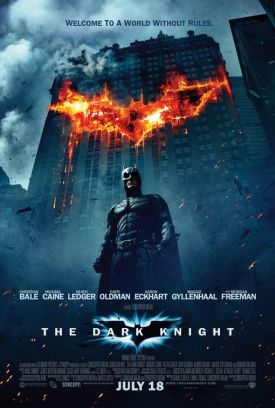

Dark Knight, The

Quentin Tarantino, I hear, is making a new movie. Its provisional title is Inglorious Bastards, and it deals with some American Jewish special forces troops, led by Brad Pitt, during World War II who go on a personal revenge mission against the Nazis and f*** them up! The point, as with all Tarantino movies, is to celebrate (a) inventive and picturesque (in contemporary movie terms) ways of killing or injuring people, like having their brains knocked out with baseball bats and (b) the cartoon villain-heroes or hero-villains who engage in them. As Roger Boyes, reporting for The Times of London, wrote,

it is not just the scalping, or the carving of swastikas in foreheads, or the shooting of a German officer’s testicles, or the slow strangling scene — all shown with Tarantino’s customary love of detail — that is likely to upset the [German] nation and its critics. It is the whole idea of turning the Second World war into a kind of comic book adventure in which not a single German character has redeeming value.

You’d think — wouldn’t you? — that there would be enough real evil and to spare in the historical Third Reich to fuel yet another World War II melodrama, but it turns out not. Real evil — or rather, since “real evil” in Augustinian terms is an oxymoron, evil as we experience it in the non-cinematic world — just doesn’t cut it in Hollywood anymore.

It’s not just Nazis. Any time the movies try to represent evil, it must be as a grotesque caricature, deliberately exaggerated in order to make what would otherwise be something scary into something funny. Or something both scary and funny. In other words, evil has become post-modernized. Thirty or forty years ago, the vogue for psychoanalysis required that you give some explanation, some accounting for a movie villain’s behavior. The great example was Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) which appealed to its era’s suspicion of “momism” by accounting for the evil of personable young Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) with the mother of all mother-fixations. It may not have been all that persuasive as psychoanalysis, but it played a necessary role in the making of that movie: the provision of “motivation.” The public demanded at least that much in the way of a rational accounting for what they saw, and there was something excitingly progressive in the psychological account — as opposed to such an old fashioned kind of motivator as, say, having Norman catch a glimpse of the $40,000. That was the point of having him pitch the money unnoticed, still wrapped in the newspaper, into the trunk of the car along with Janet Leigh’s body. The audience was forewarned that the motivation, when it was finally revealed, would be an outlandish, even an unimaginable one.

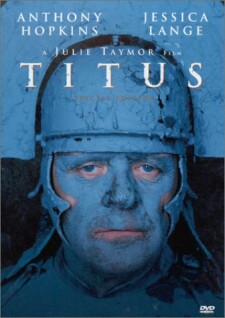

You might even say that the motivation was the real hero of the movie. But the elevation of the outlandish and unimaginable to a starring role ultimately ended in the death of motivation itself. Today’s evil icon is not Norman Bates but Hannibal Lecter: the psycho who is not a psycho for any reason, except for the reason that he just loves being a psycho. As a result, evil becomes a sort of fashion statement. It doesn’t really count as evil if there is a motive or an explanation for it. It must be evil for evil’s sake. There is no better example of this than the new Batman movie, The Dark Knight, currently setting box office records, partly because — I believe — of just this transformation of human evil into something glamorous, something with the power to seduce even the best of us. Partly, too, it’s because Heath Ledger, the actor whose performance now bids fair to supersede even Anthony Hopkins’s Hannibal as the iconic example of that glamorous figure, the serial killer, died shortly after filming of the movie was completed and, as more than one critic has suggested, the insomnia and depression for which he took an accidental overdose may have been caused by the disturbing nature of the role of the Joker.

