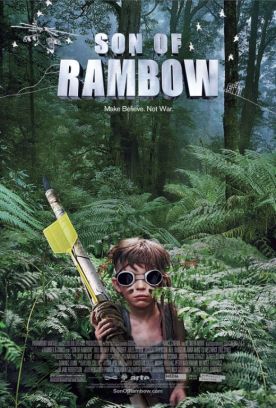

Son of Rambow

Psychologists tell us that geese undergo a process known as “imprinting” which attaches them to their mother for long enough to learn from her how to be a goose. At a certain point in their infancy, they will “imprint” on the first thing they see. As this is nearly always mother goose, this works out well for your average goose. But if by some chance mama is away and a dog or a fire engine happens along at the crucial moment, the gosling will grow up thinking it is a dog or a fire engine instead of a goose. Set in Britain in1982, Son of Rambow by Garth Jennings (The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) shows us what might be considered a human instance of imprinting. Eleven-year-old Will Proudfoot (Bill Milner) is a member of a sect called the Exclusive Brethren, who are forbidden to watch movies or TV — among many other things they are forbidden to do. His father is dead, and when he accidentally catches a snippet of a pirated copy of First Blood on the television of his first non-Brethren friend, he thereafter regards John Rambo as his father.

As it happens, the friend, Lee Carter (Will Poulter), is making a movie of his own with the videocam he uses to make pirate copies of Hollywood films. He hopes to win a prize offered by a television program for young film-makers. Will swiftly takes the project over, turning it into a Stallone knock-off called Son of Rambow (because he doesn’t know how the name is spelled) with himself in the role of the son. Really, of course, it’s the movies that Will has fallen in love with and the forbidden fantasies that they give rise to. To this very slight extent, therefore, Mr Jennings’s movie surprisingly allows us a glimpse into what it is that might lead rational people to forbid their children to watch movies and even, perhaps, into why and how movies can be bad for us, too. Even those of us who love the movies ought to be reminded of that once in a while.

But any such serious purpose, if it was ever more than an accident in the first place, is soon forgotten as Mr Jennings allows himself to get caught up in exploring the friendship between the two boys, the tensions within Will’s family, and between them and their church, which are occasioned by it, and by the sheer comedy of the boys’ movie-making. There is an elaborate sub-plot involving the coming to town of a group of French exchange students, including the impossibly cool Didier (Jules Sitruk) who strikes the school like a thunderbolt. As all the other kids defer to him, he defers to the hitherto unknown Will because he wants to be in his movie. This drives a wedge between Will and Lee Carter with more or less predictable consequences.

It doesn’t do much for the movie, however, and in spite of many funny and enjoyable scenes, it begins to stray farther and farther from plausibility or realism as it goes on. Where it really didn’t ring true to me was in the end when the finished cut of Son of Rambow is shown and both boys apparently find it as screamingly funny as we are obviously supposed to find it. This presupposes that they knew all along that they were making a funny movie and not an action adventure flick like First Blood. Now we know as well as Mr Jennings does that First Blood, like other movies featuring cartoon heroes, is itself laughable, but the kids don’t know that. If they had known it, they would never have wanted to make their own version of it in the first place. The impulse to parody comes along later much later in life than age 11.

Then, it is sober earnest heroism — or what, like First Blood, can pass for it in a dim light — that appeals to children. The film itself makes it clear that this is what makes Will want to make the movie in the first place. The part of First Blood that we see along with him is the part where Richard Crenna warns that 200 men won’t be nearly enough to catch the amazing, the super-human John Rambo. “You’d better make sure you’ve got plenty of body bags,” he says, or words to that effect. At this point we cut to Will, watching from hiding, as his eyes widen: “Two hundred men!” he says wonderingly. It is precisely the cartoon quality of the movie’s heroism that attracts him: not because it is a cartoon but because, to him, it isn’t.

One of the picture’s virtues, in fact, is that it shows nicely how Will, before he meets Lee, is perfectly adapted to life as an outsider, living very much in a fantasy world with his drawings and his little secret treasures in the shed behind his house or the back row of the classroom where no one takes any notice of him. Rambo simply gives a new direction to his already rich fantasy life. How much better the movie would have been if we could have been allowed to see, however distantly and imperfectly, the down-side of this gap between real life and the fantastical and therefore the sense in which Will’s mother (Jessica Stevenson) is right about the movies. At least in some sense it is for his own good that he should be spared the meretricious charms of the popular culture.

Instead, mom is the one who is converted to his view — and Mr Jennings’s and yours and mine and the whole wide world’s for that matter. This is the view that pop cultural trash is, if not to be loved in every instance, at least to be preferred to a cloistered virtue. We may even agree that it is better not to protect children from such trash, just as it is better not to isolate yourself in an exclusive community that looks down on “outsiders.” But that doesn’t mean that those who are so isolated do not have a point about the artistic junk food that we all consume so eagerly. It is not merely irrational or foolish in them to seek to protect themselves and their children from the spiritual and intellectual degradation that so much of popular culture rejoices in. A bit of an effort to see why they do it, and the real dangers to which they are reacting would have made what is in any case an enjoyable film a truly great one.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.