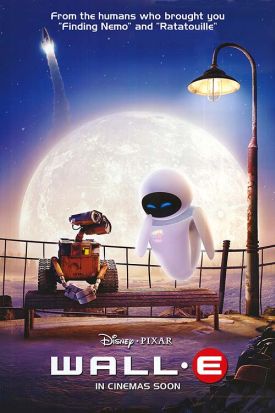

Wall-E

Pixar’s Wall-E, directed and co-written by Andrew Stanton (A Bug’s Life, Finding Nemo) is an environmentalist parable which borrows liberally from the portentousness futurism of 2001: A Space Odyssey and various post-apocalyptic yarns of yesteryear such as Planet of the Apes and Soylent Green. Like them, too, the movie looks upon the adventures of the human race in a post-terrestrial world as if its authors were not part of it, as if they were telling the story of some other planet and some other species — a breed of “consumerist” beings who can only buy stuff and consume stuff and throw stuff away and get fat. People, in short, are disgusting. Machines are all right. Animals are all right, though the only one left appears to be a solitary cockroach. Likewise plants, though there’s only one of those too. Otherwise the earth is deserted, save for the mountains of human detritus, now some eight centuries old.

Of course, misanthropy is common both to post-modernism and environmentalism, so there should be no surprise in the fact that Wall-E looks upon the human race with such condescension. The people of the movie, all that remain of earth’s population, tour the universe endlessly on an immense cruise liner, all their needs attended to by electronic servants. How and why they have managed to keep reproducing while lounger-bound is a mystery. They say that fat people are up in arms about the film’s depiction of humankind of the future as dirigible-shaped couch-potatoes so accustomed to their hover-loungers and electronic entertainments that they have all but ceased to be ambulatory, but the insult is to all of us. Or all except for the nerds by whom and for whom this film was made, who presumably find it more natural to identify themselves with a machine than with their fellow organic life forms.

The machine is the eponymous Wall-E, an anthropoid trash-compactor. He and his sidekick, the mercifully unspeaking cockroach, are the only animate beings, organic or inorganic, left to keep company with earth’s derelict buildings and the mountains of trash that Wall-E has piled up. Wall-E, which stands for Waste Allocation Load Lifter — Earth Class — is repeatedly shown trembling with fear at the approach of frequent dust storms or the thunderous arrival of the space probe that brings a new robot, EVE (Extra-Terrestrial Vegetation Evaluator), to see if any vegetation is yet capable of growing on the poisoned planet. Wall-E also trembles at the approach of the sleek, egg-like Eve, but for a different reason. Does it, then, have a central nervous system? This would be rather excessive circuitry, as it might seem, for a piece of metal designed to squash trash into cubes and pile them up. But of course you will see that I am being disingenuous. It is instantly apparent that Wall-E lives in an animist world, like the Germanic tribes who dreamed up a similarly solitary hero like Siegfried, who could talk to the birds.

As always, animist assumptions land us in philosophical and spiritual difficulties, or at least they would do if it weren’t for the exemption claimed by the silliness of both post-modernism and environmentalism from being measured by ordinary yardsticks. The film is set sometime after the year 2775, which is the year in which the current Captain (Jeff Garlin) assumed command of the space cruise ship Axiom, on which what remains of the human race at that date resides. As the crew and passengers are said to be approaching their 700th anniversary on the space ship, this means that they must have left earth only a few decades from now, at a time when Earth is said to have become uninhabitable. It is also said that no probe seeking organic life on Earth has ever returned with a positive result before, which means that all organic life must have been eradicated from the earth before the end of the present century.

Not even the extreme environmental alarmists are predicting that organic life — which may be ornery but still seems pretty tenacious as of even date — will give up the struggle so easily. Also, in 700 years, I think there would be much less remaining of the signs of human habitation on a deserted earth than we are shown in the movie, where the relatively fresh look of the trash that the title character collects suggests that the human race decamped only a week or two ago. Is it possible that a Zippo lighter more than 700 years old could still be so charged with lighter fluid that it fires up at the first spin of its still-spinning little wheel? Wall-E puts himself to sleep at night by watching an ancient VHS cassette of Hello, Dolly! But if it makes sense that a trash collector, even a robotic one, should become a nostalgist — and being nostalgic for Dolly! is being nostalgic for nostalgia — what are all those porcine couch-dwellers, our multi-great grandchildren, watching in their electronic cocoons light-years away from their ancestral planet? We are not told.

The good thing about Wall-E is that an incipient revolt by the Axiom’s on-board computers, deliberately meant to call to mind that of 2001: A Space Odyssey, inspires the human beings to struggle to their tiny little feet and waddle back to a newly-reinhabitable earth. A machine may be our savior, but at least we are saved — and saved, in part, by romance. This is not only the odd-couple romance of Wall-E as messy Oscar and the gleaming Eve, like the rest of her kind from the spaceship, as endlessly fussy Felix, nor the happy memory of musical comedy attributed to a lonely robot picking up trash on a deserted planet. For that is itself the old romance of Robinson Crusoe, and of the utopian dream of beginning the world over again. The dream must be a familiar one to nerds with megalomaniacal tendencies. Now, to judge by Wall-E and its success, it is becoming a dream for all mankind.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.