Getting It

From The New Criterion, June 2008On my occasional visits to Starbucks, the ubiquitous coffee merchants, I try to refuse to use the private language the company has thoughtfully provided for the convenience of its patrons. Sometimes I forget and ask for Tall, Grande or Venti, but usually I ask, defiantly but with some embarrassment, for small, medium or large, because I resent being forced into a greater intimacy than I desire with the Starbucks corporate culture. I want to be a customer, not a member of the Starbucks Club who validates his membership along with his entry on the premises by speaking the Starbucks idiolect. Doubtless the marketing department in Seattle has tested it to a fare-thee-well and found that most people are not like me; most people are happy to use the special, European-sounding jargon — the Stargot, as we might call it — because it flatters them into the belief that, along with their coffee, they have purchased at a very reasonable price admission to an exclusive circle of coffee-drinkers who are socially a cut or two above those who drink from the caffeine-springs of Dunkin Donuts or Ma’s Diner, where they use ordinary English.

Back on the other coast but with considerably less subtlety, The Washington Post has long been engaged in a similar exercise. Those who don’t live in the Washington D.C. area — or “market,” as we laymen have learned from the ad-men to call it — are spared many of the annoyances that we who live here must suffer, but to my way of thinking few of them can be quite so irksome as the relentless, never-ending radio advertising campaign for the Post which ends with that newspaper’s supremely irritating slogan: “If you don’t get it, you don’t get it.” Was ever such a crass appeal to intellectual snobbery by an organ purporting to be an arbiter of public tastes and morals? Join the “exclusive” club of subscribers to The Washington Post, we are told, and we will obtain access to the Hermetic knowledge that will clue us in about the world in a way that no other news source will do. Read it and you too, presumably, will be able to assume the Post’s arrogant air of knowing better than almost anyone else about almost anything. Who, we must wonder, is the target audience of such a campaign?

The idea of “getting it” — or not getting it — is also, perhaps, meant as a reminder of the catch-phrase that obtained some currency during the Clarence Thomas hearings 17 years ago. My how the time flies! Then, you may remember, even women of hitherto unsuspected feminist tendencies seemed to be popping up daily to add their voices to the chorus of those who had wowed a national audience by saying that, on the subject of sexual harassment, men in general or some particularly disfavored group of men such as conservatives, Republicans or Clarence Thomas and his defenders “just don’t get it.” The beauty of this line of argument was that it didn’t even depend on the otherwise central question of whether or not Mr Justice (as he now is) Thomas had or had not made inappropriately sexual comments to Miss Anita Hill. That hardly seemed to matter next to the fact that any man could be equally guilty simply by deploring the introduction of gossip and tittle-tattle into so solemn and public an occasion as the Senate confirmation hearings of a nominee to the Supreme Court.

Any attempt to preserve a decorous distinction between public and private, that is, amounted to making light of sexual harassment in the eyes of women who had been educated to regard the personal as political — and vice versa. Those who took a different view didn’t “get” what a serious offense against the post-feminist proprieties even merely verbal and non-contact sexual harassment was. Never mind the proprieties, however. The feminists themselves forgot about them quickly enough when, a few years later, it was Bill Clinton doing — or allegedly doing — the harassing. The real point of the not-getting-it charge, as it now seems, must have lain in the appeal to cognitive exclusivity. Progressive thinkers have always regarded themselves as an élite, as much for simply thinking as for what they think, and much of progressive politics involves trying to convert this intellectual and political élite into a social one. That’s why celebrity politics is so important to them. We may not know whose ideas are the best, but we know which ones are pleasing to the best people.

Naturally, no one wants to be outside the circle of those who “get it” — a formulation once applied mainly to jokes but now used to indicate a political group-identity which defines itself in part by stressing the stupidity of those who do not share it. To be among those who “get it” is not only to hold a certain set of views that make one reliably progressive but also, by holding them, to be a member of the progressive club— which, like the Starbucks club, is decidedly up-market socially. The phrase, both before and after The Washington Post got their inky hands on it, was really an exercise in political branding, in wearing the cool T-shirt or flip-flops or sun-glasses, all with the labels on the outside, and not the tacky or down-market knock-offs from Wal-Mart. Unsurprisingly, then, “getting it” involved, among many other things, hostility to Wal-Mart itself — and, less vocally, to the sort of people who continue in defiance of fashion, both political and merchandising, to patronize its numerous emporia.

Back in 1992 — known at the time in some quarters and partly as a result of the Thomas-confirmation hearings the year before as “the Year of the Woman” — the soon-to-be President Clinton was as cool as anybody. Nobody would have dreamed of accusing him of not getting it. Indeed, his chief claim to electoral advancement was that he did get it, as the older, stuffier, more conservative first President Bush, instantly notorious for not recognizing a supermarket scanner or checking his watch while his opponent was demonstrating his compassion, obviously did not. So finely attuned were the Clintonian antennae, indeed, that he “got” things invisible to almost everyone else. He got, for instance, that his opponent was responsible for “the worst economy in 50 years” when the recession he was referring to had already ended and was in any case the shallowest in 50 years.

