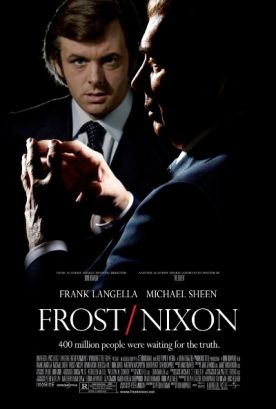

Frost/Nixon

Near the end of Frost/Nixon, directed by Ron Howard from a screenplay by Peter Morgan, there is a curious conversation at Nixon’s seaside villa in San Clemente between the two principals of the title during their final meeting. It takes place after the triumphant broadcast of their famous television interviews, which Nixon (Frank Langella) casually mentions he didn’t bother to watch. Frost (Michael Sheen) is about to leave when Nixon calls him back. The two men are supposed by the premiss of the film to have a certain fellow-feeling, which is an invention of the playwright’s, and the fictional Nixon confidentially asks: “Those parties of yours. The ones I read about in the papers. Tell me, do you actually enjoy them?”

“Yes, of course,” replies the fictional Frost.

“Really? You have no idea how fortunate that makes you,” fictional Nixon says. Then, by way of explanation, he adds: “Liking people. And being liked. That — facility you have with people. That lightness. That charm. I don’t have it. Never have. Makes you wonder why I chose a life which hinged on being liked. I’m better suited to a life of thought. Debate. Intellectual discipline. Say, maybe we got it wrong. Maybe you should have been the politician. And I the rigorous interviewer.”

This is not unlike things that the historical Nixon did say. He once told Stewart Alsop that, “I never was a buddy-buddy boy,” and everything we know about him suggest that this is true. It’s one of many reasons for thinking that there will never be another president out of that mold, either for good or for ill. There is also good reason to think Mr Morgan, who also wrote the play on which the film is based, was right in supposing that Nixon was highly sensitive to the slights of the “snobs” of the American governing classes who always looked down on him for his comparatively lowly social origins. It could have been a reason for his hoping to find a kindred spirit in Mr Frost, though there is no evidence that in fact he did so, as we see him doing in a fictional late-night phone call to his interviewer which, having been drunk at the time, he is later unable to remember.

Yet this little speech of his at the end as imagined by Mr Morgan has another significance which, perhaps, the author did not intend. For in a way, Nixon’s whimsical imagination in it has proven prophetic. Now the media and the politicians have indeed changed places. The gravitas which once belonged to the latter and the respect which it gave rise to are now the property of the former, whose self-importance is such as to take it for granted that the politicians must be explained and interpreted for us by their indispensable mediating agency. For who, wanting to know the true story of our political processes, would anymore think to ask a politician? They all speak in mere platitudes and banalities, since that is what the media demands of them — lest they be judged guilty of a “gaffe.” As a result, the language of politics is now a code which the services of the media are required to decipher for us.

Politicians have in turn become the sort of entertainers Mr Frost was once criticized for being — either rock stars (Presidents Obama and Clinton) or pantomime villains (President Bush, Vice-President Cheney). Looked at in this light, Frost/Nixon should be seen as part of the media’s ongoing effort to mythologize and glamorize this social and political transformation of the last 30 years. The rise of the media and other liberal bien-pensants to be the real governing élite of the country is a story with understandable charm for the media themselves, though it remains a question what the rest of us are supposed to make of it.

Even the moment seen as the peripeteia, the tragic reversal and revelation of hidden truth in the famous interviews, the moment when Nixon incautiously gives it as his opinion that “If the president does it, that means it’s not illegal,” could easily be turned around today — and not as a moment of hubris or tragedy. For you would have to look long and hard to find anyone, journalist or non-journalist, who did not agree in practice if not in theory with the proposition that if the media does it — whether “it” refers to the leaking of classified information or the defiance of court orders to protect felonious sources or the attempt to give aid and comfort to the enemy — that means it’s not illegal.

You’d think that this might give us a whole new slant on the self-evidently false proposition, so often quoted in the course of the media’s periodic re-damning of the late Mr Nixon, that in America no man is above the law. Hell, nowadays even Tom Daschle is above the law. Some hope, however, of ever seeing that curious and unprecedented state of affairs represented on the silver screen! Instead, the media and their Hollywood subsidiary go on mouthing “the lessons of Watergate” and appealing to us for sympathy with media underdogs against the would-be tyrants of the political and military establishment when it has been obvious for decades that the political and military establishment quail (or Quayle) before the power of the media “narrative” to cast them in the role of villain or buffoon.

