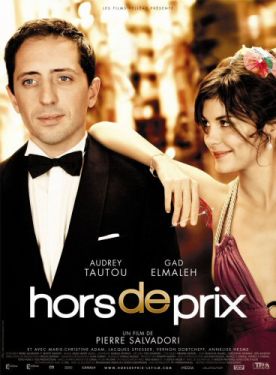

Priceless (Hors de Prix)

Pierre Salvadori’s Priceless (Hors de Prix) begins by introducing us to a man who can’t say no. Though perhaps not so interesting as a woman who can’t say no, this man also has his charms. He is Jean Simon (Gad Elmaleh of The Valet), a waiter-cum-bartender- cum-dog-walker at a luxury hotel in Biarritz who is mistaken by a gold-digging minx called Ir ne (Audrey Tautou) for a rich playboy and decides to live up to the part — less, it seems, because he sees an opportunity to get Ir ne into bed than because he instantly and irrevocably decides that it has become his purpose in life to be whatever she wants him to be. Thus, when she discovers that he is only a waiter, it infuriates her but makes no difference to at all him. He allows her to bankrupt him in an afternoon. For her this is revenge for spoiling her prospective match with Jacques (Vernon Dobtcheff), a rich older man, but for him it is simply playing the role that she has asked him to take on. He is hopelessly and irrevocably in love.

There is a lovely moment after Ir ne has spent all Jean’s money and is about to leave him flat. He holds up what we are obviously meant to see as his last Euro and asks her for ten more seconds — which he then spends just looking at her with adoration. Nonplused, she takes the coin from his hand. “Time’s up,” she says, and walks away. But he is unfazed; she is rattled.

That he should be a fool for love, as so many people are, is no surprise, but for Jean there is more to it than that. As a waiter, of course, it is his job to please those who are richer and more socially dominant than he, and he has seemingly learned to truckle to them obligingly. He walks their dogs along the luxury hotel’s beachfront at Biarritz, and he also obeys when a rich man orders him to sit down and have a cigar and a brandy, even though he is on duty at the bar and not supposed to leave his post. This is what gets him into trouble after he falls asleep and is found in an unwaiterly posture by Ir ne, whose Jacques has also passed out from drink. But Mr Salvadori and his co-screenwriter, Benoît Graffin, mean to put the case to us: what if this man is not, as he seems, simply servile, trying to make his own way by sucking up to the rich. What if he is that rarest of innocents, a servant who does not serve to live but who lives to serve?

So strikingly unusual is this idea as a dramatic mise en sc ne in the 21st century that it seems to have gone right over the heads of some critics. Stephen Holden of the New York Times, for instance, calls this a “cynical Gallic comedy.” I am at a loss to explain such a bizarre judgment unless it is Mr Holden’s way of saying that he thinks M. Salvadori’s utterly uncynical ending in which — spoiler alert! — true love triumphs over cynical self-interest is meant as a nudge and a wink to the audience. It is too fantastical, in other words, to be anything but an ironic, post-modern affirmation that it is not love but the glorified prostitution of its heroes earlier in the film which is really the way of the world after all. But he also calls the film “an amusing ball of fluff that refuses to judge its characters’ amoral high jinks,” which is simply untrue. I think maybe his moral ear is just not quite finely tuned enough to catch the unmistakable note of judgment in the tradition of French comedy. He thinks that morality must be moralistic.

There is no moralism in Priceless, but there certainly is morality. Jean is saved from ruin when he, too, becomes the sexual plaything of a rich older woman, Madeleine (Marie-Christine Adam). There is a fierce triumph for Ir ne in being able to say to Jean: “We’re the same now.” Except that they are not. The irony in her words is that, without yet realizing it, Ir ne is becoming more like him, not he like her. She instructs him in the arts of seduction, and how to simper and pout in order to take his rich benefactress for all he can get out of her. But Jean is not really interested in enriching himself. Madeleine is to him just another opportunity to serve, like some courtly lover of old, his own true lady-love. So when Ir ne sees an opportunity to reclaim her original sugar-daddy, Jacques, Jean unhesitatingly gives up Madeleine and all her promised riches in order to assist her.

Gradually, we are meant to see, the example of Jean’s unselfish devotion has its effect on her until, before she knows it, she has allowed herself to be taught by his example to choose love over cynicism and self-interest. In Mr Holden’s view, presumably, such a choice could not be made otherwise than (as he says it is here) “unrealistically,” and hints of fantasy and fairy tale could easily have crowded out the serious moral lesson were it not for the immense presence of Mlle Tautou. There’s nothing of the fairy-tale princess about her. She is, rather, as sublimely sexy and therefore impressively real as any of the great screen goddesses of old. That Jean — or any man — would give up everything and live henceforth only to serve her is completely believable. This is what grounds the film and prevents it, in my view, from being merely ironical. Believability is contagious and spreads to parts of the film that might otherwise be harder to credit.

At one point Ir ne has to explain to Jean that “Charm beats good looks every time.” She, of course, has both but, as in her earlier film, Amélie, her charm turns what could have been a tedious po-mo fable into a love story that is almost magical.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.