He is described in the movie as one of those who “just want to watch the world burn.” Are there such men? Conceivably. But history affords no example of them, outside of comic books and the movies, attaining the sort of power it would take actually to burn the world, or even any very significant part of it. Reality seems to provide a natural check upon such people in the form of a shortage of those who both (a) share their psychosis and (b) are willing to play the part of humble assistant — rather than starring as the evil genius themselves — in accomplishing their purposes. This problem for the would-be evil geniuses — a reassurance to the rest of us — is what creates the distinctive unreality of Mr Nolan’s movie. Again and again we see Mr Ledger’s Joker pulling off the most fantastically-conceived acts of evil which, in real life, would require a virtual army of assistants, many of whom would have to be almost as clever as he is. Yet the movie shows us not even one. We do see the Joker lording it over some fellow criminals on a couple of occasions — not the best way to gain their cooperation, one might have thought. And, in the bank robbery with which the film opens, he casually murders all his assistants, which is even less likely to help him with any hypothetical recruitment effort. So how does he do it?

Ah! That is of course the question that must not be asked if the movie is not to drown — as I believe it does drown — in its own preposterousness. This, we are to understand, is strictly a comic book movie, a movie whose action isn’t supposed to look like reality but only like the childish fantasy of a comic book world in which anything can happen. All the Joker’s tricks occur as if by magic — they are, like the evil deeds of the villainous hero of No Country for Old Men, inverted miracles — because, in the comic book world of the serial killer, not only have we dispensed with motivation, we have also dispensed with other sorts of explanation. It would be very vulgar and uncool of the comic book audience to ask — as the audience of those old-fashioned policiers and detective stories used to ask — to see how the trick was done: how the crime was committed or how the criminal was caught. That went out with “Dragnet.” This must be why, so far as I know, no critic among the many who have so lavishly praised The Dark Knight has so far had the bad taste to cite its wild implausibilities even as flaws in Mr Nolan’s masterpiece, let alone fatal ones.

But I think that the movie pays a terrible price for its exploitation of comic book conventions in order to give itself this peculiar, unworldly appearance. For when the movie attempts to turn serious and make the transition from fantasy-land back to reality in order to proclaim a moral, I find it impossible to take it seriously. Of course it doesn’t help that the moral is such a feeble and familiar one — in fact, a comic-book moral to go along with the rest of the comic-book trappings — namely, yet another iteration of that favorite Hollywood trope about how the hero and the villain are really just two sides of the same coin. Only the fact that intelligent people still, unaccountably in my view, regard this as a profundity can account for either the critical reception or the box office success of the movie. Those wishing to read more about my critique of this notion as a moral or political judgment are welcome to consult my review of David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence, but here I’d only like to point out that anyone who finds it unbelievable when exemplified in a relatively real-looking scenario can hardly be expected to find it any more persuasive when the hero and villain are two such comic-book grotesques as Batman and the Joker.

Of course, the movie’s admirers won’t mind the comic book trappings, and that is their right, but even they must see that its attempts at seriousness are that much less serious for them. If everything else in the movie is unreal and belongs to the comic book world, how can we believe that the moral alone belongs to the real world? And such a moral! I have heard the convergence of Batman and the Joker compared to that between John Wayne and Lee Marvin in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. But Ford was telling us that people want to believe heroism grows out of reason and law and civilization but that it really doesn’t. Instead, it is a throwback to the most primitive honor cultures before there were any law or civilization, which are things that cannot be contracted for. The Dark Knight tells us the opposite: that both heroism and villainy grow out of reason and law and civilization and that, therefore, these things are mere shams and subterfuges masking a Hobbesian reality devoid even of honor, in which man is a wolf to man and there is nothing to believe in but the individual Nietzschean will, either to good or evil. It’s the sort of thing that you have to be an emotional adolescent, steeped in his own anti-social fantasies, in order to believe.

I have also heard the superhero movie in general and Batman in particular compared to the Homeric epics, because they deal with larger than life figures and even immortals. But the reality of the Homeric epic is conveyed by the fact that those who are its heroes do die — and that the tragedy of their deaths is played out against the backdrop of the comic soap opera of the immortal gods. The Dark Knight once again puts things the other way around. It’s the heroes who are the immortals. Not only Batman himself but those who apparently “die,” including the Joker and the other supervillains, are always sure to be back in yet another sequel or “rebooting” of the franchise. Meanwhile, the mortals are of no interest except insofar as they can give us a comic or spectacular death. The only people who die in movies like this one, which depend on our sense that there will always be another life for any character who matters, are virtually — often literally — faceless, anonymous. They’re just there to contribute to the body count, which is an aspect of the spectacle. They are treated with as much contempt as the Joker treats his hapless henchmen. The measure of the seriousness of any dramatic work is whether it takes death seriously. By that measure, The Dark Knight is not only fundamentally unserious; it is a travesty.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.