Martian Chronicles

From The New CriterionThe death at age 92 of Eric “Digger” Dowling last July 21st provided the occasion for the British national tongue to wag — and yet again to seek out a favorite cavity in one of its formerly sturdiest molars. This gaping national shame was John Sturges’s movie adaptation from 1963 of Paul Brickhill’s book, The Great Escape. Dowling was the real life version of the character played in the movie by Charles Bronson, Danny the Tunnel King. All the obituaries mentioned that the real, the British Tunnel King had not been a fan of the movie, and that he was particularly censorious about the famous scene in which Steve McQueen attempts to jump the barbed wire perimeter fence on a motorcycle. That, the Digger had once observed, was “well over the top” — which, ironically, is just what poor Steve McQueen wasn’t. But the perpetual source of annoyance to the British media and that which is always guaranteed to get a rise out of them is the fact that the real-life escapers from Stalag Luft III were all British, whereas the four most glamorous and interesting ones in the movie — James Coburn and James Garner played the other two — were depicted as Americans.

Nor, they will be sure to tell you, was that the first or the last such insult to Britain’s national pride.

Churchill was enraged in 1945 [wrote Ben Macintyre in The Times] when Objective, Burma!, starring Errol Flynn, depicted a raid by British and Commonwealth troops as an American triumph. Fifty-five years later, in U-571, the British coup in capturing the Enigma machine from a German U-boat was baldly depicted as the work of American submariners.

Of course Hollywood was, as it nearly always is, responding to market pressures in order to give the preponderance of its audience the version of the war’s history it wants to see. It’s not as if the rest of us don’t look in history’s glass for what pleases us. Consider, for example, Mr Macintyre’s own version of the post-war period:

The austerity of the 1950s and the cultural clashes of the 1960s encouraged film- makers to look back with one-dimensional nostalgia on the war, as a time of simple moral verities, when Allied Good triumphed over Axis Evil and every man in British uniform was a hero. But war is never as black and white as the black- and-white films made it seem. Armed conflict is usually a grim and grey area.

Dear, dear. Now where have I heard something like that before? I’m afraid that what we have here is yet another example of the media’s perennial conceit that “reality,” in all its glorious grimness and grayness, is perspicuous to the truthful reporter, whose task is thus to correct those verity-loving, one-dimensional folk who prefer to look for the more crowd-pleasing black and white version. Fair enough, perhaps — just so long as the media don’t exempt themselves from the charge of seeing what they want to see.

Some hope! The intellectual pride of the “reality” mongers just isn’t up to such humility. Look at the latest rewriting, not just of the war’s but of the whole century’s history, the better to fit it to the popular preconceptions of our own day. This was undertaken by TV’s Niall Ferguson, a Scottish-born, Oxford-educated Harvard professor of history and academic superstar ,in late June and early July on PBS. Nothing if not intellectually ambitious, Professor Ferguson’s one-man show, “The War of the World,” took not only the one formerly known as “the good war” but also the bad war that came before it and the ambiguous war that came after it and slotted all three, plus an assortment of other conflicts amounting (he says) to about a hundred resulting between them (he says) in 20 millions of dead, into one unified theory of 20th century conflict. And you’ll never guess what it is, what all that killing turns out to have been about — though, of course there are no prizes for guessing that we simple-minded, one-dimensional nostalgists turn out to be wrong once again.

Professor Ferguson has discovered that all these wars were really about racism and race hatred — on the part of Britain and the U.S. as well that of such familiar monsters as Hitler, Stalin, Tojo and Slobodan Miloševiæ. Oh, there were other factors at work too: the decline of the multi-ethnic Western empires, the resurgence of the East, economic crisis. But race hatred is the original sin which unites in moral dishonor Americans — shown in a clip by an anonymous cameraman shooting wounded Japanese soldiers — and British — shown bombing German cities — with their erstwhile enemies. The main point for us all to get through our heads for the umpteenth time is the same as Ben Macintyre’s, namely that, even if the bad guys really were bad, “we” by God weren’t the good guys. Just, maybe, a little bit less bad. The professor takes the precaution of denying that he is engaged in drawing a moral equivalence, though how that might differ, if he were so engaged, from saying (as he does) that “Allied methods were comparable in effects if not in intentions to the very worst techniques of their enemies” is not at all clear to me. I wonder if he would have the face to say it to a survivor of the Holocaust, or of a Japanese prisoner of war camp?