The point of this rhetorical overkill — which has been repeated, with variations, by the out-party in every election since — was nothing to do with “the economy, stupid.” The point was about “getting it” and, therefore, not being stupid. People felt bad about the economy, just as they do now, whatever the statistics say. That’s what Governor Clinton “got” and, predictably, what the second President Bush is routinely accused of not “getting” for refusing to call the current economic downturn a recession. Never mind that the standard definition of a recession among economists is two consecutive quarters of negative growth. This has not happened since 2001, but the progressive-minded have strong precedents for treating not dry statistics but their own pessimistic feelings about the economy, so easily transmitted to those not of the élite who are unsatisfied with their economic situation, as the thing that the non-progressive may be censured for not getting.

But in 2008, the role of the cool, the cognitively up-market candidate who gets things has been taken by Barack Obama, so that the would-be second president Clinton has been forced to run against him as an anti-élitist — and, to that extent, an anti-progressive, the natural spokesman for the socially conservative Democrats that Senator Obama was injudicious enough to look down his nose at in San Francisco recently (see “Smear Tactics” in The New Criterion of May, 2008). There are numerous ironies about this. Last November, Mrs Clinton was described in the media as a “rock star” (see “Clooney Tunes” in The New Criterion of December, 2007); six months later she looks more like “the psycho ex-girlfriend of the Democratic party,” as some in the blogosphere have taken to calling her. But the greatest of these ironies is that the Wellesley-feminist and principal victim of her husband’s inability to “get it” when it came to sexual harassment should now by repudiating the cool politics of empathetic condescension that brought her into the public eye and onto the national stage in the first place and eagerly pursuing the defiantly not-getting-it Bubba vote.

Yet there is some precedent for this transformation. As Michael Crowley points out in a thoughtful article in The New Republic, there were those in among the media élites at the time of the Monica Lewinsky affair who regarded both Clintons as a species of white trash:

The Clintons find themselves victimized and under siege. The presidency is being stolen from them. The press is out to get them. They deride elites and champion the masses. They live in a constant state of emergency. But they will endure any humiliation, ride out any crisis, fight on even when fighting seems hopeless. That might sound like a fair summary of how Bill and Hillary Clinton have viewed the past five months. But it also happens to describe what, until now, was the greatest ordeal of the Clintons’ almost comically turbulent political careers: impeachment. That baroque saga hardened the Clintonian worldview about politics and helps to explain their approach to this brutal campaign season. The Clintons have been here before, you see. They’re being impeached all over again.

This was also the point of a Wall Street Journal editorial celebrating the abandonment of the former first couple by so many former Democratic loyalists. “It took 10 years, but you might say Democrats have finally voted to impeach.” Enough Democrats, that is, to deny her the nomination, but very far from all Democrats. And those who are left still on board the sinking ship, that rump of the Roosevelt coalition of Southern and blue-collar whites, were once thought even by the élitist, getting-it sort of Democrats to be necessary to victory over the Republicans. As Paul Begala, one of the die-hard Clinton-supporters, aroused the fury of the Obamaniacs by putting it, the Democrats cannot win with a coalition limited to “eggheads and African-Americans.” That, he said, was what the candidacy of Michael Dukakis showed in 1988.

If this was true 20 years ago, I’m not so sure it is today, for you have to include not just the eggheads but also the would-be eggheads — a presumably much larger if still indeterminate number — who imagine that it is a validation of their intellectual aspirations to be reading the Washington Post, drinking Starbucks coffee and supporting Senator Obama. Political branding for the age of Starbucks has perhaps not yet been fully tested. Senator Kerry in 2004 was an egghead and almost as cool a brand name as Senator Obama is today, and he came within 100,000 votes in Ohio of being our second cool president — the third if you count President Kennedy, whose coolness was mainly retrospective. Now, promiscuous comparisons between BHO and JFK — a man who, in real life, was a political street-fighter at least the equal of Hillary Clinton — ought to tell us what we’re in for. Here’s David Ignatius “getting it” — by his own lights, at least — in the Post:

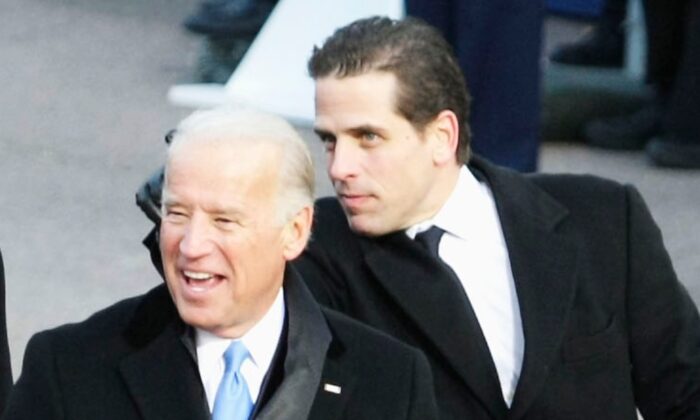

The presumptive Democratic presidential nominee is far from perfect. But he has demonstrated the most mysterious and precious gift in politics, which is grace under pressure. Obama has remained “Mr. Cool,” even when his campaign seemed to be blowing up around him. He didn’t do the politically expedient things: He didn’t wear his patriotism on his lapel with an American flag pin; he didn’t promptly disown his race-baiting former pastor, Jeremiah Wright; he didn’t apologize for comments by his wife, Michelle, that many Americans found unpatriotic. You can say what you like about the substance of these positions, but the interesting fact is that Obama didn’t flinch. . . What’s compelling about Obama is that fusion of grace and ambition. He’s playing for the highest stakes, but he makes it look easy. That cool, graceful quality evokes John F. Kennedy and the Rat Pack — all these sleek, handsome men in silk suits and skinny ties who never break character, never miss a beat.

