Enemies of the Good

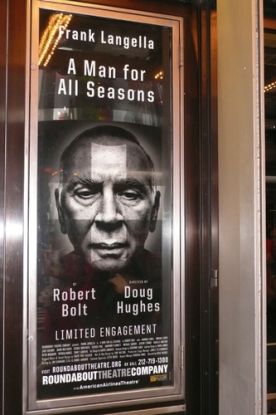

From The American SpectatorFrank Langella is a fine actor — for a movie star. But that he is primarily the latter rather than the former you can tell by the applause that greets him on his first entrance in this autumn’s Broadway revival, directed by Doug Hughes for the Roundabout Theatre Company, of Robert Bolt’s old favorite of 1960, A Man for All Seasons. It was clear on the night I attended that Mr Langella and not his impersonation of St. Thomas More was what the audience had come to see — which is just as well, since his Sir Thomas had something decidedly second-hand about it. He came just a bit short of the grand British style whose last exponent, Paul Scofield, only died about six months before Mr Langella took on what is still probably — on account of the 1966 film version of Bolt’s play — his most famous role. It sometimes seemed as if he was playing Scofield playing More, rather than the saint himself.

For what has Frank Langella — or any other actor playing the part today — have to do with saintliness that he should be demonstrating it to us? This is not a criticism of him but of an egalitarian culture that has forgotten how to admire, let alone venerate, those who represent the best of humanity. The echo effect in this portrayal of a 16th century saint, who was also very much a man of the world, is partly owing to the utter uncongeniality of saintliness — or even goodness — to the playful, parodic, post-modern culture that we all, willy-nilly, inhabit today. Watching Mr Langella’s performance reminded me just a bit of listening to the music of the Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov, which often sounds like a distant echo of 19th century, Brahmsian romanticism, as if the music were playing a long way off but still just audible. This is a form of musical grandeur from which, precisely, the grandeur has been taken away. What does that leave? A parody of something that insolently rejects parody.

Maybe something like this is what John Lahr meant when he wrote in The New Yorker of the Roundabout’s Thomas More that he was, of all things, a “cartoon,” a “caricature.” It’s strange to hear these words re-assuming their formerly pejorative sense. “Even the wooden beams and struts of the skeletal set, by Santo Loquasto, which divide the stage into large squares, contribute to the sense that ‘A Man for All Seasons,’ with its broad, garish narrative strokes, is a kind of classic comic book.” Of course, if it were Batman, or the Lion King, this would be high praise. I suppose that, when everything else is cartoon or caricature, that which is triumphantly neither of these things and, indeed, a rebuke to them, is what begins to look like the caricature.

What John Lahr can’t forgive Bolt’s Sir Thomas is his goodness. “Bolt is portentous without being penetrating. In this exercise in hagiography, the saintly Sir Thomas has no flaws, no appetites, and no depth. He is always wise, always modest, always decent.” What self-respecting critic will stand for that? Wickedness, by contrast, is like parody in being right at home with the post-modern sensibility. The devil is a laugh a minute, and irreverence is the coin of his realm. Goodness? Not so much. There is a kind of stolid seriousness to goodness — let alone saintliness — that seems repellent to us. That’s why John Lahr reacted to Bolt’s Sir Thomas with a sort of critical gag-reflex.

It’s also why Ben Brantley, the reviewer for The New York Times, began his review of the play by asking, “Is it heresy to whisper that the sainted Thomas More is a bit of a bore?” No, not heresy exactly. Even the Inquisition, though it might have been puzzled by the claim, could have found nothing contrary to the teachings of the Church in being bored by either heroism or saintliness. But to find these things boring is, I think, a sign of a lack of imagination in someone who lives in the secularist’s paradise of 21st century New York, where not only martyrdom but the existence of any principle worth dying for is far more remote even than it was in 1960. People like Messrs Lahr and Brantley dislike being reminded that it has ever been otherwise.

This imaginative failure does lead to some bizarre critical judgments, as when Mr Lahr writes that Bolt “is uninterested in complexity, and certainly unable to demonstrate it,” or when Mr Brantley writes that “Mr. Bolt’s script . . . neglects to include several essential ingredients for a compelling dramatic hero. Like conflict, doubt, vacillation and change.” It’s not possible, even in the pages of The New Yorker or The New York Times, to be so blind as not to be able see either the moral complexity or the conflict in A Man for All Seasons. If we mentally supply the word “inward,” it helps a little, though my own imagination boggles before the effort of understanding how it remains possible not to see the play’s outward complexities and conflicts as reflecting an inner struggle that the hero is otherwise powerless to give expression to.

Mr Brantley’s characterization of Bolt’s Sir Thomas as a study in “monolithic goodness,” like Mr Lahr’s rather comical attempt to use the word “hagiography” in its common, pejorative sense in describing a literal saint’s life, is a tip-off that what we have here is our old friend nuance, the liberal shibboleth constantly used to criticize those who act for the good — or to paralyze those who might be tempted to act for the good. As Barack Obama put it to Rick Warren, “a lot of evil has been perpetrated based on the claim that we were trying to confront evil. . . . Just because we think our intentions are good doesn’t mean that we’re going to be doing good.” Rather the reverse, in fact — or so it seems to me he wants to say.

There’s complexity for you: the complexity and the moral satisfaction of sheer passivity. Goodness for the liberal can only mean helpless victimhood, as in Schindler’s List and other Holocaust studies — the most recent of which is The Boy in the Striped Pajamas — or such fantastical variations on the theme as José Saramago’s Blindness, a movie-version of which also came out this fall. The blind doctor in that film, played by Mark Ruffalo, who has no moral choices to make but is simply the victim of his own innocence and the viciousness of power, is today’s equivalent of St. Thomas More — and, some might say, a lot more boring.

In that film, directed by Fernando Meirelles, even Gael García Bernal’s villain seems boring to me. A caricature, to coin a phrase. But, generally speaking, evil is full of nuance, complexity and psychological conflict — to the point where even such obviously evil figures as Richard Nixon or George W. Bush are allowed to settle down beneath a warm blanket, not of forgiveness, exactly, but of understanding. As it happens, it is Frank Langella who, as you read this, will be pronouncing the liberal and post-modern culture’s benediction over the grave of our 37th president in Frost/Nixon, a cinematic reprise of the role he originated on Broadway last year. At the time of writing, I have not had a chance to see this film, but I look forward to the great actor’s take on old floppy-jowls. Perhaps he can bring about that magical, po-mo moment where, as Paul Farhi in the Washington Post puts it of the army of TV parodists at work during this election season, “the real person starts to seem like an imitation of the imitation.”

In the meantime, I will have to make do with Josh Brolin’s President Bush in Oliver Stone’s W. Either because Bush-hatred is fresher in the popular imagination than Nixon-hatred or because the Stone-Brolin combination is simply not a very good parody, this film didn’t get much in the way of kudos from those whose appetite for moral complexity and nuance you would think would have been amply satisfied by it. What Sir Thomas More calls “the thickets of the law” in which he hopes to find refuge from the devil himself is here replaced by the thickets of Oedipal psychology, as Mr Brolin’s boyish W. whines his way along from one political or military pratfall to the next, all the while lamenting that he gets no respect from his emotionally distant father, played by James Cromwell. Audiences didn’t care much for it either, judging by the anaemic box office. Maybe they thought the character looked too much like a caricature. Or maybe they are simply growing weary of a cultural milieu that is all caricature, all the time.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.