalifa Natour) among the other bandsmen stands out as an individual. He is a frustrated composer and Tewfiq’s prospective successor as director of the band and, with one or two others, he is quartered with a dysfunctional Israeli family whose interactions around the dinner table he watches with a certain bemusement.

But it is mainly Tewfiq, Dina and Khaled who command our attention. Tewfiq is a man who has lived all his life according to the two pillars of certainty of his existence: a belief in traditional Arab music and a belief in authority — his own and that of others. His is now being undermined in different ways by Khaled and Simon as well as those in authority back in Egypt who want to cut back or eliminate the funding for the band. He can do little or nothing about any of this. He has only music left, and maybe not even that much longer, for he recognizes that its importance in his own life is not reflected in the lives of others. And not only does the philistinism of those in authority over him seem harder and harder for him to resist, the heart has gone out of him as a result of a ghastly personal tragedy that he eventually reveals to Dina.

Dina also obligingly serves as a spokesman for the philistines too. Why do the Alexandria police need their own band to play traditional Arab music, she asks him.

“This is like asking why does a man need a soul,” says Tewfiq.

The film has many funny as well as touching moments, most of them occurring when Khaled tags along with a shy young Israeli named Papi (Shlomi Avraham) who is going on a double date with a much more confident and attractive friend to a roller-skating rink. The friend soon disappears with his girlfriend, leaving a hopelessly maladroit Papi to make his usual mess of getting to know her cousin, Julia (Rinat Matatov). He confesses to Khaled, who is good-looking and a natural ladies’ man, that whenever he tries to talk to a girl “I hear the sea in my ears.” Khaled patiently instructs him in what to do as he sits next to Julia and Khaled sits next to him, demonstrating each move he suggests on Papi himself before Papi tries it on Julia.

Mr Kolirin takes it as a given that there can be no permanent connection between these Israelis and these Arabs. Though the only direct reference to the past wars between Israelis and Egyptians comes in Dina’s restaurant when one of the bandsmen hangs his hat over a photograph of an Israeli warplane in action, there is no overt reference to politics at all but an understated sense that the villagers and the bandsmen live and always will live in different worlds, which makes their moment of contact all the more special, even though nothing important or permanent comes of it. It is rather a moment of enlargement and understanding whose mental, emotional and spiritual effects may be more lingering than anyone can foresee, at least from the point that the film takes us to.

It ends a brief shot of the band’s performance, when it has finally got to where it is supposed to be, and a line from the lyric of the song they play sticks in the mind. “Under eternal sun our forgotten days are gathered.” The idea of “forgotten days” is also reflected in the movie’s tag line: “Once, not long ago, a small Egyptian police band arrived in Israel. Not many remember this. . . It wasn’t that important.” And yet we are meant instinctively to feel how important the day really has been in the lives of Egyptian bandsmen and Israeli villagers alike, whom unimportant things bring, briefly, together.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.