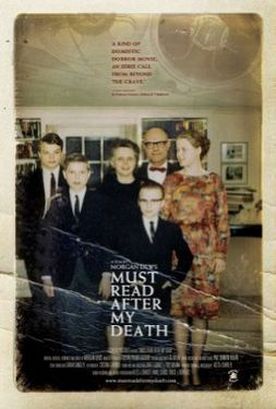

Must Read After My Death

I remember when I first heard the word “conformity” used as an abstract noun. I didn’t understand it then, and I don’t understand it now. Conformity to what? What is the opposite of conformity? Originality, I suppose. But who is truly original? We are all conforming to something or somebody. We could scarcely survive if we weren’t. Yet the cant term so often used to refer pejoratively to the dominant culture in America and the West during the 1950s has had a remarkably long and productive life as an inspiration to writers, artists and film-makers — people, in other words, who are unlike ordinary folk chiefly in their reverence for, even worship of, originality. Now, having reached the bottom of the cultural food-chain, the hatred of “conformity” has become the conventional wisdom of the media.

This is partly because the crusade against conformity makes a dramatic, easily graspable story with the individual as its hero, autonomy as his quest and “repressive” society as the villain.

Nature and nature’s way lay hid in night:

God said, “Let Kinsey be,” and all was light.

Or, for Kinsey, substitute Elvis or any of the other harbingers of the Great Awakening of the sexual and spiritual revolution, as so many in the media still see it, of the Age of Aquarius. And yet, there must also be some degree of insecurity about this implicit belief in the liberationist fairy tale, since the media go on repeating it endlessly. Of course, it also provides a justification for media’s worldview and the freedoms they enjoy to tear down the monuments of what we used to call “the establishment” once thought to be worthy of public veneration. That’s the reason for a movie like Revolutionary Road — which I didn’t see because I saw no reason to suppose it would differ appreciably in outlook from its director’s earlier American Beauty of 1999, a film which I loathed as I have few others in the nearly 19 years since I have taken up the reviewer’s pen.

Now, however, I have been caught unawares by a movie that could be the documentary counterpart to Revolutionary Road, American Beauty and all those other hit jobs on respectable, middle-class, suburban America before it learned, like the heroes of those films, to follow its bliss. The movie is called Must Read After My Death and has been made by Morgan Dews, who tells us that

The project started with a suitcase of 8mm films from my grandmother, Allis. One uncle sent me ten hours of dictaphone letters; his ex told me about a box of reel-to-reel diaries Allis had made for her psychiatrist. It was a friend, though, who ultimately told me about a file of tape transcripts and notes labeled Allis’s “Must Read After My Death” file.

Caught your interest? Relax. Allis’s dark secret is nothing — or at least not much — more remarkable than that she is a Betty Friedan-era housewife who has been persuaded by Betty Friedan or someone like her that doing as her neighbors do is somehow destructive to her personal essence, which must therefore be redeemed by massive doses of grandiose fantasy and self-pity. Or, as the press notes put it, Allis is “a modern woman at least a decade ahead of her time” because she “struggles against conformity, against the conventional roles of wife and mother.”

Does she indeed? In retrospect, this seems remarkably conformist of her. The one unusual and therefore perhaps, to Allis, shameful thing about her life is that she and her husband, Charley, seem to have been “swingers” well before “swinging” became sort-of fashionable in the ‘70s. Charley’s business took him to Australia for something close to a third of the year, and during his absences he wrote to her of his liaisons, actual or attempted, or included cryptic references to them on the audio tapes he sent which have now proved so useful for Mr Dews’s project. He seems to have had expectations of her doing the like and reporting back to him about it. Of what she did or how she felt about this, however, the movie has almost nothing to tell us.

Instead, we see Allis, Charley, and their children in home movies of the 1960s in which they look pretty much like any other family of the period. These images serve as counterpoint to the dark side of family life in some of Charley’s reports from Australia and Allis’s formulations of her grievances and anxieties for her therapists on audio tape. To me all this smacks so of the jargon and assumptions of the period as to be perfectly useless as a communication of anything real. Allis thinks Charley suffers from “a perfect inferiority complex,” for instance, because he is less educated than she, but that he needs “a woman with a capital W,” in which department she finds herself lacking. She doesn’t believe in conformity for conformity’s sake, it appears, and at times she feels like “the whole family’s committing suicide.” At one point she even says, “I understand people who kill their children” — but she doesn’t kill hers.

Why do all these inert emotions, expressed by a woman long dead in unoriginal language strike Mr Dews as something worth violating all his natural sense of reticence, discretion and loyalty to his family to bring to light? I suppose this is because, however familiar it has become to us, there is still money to be made and fame to be won in flogging the dead horse of 1950s-era suburbia. In the same way, there was for the generation of Allis and Charley’s parents and grandparents always a market for another hagiographical study of George Washington or Abraham Lincoln, or another heroic narrative on celluloid about the winning of the West. Audiences never got tired of those things either — at least until they did. I guess it’s just that the fashion for what people like to remember has changed.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.