And all this because “we” — Nazis and Japs and Brits and Yanks alike — are supposed to have “dehumanized the enemy to kill him”! Of what war could that not be said? Indeed, of what killing could it not be said? If “humanity” is afforded all the dignity with which he would endow it, the dehumanization is presupposed by the killing, and the professor’s dazzlingly clever key to all (20th century) conflict amounts to little more than a tautology. The point of the exercise seems to me to be to find yet another way to debunk the heroic view of war — any war would do, but you get extra points for debunking WWII — and re-affirm for an audience of those more disposed to love their own powers of ratiocination and sense of moral self-satisfaction than their country that the real heroes are the intellectuals who can interpret it for us and moralize about it persuasively. The infant Niall, growing up in his Glaswegian na veté, had once been told the triumphalist version of the century’s history, he tells us — the version in which “the good guys, that was the Western democracies, won both World Wars and the Cold War. Well in this series, I want to tell you that that was all wrong.”

“TV said that?” as an astonished Homer Simpson once observed. Yes indeed. So much (once again) for the simple moral verities! We should be grateful, I suppose, that the peripatetic professor, shown whizzing around the world from one formerly hot but currently cool spot to the next, often while in transit, at least allowed some of the blame for the war to fall upon its traditional recipients in Berlin and Tokyo. Other World War II revisionists such as Patrick Buchanan and Nicholson Baker have lately been presenting the whole thing as the fault of that blunderer Churchill and his partner in war crime, Franklin Roosevelt. Can it be only coincidental that this take on the war of 1939-45 — that if only our leaders had been smart enough it need never have been fought at all — exactly coincides with the media’s take on the war of 2003-2008 in Iraq? At any rate, you can understand why I might harbor the suspicion that this is the story that the book-buying public, like the PBS watching audience, wants to hear just as much as those 1950s-vintage simpletons wanted to hear the heroic one.

Professor Ferguson’s title was of course a play on that of H.G. Wells’s novel of 1898, The War of the Worlds, in which technologically advanced Martian supermen invade suburban London and lay waste all that they encounter. This book the professor considers not science fiction but “astonishingly prescient,” and he illustrates the point right at the outset of the series by reading out passages of Wells’s description of the effect of the Martian “Heat-Ray” on fin de si cle London and its inhabitants as we watch archive footage of World War II American flame-throwers and incendiary bombings of German cities. All this gives the prof. the opportunity to kick things off with an overview of the millions of 20th century dead to which he appends the following portentous comment: “Those responsible were not Martians. They were human beings who in order to justify the killings defined other human beings as aliens. The question is why? What made the 20th century in spite of all its economic and material progress, the most violent in history. What made men act like Martians?”

You’ve got to believe that only someone as brilliant as Harvard’s and Oxford’s Professor Ferguson could be quite so oblivious to the fantasy world his argument is inviting us to inhabit with him. There are no Martians, you see, so no one can behave like one. The killers of the 20th century were in fact behaving exactly like human beings — the human beings of every previous century whose bloodthirstiness, if not their technological capacity for satisfying it, has been pretty constant throughout recorded history. In other words, it was because of, not in spite of, economic and material progress that the 20th century was so violent, not some mysterious new urge to start behaving like imaginary Martians. Human beings are, we may say, never more human than when fighting and killing. Like it or not, it’s what we human beings do and always have done. But Professor Ferguson, the historian, ignores all that history in order to pretend that we live in a Wellsian world of human solidarity and brotherhood into which, during the 20th century, fratricidal conflict suddenly and, but for him, unaccountably intruded.

