The Shock is Over

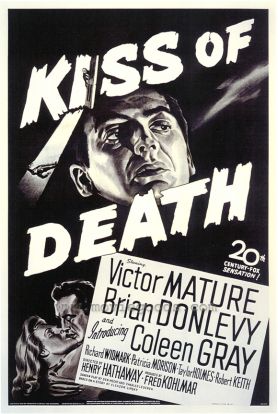

From The American SpectatorHe was one of those people the news of whose death makes you say to yourself: “I thought he was dead.” Well now, aged 93, he finally is. But Richard Widmark will live on for generations to come if only as Tommy Udo, the ferret-like gangster in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947) who tied Mildred Dunnock into her wheelchair with a lamp cord and pushed her down the stairs because she wouldn’t rat out her son, a stoolie. That moment made the sort of impression on post-war American audiences that Mickey Spillane’s hero Mike Hammer did in I, the Jury, first published in the same year, when he shot a woman in an act of revenge. Spillane writes of the incident with relish, as his hero points his gun: “‘How c-could you?’ she gasped.

“I only had a moment before talking to a corpse, but I got it in. ‘It was easy,’ I said.”

|

There is an unmistakable enjoyment in that line, just like Richard Widmark’s when he giggles as he pushes the old lady down the stairs. One of these tough guys was supposed to be good and the other bad, but ideas of good and bad suddenly seemed to matter less now than their no-nonsense toughness and the more-or-less equivalent ruthlessness of their methods. That was what seemed new and exciting. Mike Hammer’s “It was easy,” was meant to tell us, as well as his victim, that it was no use for her to try to shame him by an appeal to outdated notions of chivalry towards “the weaker sex.” He cared as little for her femininity and vulnerability as Tommy Udo did for that of the woman in the wheelchair. Gallantry was now to be regarded as a dead letter for heroes and villains alike.

And that, I imagine, must have been rather a thrilling, even a liberating thing for a lot of people to hear after a war in which so many millions of civilians had died. This lack of sentimentality or delicacy seemed more real, more true-to-life than what had by then come to seem the pretenses of gentlemanliness. The film’s tag-line — “It will mark you for life. . .” — for once turned out to be approximately right because of this scene. It had to have been the reason why Widmark in his first screen role was nominated for the Oscar that year as best supporting actor. “The sadism of that character,” wrote David Thomson in The Biographical Dictionary of Film, “the fearful laugh, the skull showing through drawn skin, and the surely conscious evocation of a concentration-camp degenerate established Widmark as the most frightening person on the screen.”

Yes! That’s what people now expected a villain to be. No more of that pre-war, phony-baloney, high-minded pretense of honor that such post-war tough guys tore through like bullets through soft flesh. The movies were also inviting people in to an exclusive club: the club of the undeceived. They flattered us by playing upon one of the conventions that had been central to the popularity of movies from their beginnings, which was the assumption that shock, fear and horror are the tokens of reality. Like the train in the Lumiere brothers’ film L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1895) or the bandit firing his gun at the camera in Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903), the signature trick of the film-maker from the beginning was to give the viewer a stab of fright that something was coming off the screen and straight at him. But such pleasing shocks are also wasting assets. Once the trick has been performed, it loses some of its power to shock. We have to seek new and heavier doses of frightful or horrifying sights in order to produce the same rush.

Thus the power to horrify of Richard Widmark — who in Kiss of Death at least had a motive to kill besides his own enjoyment of killing — had so far waned by the 1990s that his equivalents had become the psycho serial-killers of The Silence of the Lambs (1991) or American Psycho (2000), men who had no human existence apart from their pathological love of killing. At first, back in Widmark’s day, it must have seemed that his kind of lurid villainy was more real than the nuanced kind, or the kind where the bad guy is also shown to possess a rudimentary conscience or sense of dignity, an unwillingness to be more violent than he has to be. But as time wears on, we seem to have come to value the same or similar kinds of theatrical wickedness because of their unreality. Nobody can suppose that Hannibal Lecter is more real, in the sense of being true-to-life, than other sorts of killers. We just like him because he is so over-the-top with his villainy.

The reason why may be suggested by “The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the Moving Image,” an exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington this spring. In Part I, “Dreams” (closing May 11; Part II: Realisms” opens on June 19), one of the exhibits consists of a film loop by Christoph Girardet of the “iconic moment” in King Kong (1933) when Fay Wray, helpless and spread-eagled, struggles and screams at the camera to give us a powerful sense of the unutterable horror of the giant ape — which she is presumably looking at but which we cannot see at this point. The moment is drawn out, the screams prolonged in such a way as to suggest a disturbingly misogynistic, even Mickey Spillane-like enjoyment of this now endless moment of fear and horror at a now-dead actress’s long-ago sense of her own helplessness and vulnerability. And yet there are unlikely to be many complaints about this. It’s still only a movie, after all, and part of what we are enjoying when we enjoy it is our sense of superiority to those people who, three quarters of a century ago, may be supposed to have been actually frightened by it.

In other words, by a curious sort of paradox, what begins by impressing us with its realism ends by endearing itself to us by its fakery. We loved Richard Widmark’s Tommy Udo because he seemed real, but we love Anthony Hopkins’s Hannibal Lecter because he seems unreal. Or rather, the realism has become so heightened that the fright it conveys and our sense of our own superiority to it come almost simultaneously. Nobody wants to be marked for life anymore, only for as long as it takes to make cannibalism into a joke. We have seen through the imposture and so not only have occasion to congratulate ourselves at our own sagacity in doing so but also endlessly to enjoy ourselves enjoying our — or, like Mr Girardet, our ancestors’ — initial shock. We cherish the movies as we cherish our own memories, nostalgically, because in part they are our memories. They reassure us that reality is really all about us.

The extent to which the movies are now an essentially narcissistic medium is really the theme of the Hirshhorn exhibition. Another of its exhibits, called “Trailer” by Saskia Olde Wolbers, ends with a reference to “the meaninglessness of being unobserved..” I couldn’t tell quite what was being said about the meaninglessness of being unobserved, since Ms Wolbers’s little film was mostly incomprehensible both in the sense that it was obscure and that it was often inaudible. It was also doomed itself to be pretty largely unobserved, I thought, for this reason. But the phrase is a helpful summing up of what the exhibition shows us, and what it prominently displays in a quotation from Stephen Fry’s Making History to the effect that we are all movie stars now in every waking moment of our lives. Congratulations! “We have no need of entering a movie theater to experience cinema,” claims the exhibition’s brochure; “life itself is just like a movie.”

Or at least if it isn’t, we’re doing all we can to make it like one. The great collaborative effort of YouTube is thus, perhaps, the latter-day equivalent of the medieval cathedrals of Europe: a communal work of art and craftsmanship that is also an expression of the spirit of an age. It is an age which begins with the ersatz tragedy of Arthur Miller’s Willie Loman in Death of A Salesman (1949) and his wife’s unhinged and nonsensical insistence that “Attention must be paid!” Who says it must? Who decided that imposing upon one’s neighbors the psychodrama of one’s life had suddenly become a human right? But now it’s pretty much accepted as one. And perhaps the age will end with a new service I heard about on the radio only this morning, a service that for $1500 will allow you to pretend you are a celebrity for a day, complete with your own limousine, entourage and trailing gang of fake paparazzi. At last! Now no one need any longer suffer from the meaninglessness of being unobserved.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.