Just look at the way Frost/Nixon conforms to that narrative — beginning with the order of the names in the title. As that might lead you to expect, the movie could be sub-titled: the Heroic Struggle of the Englishman, D. Frost, single-handedly to re-make the American Constitution so as to place the media in their rightful place above, not only the law but the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government. The film’s key passage comes not in the interviews nor the preparation for them with the help of the hard-bitten journalists James Reston, Jr.(Sam Rockwell) and Bob Zelnick (Oliver Platt) and the British TV producer John Birt (Matthew Macfadyen) — who later went on to become director-general of the BBC. These men predictably develop a certain respect for our hero, the man they once considered a mere entertainer, but even they are not admitted to the privacy of that hero’s Gethsemane moment of despair.

“I’m in this for everything I’ve got,” moans the brave little talk-show host to his love interest, Caroline Cushing (Rebecca Hall), in the late night intimacy of their chamber at the Beverly Hilton. “And there’s still no guarantee it will ever see the light of day. Why didn’t someone stop me?” Don’t worry, David! You’ll win through! Naturally, this dark night of the soul comes just before the dawn, the moment supplied to him by the invented drunken phone call from the ex-president which provided the key to unlock the enigma of his humanity. How, therefore, can we fail to admire this media entrepreneur who undertakes a task that everyone told him was impossible? How can we not know at once not only that he is bound to succeed but that his success must ultimately vault him into such stratospheric realms that, as a card at the end of the film tells us, his annual London cocktail party is regarded one of the social events of the season?

Actually, it says something not only about him but about the film that the real-life David Frost claims to be mildly embarrassed by his own, rather belated elevation to heroical stature, since “he regrets that ‘to build up the underdog thing,’ Peter Morgan’s script downplays what was already a distinguished television career before the interviews.”

The production notes (writes the Times reporter) describe Frost as “a jet-setting featherweight television personality with a name to make”, and the early part of the film depicts him as a shallow playboy whose career has hit the buffers. In the film, while Nixon’s team consider Frost’s surprising $600,000 offer for the interviews, the presenter is filming a low-budget item with an escapologist in Australia. In Frost’s mind, it wasn’t quite like that. “That’s one of the things that I’m not mad about,” he said, carefully. Frost does not accept that his career was in decline in 1977, much less that he was primarily the light entertainer that the film suggests. “In fact, by that time I’d interviewed two or three presidents, two or three prime ministers, Moshe Dayan [the late Israeli Defence Minister], the Archbishop of Canterbury, a whole list of people. I had done a hell of a lot by then.”

All the same, the reporter tells us. “Frost is, mostly, delighted with the results,” and it is not hard to see why. He’s become a romantic hero of the media culture.

I have also heard it said that the film is either the better or the worse for the fact that it is seems to most people to be rather sympathetic to Richard Nixon, and that Mr Langella’s portrayal of “the disgraced president” gives him a humanity that rarely if ever emerged when “Tricky Dick” was still around in person. Such apologies (or damnations) miss the point, I think. Nixon’s humanity is strictly of the movie (or talk-show) sort, and it is an essential ingredient in making Frost, the media’s avatar, the film’s real hero. “You were a worthy adversary,” Mr Langella’s Nixon tells him, but it is really the media caricature of the ex-president, otherwise so ubiquitous, which has to be transformed into a worthy adversary for the media’s foreordained champion of their allegedly pugilistic encounter.

Of course, no such fictional gladiatorial contest could end without a voiceover summing up of the lessons, not of Watergate — we all know what those are — but of its translation into a TV entertainment, and here it is supplied by Mr Rockwell’s James Reston Jr. “You know,” he says,

the first and greatest sin of the deception of television is that it simplifies; it diminishes great, complex ideas, trenches of time; whole careers become reduced to a single snapshot. At first I couldn’t understand why Bob Zelnick was quite as euphoric as he was after the interviews, or why John Birt felt moved to strip naked and rush into the ocean to celebrate. But that was before I really understood the reductive power of the close-up, because David had succeeded on that final day, in getting for a fleeting moment what no investigative journalist, no state prosecutor, no judiciary committee or political enemy had managed to get; Richard Nixon’s face swollen and ravaged by loneliness, self-loathing and defeat. The rest of the project and its failings would not only be forgotten, they would totally cease to exist.

There may even be some truth in this way of looking at things, but it is a truth which depends on the supremacy of the television and celebrity culture that Mr Reston Jr. pretends to criticize. For what else is it possible for this culture to accomplish but the penetration of the veil of appearances to reveal the humanity beneath? The real point should be that this humanity is a matter of little interest to the “academics and political historians” who, according to the lovely Caroline, will treasure these broadcasts. Mr Morgan might have added that under no circumstances should this revelation be confused with a detail of any historical significance, but if he doesn’t add that caveat, I think we all know the reason why not.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.