What his little history amounts to is another chapter in the quest of the 20th century intellectual — every bit as absorbing to our eggheads as that for the philosopher’s stone was to those of the middle ages — for the holy grail of a universal point of view. The professor is of course far from alone in being a chauvinist for “humanity” and finding it irksomely limiting to be British. Or perhaps Scottish. It sometimes seems that most Britons today don’t like being British and are ashamed of their national history in the name of a larger world-community with which they prefer to identify themselves. Lots of Americans, I’m sorry to say, feel the same about our history. But it must be a hard shame to live with unless you have the consolation of some utopia, some “no place” of perfect “humanity” — in the fanciful, Wellsian-Fergusonian sense — in which to pitch your imaginary tent and from which to pontificate about the shame of your ancestors in treating each other like Martians. It’s such a tiresome conceit, and yet it’s one that PBS finds endlessly enlightening, doubtless because it provides those in this first circle of the media pit another opportunity for keeping their smug self-righteousness fully inflated.

|

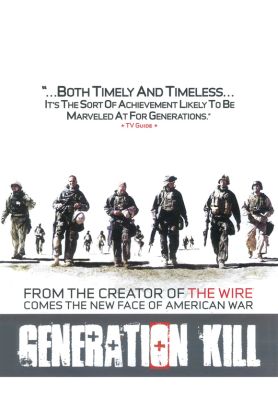

But why blame PBS or Professor Ferguson when the whole culture of the media and entertainment industries is riddled with similar assumptions about the world? No sooner had the professor subsided on PBS than over on HBO, the summer was enlivened by a mini-series about the war in Iraq written and produced by Ed Burns and David Simon, the creators of “The Wire” — which recently finished its multi-season run on the same network — and based on the book by Evan Wright called “Generation Kill.” As you might guess from the title, and as you would certainly guess from “The Wire,” the point is less preachy and abstract than but essentially the same as the Niall Ferguson’s, namely that the privileging of “humanity” over every lesser identity is bound to make those whose jobs routinely involve the taking of human life look like Martians. But at least in the case of the fictional-but-“based-on-fact” Marine reconnaissance platoon which the series follows most closely and whose members become individualized for us as it thrusts into Iraq in the invasion of 2003, the Martians are meant to be as engaging as they are scary.

This is accomplished partly by stressing the men’s own humanity in the form of emotional and moral frankness and partly by making them gloriously profane and outrageously obscene — the depiction of which qualities, along with the violence porn, is naturally the glory of a cable network like HBO in comparison with the broadcast PBS — and, at the same time, utterly politically incorrect. The homophobic and sexist jokes alone would have prevented it from being made, but for the ironic subtlety with which it attacks the American war in Iraq. It’s a clever strategy and one which mirrors that of the rest of the anti-war movement in seeking to portray our country’s warriors not as baby-killers — that was the mistake of many, including John Kerry, in the anti-Vietnam War faction — but as themselves the victims of buffoonishly incompetent or corrupt leaders and the false consciousness of the military culture that those leaders exploit. All of this is conveyed with hardly a reference to the leadership in Washington beyond an occasional ironic thrust, as when one marine shouts “Vote Republican!” at some hapless Iraqi beneficiary of the invasion.

