Trash Triumphant

From The American SpectatorWalking past my neighborhood book store the other day, I noticed a display of books in the window under the following notice: “Olsson’s Recommended Reads for Moral Degenerates.” Underneath were such titles as Mary Roach’s Bonk, Peter Sagal’s Book of Vice, something called The Deviant’s Pocket Guide and several others of a similar tendency. Doubtless the display, like the books themselves, was intended as a joke by people who find the idea of moral degeneracy attached to anything sexual comically outdated — people who don’t really believe that there is any such thing. Of course, it’s no news that there are lots of such people around. What was interesting to me about this celebration of moral degeneracy was the assumption of those who put it together that anyone likely to come into the shop would be in on the joke. It’s not the only indication that the world of books and ideas is becoming as much the exclusive preserve of our “progressive” heirs of the 1960s counterculture as the movie business already is. Conservative books are more and more relegated to the right-wing intellectual ghetto of publications like this one, which are the only places where they are likely to be reviewed.

Not only mainstream book-sellers but mainstream books can now take for granted the progressive “narrative” arising out of the 1960s. I mentioned in the last installment of “Conservative Tastes” (see “In Defense of Snobbery” in The American Spectator of July/August, 2008) David Hajdu’s Ten-Cent Plague, which celebrated the triumph of the comic book and its ethos over their many detractors in the 1950s — and, by extension, over traditional movie-making in the Hollywood of the 1970s. In the same vein is Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (Penguin, 490 pp., $27.95). Mr Harris takes the five nominees for Best Picture at the Academy Awards for 1967 — Bonnie and Clyde, Doctor Doolittle, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and In the Heat of the Night — as the foundation on which to build a similarly triumphalist account of the coming of “a new world of American movies” destined to sweep aside the fusty old habits of movie-making formed during the 1940s and 1950s.

The newest and hippest of these five movies was of course Bonnie and Clyde, which was a revolt not only against a style of film-making but against the values and assumptions of the middle-class audience that the movies had always sought to cater to in the past. That was what recommended the movie to Pauline Kael of The New Yorker whose review of the movie did so much to bring about the revolution. Writing in The National Post of Canada this summer, Robert Fulford suggested that, latterly, some of the makers of the revolution, including even Ms Kael herself towards the end of her life, were beginning to have second thoughts about what they had wrought.

It was only in the late stages of her New Yorker career (from which she retired in 1991) that some of her admirers began saying she had sold her point of view too effectively. A year after her death (in 2001) one formerly enthusiastic reader, Paul Schrader, a screenwriter of films such as Raging Bull and Taxi Driver, wrote: “Cultural history has not been kind to Pauline.” Kael assumed she was safe to defend the choices of mass audiences because the old standards of taste would always be there. They were, after all, built into the culture. But those standards were swiftly eroding. Schrader argued that she and her admirers won the battle but lost the war. Acceptable taste became mass-audience taste, box-office receipts the ultimate measure of a film’s worth, sometimes the only measure. Traditional, well- written movies without violence or special effects were pushed to the margins. “It was fun watching the applecart being upset,” Schrader said, “but now where do we go for apples?”

He concludes by noting that “not long before she died, Pauline Kael remarked to a friend, ‘When we championed trash culture we had no idea it would become the only culture.’ Who did?”

The worst thing about the triumph of trash culture is that people start to forget that it is trash. We all become a bit like the window decorator at Olsson’s for whom the concept of moral degeneracy only exists as a joke at the expense of uptight conservatives. Many of my fellow critics appear long since to have forgotten the difference between serious movies and cartoonish, super-hero fare like The Dark Knight, which was greeted on its opening this summer with the sort of rapturous reviews that would once have been reserved for only the finest examples of their time of the movie-maker’s craft — which, unfortunately, is what that movie has become for our time. That’s why, in the summer of 2007, as I wrote in these pages at the time (see “The Hero Vanishes” in The American Spectator of September, 2007), I presented a film series on The American Movie Hero at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. to explain and illustrate my view that the 1960s, in so many ways a watershed in American cultural history, was in none of those ways more of a watershed than when it came to America’s understanding of heroes and heroism. When real heroes were superseded by cartoon and super-heroes, we began to forget even what real heroes looked like.

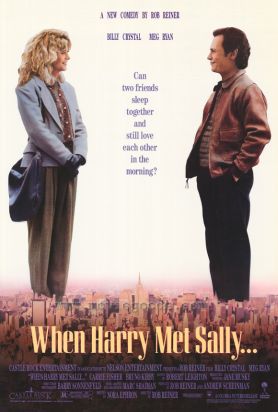

In the summer of 2008, my EPPC film series was an attempt to find a similar pattern in Hollywood’s treatment of romance. Starting with Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night of 1934 and continuing through Ernst Lubitsch’s The Shop Around the Corner (1940), George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story (also 1940), David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945), and Leo McCarey’s An Affair to Remember (1957) to Billy Wilder’s The Apartment of 1960, I showed what I considered to be a representative sampling of Hollywood romances as they existed before the sexual revolution of the 1960s. What came after that revolution, though it bore some superficial similarities to the old Hollywood romance, was as different from it as the post-60s hero was from his predecessor. The post-revolutionary romance was represented by Woody Allen’s Annie Hall of 1977 and Rob Reiner’s and Nora Ephron’s When Harry Met Sally of 1989. In both these movies the dramatic conflict, such as it was, had to do with finding some middle way between love and friendship. Old-fashioned ideas of romance and romantic comedy, which had been built upon the centrality and the exclusivity of marriage, gave way to what amounted to a hybrid of buddy picture and sex-farce as the assumption of a once-and-for-all marriage was replaced by that of serial “relationships.”

And, just as real heroes became unrecognizable, so did real romance. There’s a moment near the beginning of When Harry Met Sally when the title couple are arguing about the meaning of Casablanca in a way that suggests neither has the faintest idea of what the movie would have meant to its original audience. Ingrid Bergman’s going off with Paul Henreid at the end couldn’t have been her own choice to Billy Kristol’s Harry, who asks Meg Ryan’s Sally if she “would rather be in a passionless marriage. . .”

“And be First Lady of Czechoslovakia,” interjects Sally.

“. . . than live with a man that you have had the best sex of your life with just because he owns a bar and that’s all he does?” She says that she would, and so would any woman in her right mind. It’s simply a matter of being “practical.” Doubtless Nora Ephron intended such crassness as a joke at the expense of these children of the 1970s, but now we have got to the point where even people who ought to know better can hardly understand love and romance except in grossly physical terms. Harry concludes that Sally’s understanding of the movie is owing to the fact that she has not known “great sex” which also leads back to the central thesis of the film: that men and women cannot be friends. The unspoken part of that proposition, which seems to be borne out by the ending, is that men and women cannot be friends in a social environment that consists of a sexual marketplace like that of 1980s New York. This is what Carrie Fisher is referring to when she says to her husband: “Tell me I’ll never have to be out there again.”

Out there

, of course, means in the dating scene, displayed like a piece of meat on a butcher’s hook, or a small animal in a shelter hoping to look cuddly enough that someone will want to take her home. There is something deeply shaming about this, particularly for women, but they are paralysed and helpless participants in the sexual economy because the alternative of chastity or continence would be a massive setback for feminist and progressive ideas. As with the new heroism, the new romance is ultimately a political statement — a statement about why we no longer want either the old kind of heroism or the old kind or romance. And yet we don’t quite want to let go of them either, or else we wouldn’t be trying to reinvent them. That, I suppose, is some small reason to hope.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.