The ludicrousness of such stuff as serious political commentary does not take away from the possibility that a majority of American voters might, in the end, think about the candidates in a similar vein and vote for the would-be Rat Packer just because he is so cool. Alternatively, it may be that, as Daniel Finkelstein of The Times of London says, Senator Obama may prove to be “too cool to be president.” A propos of the Senator’s comments about the “bitter” God- and gun-nuts, Mr Finkelstein writes:

There are things that politicians can say and things that analysts can say, and they are not the same thing. Inevitably, for instance, his comments will be interpreted as a patronising slur on religious people, even though he is religious himself. But Obama didn’t respect that distinction. And I think his slightly lofty, stand-off manner is the reason. He seems sometimes to be looking at the election from the outside. He sometimes seems to be standing back and marking his nation like an independent assessor. And, although this may seem to some like an odd comparison, there is a little bit of Michael Dukakis’s emotion-free character lurking even in Obama’s most rousing rhetoric. Republicans are concerned that McCain is too hot tempered. But Obama may prove to have an even bigger problem arising from something usually seen as an advantage. He is the cool candidate. Could he be too cool to win?

|

If so, the erstwhile rock star, Mrs Clinton, has to be considered (in this respect at least) also too cool to win, basing as she did a major part of her appeal on her own greater electability. In doing so, she echoes her opponent’s élitism. Vote for me, she says, not because I will be the better candidate, but because the hicks and the rubes will be panicked by the gaffes of my opponent and will send him down to defeat against our common enemy, the Republicans. We are all journalists now as Scott Gant says in his book of that title — except that he hasn’t quite got it right. We are all pundits now; we are all commentators now; we are all news analysts and columnists and editorialists now. We not only dig out our own news but we also have to tell ourselves — and anyone else who will listen — what to think about it. That the candidate himself should engage in such detached, analytical reasoning about his candidacy must inevitably come to seem less and less remarkable.

We already know that many voters in our post-modern, media-savvy age can be appealed to on the basis of electability. This was made evident by John Kerry’s victory in the Democratic primaries of 2004 (see “Root Causeism and Electability” in The New Criterion of April, 2004) — though it doesn’t necessarily follow that the Democratic electorate will invariably believe a candidate’s assertion of his or her own greater electability. We also have to consider that there is less and less to go on in evaluating a candidacy apart from electability. Within the two main parties, the candidates views are virtually indistinguishable. They’re all competing for the same voters, and those voters — taking their cue from the brainy and sophisticated media — are deciding on the basis of electability. That means that all the views of every candidate are determined not only by what views most people want him to hold but also what most people think most people want him to hold.

In other words, at the primary level at least, any campaign must go through not one but two filters designed to rid the candidate’s politically substantive plans and programs, and even his jokes and obiter dicta, of anything eccentric or alienating to significant numbers of voters. He not only has to perform on the political stage, but he also has to critique his own performance — not least because, if he doesn’t, the critique will be left to his political enemies. If we have not already done so, we will get used to politicians being their own critics. We are already used to them in this role, if they are suitably disguised as “spokesmen” expected to “spin” their own debate performance after the fact. Senator Obama falls more easily than most into the critical role, as Daniel Finkelstein noted; all he has to do is avoid henceforth the cardinal sin for any politician of criticizing the electorate.

In this he could learn something from the newly-elected cool mayor of London, Boris Johnson, a man who actually was a pundit himself up until a few months ago. But he was taken in hand by an Australian political Svengali named Lynton Crosby, coached not to commit any more of the “gaffes” for which he had become famous (including insults to the entire populations of the cities of Liverpool and Portsmouth — who admittedly had no vote in the mayoral election) and so made presentable enough to defeat the two-term incumbent Labour mayor, “Red Ken” Livingstone. If Boris, why not Barack? One possible answer to that question is the fact that Mr Johnson’s self-deprecatory wit and sense of humor remained visible even through the gauzy wrappings in which he had been swaddled by his handlers. These qualities are, shall we say, less salient in Senator Obama — and all but non-existent in Mrs Clinton.

But perhaps it is enough of a compensation that, much more than either his now forlorn Democratic rival or the triumphant new mayor, Senator Obama is obviously the premium political brand. That will make for an interesting test in November, and maybe even a final answer to the question of whether or not the media culture has managed to produce enough politically style-conscious celebrities and would-be members of the cognitive élite to make up a majority.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.