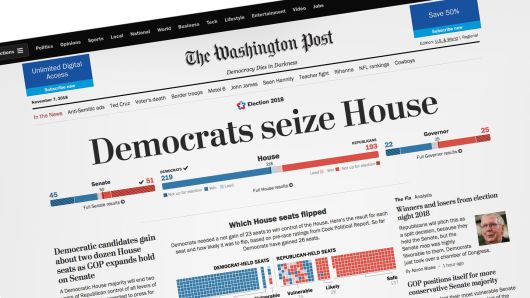

Irony is of course the nectar of the intellectual Olympus, and the reason why both “The Wire” and “Generation Kill” have elicited such lavish praise (“grippingly powerful. . . the Platoon of the Iraq war. . . among the truest and most trenchant war movies of all time.” — Tom Shales, The Washington Post) in the media. In one episode of “Generation Kill,” for example, a trigger-happy lance corporal takes too literally the battalion commander’s proclamation of a free-fire zone around an Iraqi airfield that turns out to be abandoned and guns down a camel. All the rest of the guys make fun of him about this until he protests: “I didn’t mean to shoot an innocent camel, all right? I’m sure I shot people!” Sure enough, it later turns out that he did shoot “people” — a little boy who had been minding the camel and who is brought into the camp near death. The platoon’s medic and a delegation of its more conscientious members eventually shame the gung ho commander into dispatching the boy to the Marines’ own shock-trauma unit in the rear.

Thus, to the pleasure of having his political prejudices confirmed by something so obviously authentic and (therefore) true and his moral prejudices in favor of humanity over all ancillary allegiances flattered, the intellectual can add the cerebral satisfaction of having decoded the film’s subtle ironies — so much more telling (don’t you think?) than a direct assault on the Masters of War themselves. Yet, beneath it all, “Generation Kill” is as simple-minded about human conflict as Professor Ferguson. Or, for that matter, as the real phenomenon of the summer, Christopher Nolan’s new Batman movie, The Dark Knight, which, at the time of writing, has just taken over the third slot — behind Titanic and the original Star Wars — on the table of the highest-grossing movies of all time. Mr Nolan showed that all it takes to dress up a typical superhero fantasy as high art (“goes darker and deeper than any Hollywood movie of its comic-book kind” — Manohla Dargis, The New York Times) and to make a mint of money doing it is a bit of agonizing about how outraged one’s humanity is by the prospect of “violence” perpetrated by the forces of law and/or order against a psychotic mass murderer to whose “level” they thus reduce themselves.

By the way, the only motivation for this murderer’s multiple crimes seemed to be to prove to the putatively good guys that, in the words of Professor Ferguson, their “methods were comparable in effects if not in intentions to the very worst techniques of their enemies.” So, really, he’s the good guy, just like Professor Ferguson, because he’s the one who proves to the hero that he’s no hero after all. No wonder, then, that the actor who portrayed him, the late Heath Ledger, has posthumously become such a pop-cultural “icon.” More importantly, The Dark Knight showed that such sophistry, along with an ostentatious solicitude towards “humanity,” is not the unique prerogative of intellectuals anymore. By now this is every aspirational egghead’s favorite pseudo-profundity. Otherwise, neither Niall Ferguson nor Ed Burns nor David Simon nor Christopher Nolan would been able to turn a tidy profit by feeding it back to them.

Nor, for that matter, would yet another of the summer’s superstars, Senator Barack Obama, have thought it in the least likely that it would help him to get elected as president of the United States to give a speech with the Fergusonian title of “A World that Stands as One” before 200,000 cheering Germans to whom he introduced himself as a “proud citizen of the United States, and a fellow citizen of the world.” Like Professor Ferguson, too, who also pontificated in front of the Berlin Victory Column or Siegessäule, the Senator noted that the relics and reminders of war “insist that we never forget our common humanity.” You might never know that there could ever again come a time when a man might have to choose, as men have had to choose for millennia, between their common humanity and some more exigent identity as members of nation, tribe or family.

Senator Obama spoke in Berlin on July 24 — 79 years to the day, so Wikipedia informs me, after the implementation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact “providing for the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy.” Just look how successful that turned out to be! It also happened to be (again thanks to Wikipedia) both my 60th birthday and that of the Looney Tunes character and one of Bugs Bunny’s many foils, Marvin the Martian. There ought to be a lesson in there somewhere.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.