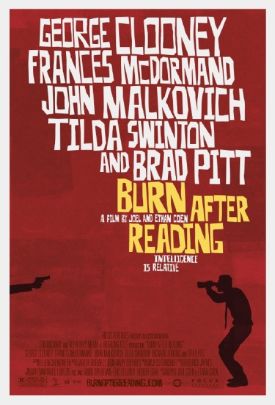

Burn After Reading

In an interview with the New York Times to coincide with the release of their new film, Burn After Reading, the Joel and Ethan Coen demonstrated their high spirits for the benefit of the delighted interviewer, Bruce Headlam, who ends his piece with a context-less ejaculation: “‘Hey,’ Joel said, his voice brightening, ‘didn’t Karl Popper go after Wittgenstein with a poker?’” This is a revealing error. It wasn’t Popper who went after Wittgenstein with a poker. There are so many conflicting accounts of what happened at King’s College, Cambridge, that night in 1946 that a whole book has been written about the incident, but everyone agrees that if anyone had a poker it was Wittgenstein, who waved it about as he argued volubly with Popper about whether there was any such thing as a moral rule which a philosopher had a duty to respect. According to Popper’s account, when Wittgenstein demanded that he give an example of a moral rule, he responded: “Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers” and caused Wittgenstein to walk out angrily.

Somehow it seems appropriate that Joel Coen should have transformed in imagination a philosophical defense of moral order into an innocent philosopher’s wild and unexplained act of aggression with a poker. For the Coens themselves have abandoned the respect for moral order that they still displayed as recently as Fargo (1996) — and perhaps any belief in morality itself. Burn After Reading delights in presenting us with a dummy plot as a way of denying any moral significance to their own narrative. There are a number of events that have to do with one another through coincidence but without any chain of causation between them of the sort that would expect if the movie were to make sense as a whole. In fact, it is in a way a movie about coincidence, but coincidence without meaning or significance. The result is an exercise in mere absurdism.

Accused by a Mormon associate of having a drinking problem, Old Princetonian Osborne Cox (John Malkovich) angrily resigns from the CIA to write his memoirs. Unbeknownst to him, his wife, Katie (Tilda Swinton), is having an affair with the easy-going exercise-obsessed sex-addict Harry Pfarrer (George Clooney) while, unbeknownst to her, Harry is heavily into Internet dating. Katie thinks that Harry is going to leave his wife, the long-suffering Sandy (Elizabeth Marvel) when she divorces Osborne, but he just wants to stay married to Sandy while having fun on the side. Meanwhile, one of Harry’s Internet dating partners, personal trainer Linda Litzke (Frances McDormand) — who also has a date with Osborne Cox’s Mormon accuser — accidentally comes into possession of an electronic copy of Cox’s memoir and tries to use it, through fair means or foul to raise money for the cosmetic surgery she thinks she needs to attract men. “If I’m going to reinvent myself, I need these surgeries,” she says. She imposes on Chad (Brad Pitt) her brainless but good-natured colleague at the Hardbodies gym, to help in her schemes of blackmail and treason while remaining oblivious to the shy romantic interest in her displayed by her Hardbodies boss, Ted (Richard Jenkins).

That’s the set-up for a highly complicated plot which is never really set in motion. It could easily be a movie about strong women and weak men, or a traditionally sentimental paean to the old Hollywood trope of finding the object of your heart’s desire right under your nose. Or about the comeuppance of Osborne’s intellectual arrogance which seems to regard the whole world, apart from himself, as “morons.” But it turns out to be none of these things. Especially not the last. Instead, the Coen boys show themselves to be Osborne’s equal in intellectual arrogance. For each of the actions implied by the situation they have so painstakingly set up — Katie’s divorce of Osborne and Linda and Chad’s attempt to blackmail him, Harry’s realization that his mistress is the same “cold, stuck-up bitch” that she calls his wife and the wife’s discovery of his infidelities, poor Ted’s attempts to ingratiate himself with Linda, his object of secret worship — all these things remain essentially unconnected but lead to separate disasters for everyone except Linda, who by sheer luck gets her cosmetic surgeries paid for by the CIA.

It’s like the ending of an Evelyn Waugh novel only without the carefully prepared narrative leading up to it which creates a sense of meaning in spite of itself. Here, nothing means anything. Not for the first time, the Coens appear to be adopting a point of view like that with which the film begins and ends — that is the god-like perspective of a satellite photograph from space — and crying, simply, “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” There is something fundamentally unattractive about such arrogance, something cold and cruel and terminally detached from human striving and suffering, like that of the gods of Homer. But Homer only observes the actions of the gods; he doesn’t think he’s a god himself. I’m not so sure about the large-brained but show-offy Coens.

It hasn’t always been so. At this distance of time, I find that what I remember best about Fargo are the final words of Miss McDormand’s Marge Gunderson to the surviving bad guy, played by Peter Stormare: “So that was Mrs. Lundegaard on the floor in there. And I guess that was your accomplice in the wood chipper. And those three people in Brainerd. And for what? For a little bit of money. There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’tcha know that? And here ya are, and it’s a beautiful day. Well. I just don’t understand it.” In their context, there is something almost heartbreakingly lovely about these words, something that puts the whole film into a satisfyingly moral perspective. They are the heart and the soul of it and what makes it a great movie. The comparable quotation from Burn After Reading, are these words from the unnamed CIA chief played by J.K. Simmons: “So we don’t really know what anyone is after?. . . Well, report back to me when — I don’t know. When it makes sense.”

But of course the point of it is that it never does make sense. Tiny bits of the action do, at least to the people involved in them, but there is no sense to be made of the thing as a whole. And that’s the point. As in their previous film, the Oscar-winning No Country for Old Men, the Coens have gone all in for chaos theory. The sense of their movie is not only that it makes no sense but that there is no sense to be made of anything. Like No Country, it seems to delight in chaos and the lack of any moral order to the universe. At the time some critics took Fargo to task for laughing up its sleeve at the good burghers of Brainerd, Minnesota, including Marge the pregnant police chief, and her duck-painting husband, Norm (John Carroll Lynch). I thought that, beneath their sophisticated urban humor at the expense of these country folk, the Coens respected the basic decency of Marge and Norm and all that they stood for and, in fact, had made such a point of it precisely because the film needs that goodness to stand against the evil deeds they are representing in the main action of the film. Now I’m not so sure.

For Burn After Reading is the culmination of a pattern of celebrating amorality and meaninglessness. In their more recent films, the brothers have cut themselves loose from morality altogether. Even a mock morality like “The Dude abides,” from The Big Lebowski (1998) would have been something with which to make sense of the world, but they don’t do that kind of thing anymore. Now they’re into merely absurdist humor, only without the political edge to it that the Theatre of the Absurd had back in the olden days. Instead, we have the same CIA guy summing up: “What have we learned? Not to do it again, I guess. But what did we do?”

Actually, there is a political edge, but it’s tacked on at the end as Tuli Kupferberg’s “CIA Man” is sung (if that’s the right word) by the Fugs over the closing credits — as if the moral chaos we have just witnessed could be construed, at a pinch, as a 1970s style radical statement against the American fascist-imperialist state. The idea is so ridiculous that the thing merely counts as yet another absurdist touch. And the point of all the absurdity is only to affirm that our world offers no hope to those who, like Karl Popper and most of the rest of us, try to imagine that it has some sort of moral order to it. It may be that it doesn’t, of course. Doubtless the Coens sincerely believe that it doesn’t. But at least we might have expected from the authors of Fargo a recognition of the tragic nature of this moral apocalypse. There’s something inhuman about showing it only to laugh at it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.