Two Cultures in One

From The American SpectatorWriting in Vanity Fair’s March issue, Peter Bart, the editor of Variety, pronounces with all the authority of that august eminence that “the movie business is splitting into two distinct sectors, which have little if anything to do with each other.” The language there immediately brought to my mind a controversy which blew up in Britain half a century ago this year — which makes this an opportune moment to revisit it. This was the matter of the “Two Cultures,” brainchild of a Cambridge scientist called C.P. Snow who was also a popular middle-brow novelist, though his books have long since ceased to be read. He thought that the world of the arts and literature constituted one “culture,” the world of science and technology another, and that the two were, much to his dismay, growing ever further apart. The subtext of his remarks was really one of self-aggrandizement, since he obviously saw himself as the bridge between the two cultures.

Though his idea was savagely attacked at the time, most notably by F.R. Leavis, you can still see its traces in the writings of Richard Dawkins and his school of uppity scientists who imagine that their knowledge of nature’s mechanisms entitles them to pronounce authoritatively on theology and other subjects of which they have no knowledge. Like Snow, such people make the mistake of putting science and culture on all fours with each other when in fact they are opposites. Science is as certainly anti-cultural — except, of course, about its own culture — as culture is certainly, even when not actively anti-scientific, the dead weight against which science is always pulling. Culture, is backward looking, just as science is forward looking. Culture is history, the artifacts and stories which make up those “monuments of unaging intellect,” that were the solace of Yeats’s old age. There are no such monuments in science, which is progressive and anti-historical. All the monuments are aging, and most of them have been broken up and sold for scrap. The fundamental impulse of culture is to conserve the thought of the past; the fundamental impulse of science is to tear it down and rebuild it in corrected form.

But culture has changed since the days of Snow and Leavis, and the former’s self-puffery may have made some small contribution to our present form of anti-cultural culture which, perhaps envying the scientists their reputation and their vulgar certainties has joined them in wholeheartedly celebrating the progressivist principle. Increasingly, the traditional culture of art and literature has been drawn by popular entertainment into the realm of fantasy. Old ideas of love and honor that made literature and art go for centuries now must be transposed to outer space or some other fantasy realm — most recently in the alternative America of the 1980s represented in Watchmen — where they can do no harm, while the “real” world is reserved for political and therapeutic purposes.

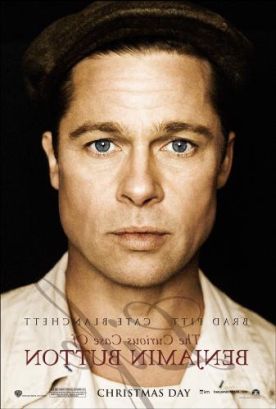

Which brings us back to Mr Bart’s “two sectors” of the movie business. The first of these is what he calls “tent-pole pictures” — I guess because the money they generate just about manages to hold in place the flimsiest sort of roof over the heads of the whole entertainment industry. These are the products of the major studios whose steady stream of movies pitched at the sensibility and intellect of early teens and based on comic books or video games, plus the merchandising rights thereto, allows them occasionally to spend $150 million on making a special-effects-laden movie like The Curious Case of Benjamin Button that no one wants to see. “In the tent-pole business, the concept is the star,” says Mr Bart — which is doubtless true so long as you stipulate that it is one star that can rarely if ever open a movie. Even Snakes on a Plane (2006) whose sky-high concept was contained in its title, only just about made back its production costs of $35,000,000 in domestic box office.

The other sector is the bargain-basement “art-house business” — though “art” doesn’t imply actual artistry. Rather, these are the “indies,” about which Mr Bart quotes an industry source as saying: “There will always be a dentist or a bored investment banker who’s willing to put up money for an indie film.” That makes the independent film sector sound like a weird collection of vanity projects — Benjamin Button without the budget — and, I must say, this is how it often appears to me. I can’t imagine how else a movie like last year’s Choke ever got made, for instance, so utterly charmless was it. Every now and then a good “art-house” indie, or what passes for it these days, like Little Miss Sunshine of 2006, will come along, but these are few and far between, and then they fall prey to hopeful imitators like Sunshine Cleaning by Christine Jeffs, which not only has “sunshine” in the title but also follows Little Miss Sunshine by casting the great Alan Arkin as a scandalous old man — as if that were a new iteration of the endlessly imitated superhero of the tent-pole pictures.

Others are stars’ vanity projects (Valkyrie and The Pink Panther 2 come to mind) or, like Milk, they get made because they have a ready-made constituency and/or they sport a political message so compelling in the eyes of the film and media culture that they don’t have to be commercial. These latter sort are the movies that tend to be nominated for Oscars, and three of the five best picture nominees this year fell into this category, Milk, Frost/Nixon and The Reader, all of whose domestic box office brought in less than it must have cost to make them. Kate Winslet finally won her Best Actress award for the last-named picture, but in the background was also the one for which she won the Golden Globe award six weeks earlier, Revolutionary Road, yet another box office loser which got the green light because of its conformity to assumptions about the narrative of 20th century history which are treasured by Hollywood and the media.

The fact that these assumptions are those both of the tent-polers and of the indies suggests that Mr Bart’s “two sectors” are almost as specious as Snow’s two cultures. Whether made for the masses or for the tasteful and discerning, the movie business, like the culture generally, relentlessly presents to us the progressivist’s world hinted at in Sean Penn’s acceptance speech for his Best Actor award for Milk, when he warned benighted folk like me who oppose gay marriage that our grandchildren were certain to be — such is the force of progress — ashamed of us. Presumably, they will look back on gran and gramps the way we now look back on the “repression” and “conformity” of traditional, “patriarchal” culture which produced the racism, sexism, homophobia, war, political corruption, bad music and massive unhappiness — for the middle class trapped in its strait-jacket as for the minorities it was oppressing — of the 1950s.

|

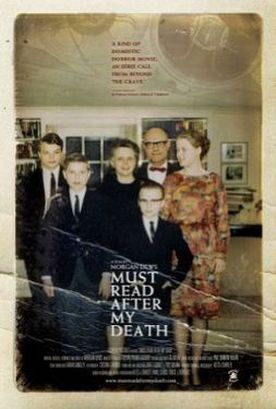

Make a movie of any sort, feature or documentary, showing how these social ills were triumphantly swept away by the various “liberations” of the 1960s and 1970s and your chances for an Oscar — or, if you’re not in the Oscar league, of finding a distributor — go way up. We love to hear the story. Or, if we don’t, we are decreasingly likely to hear any other. Just look at Must Read After My Death, a little documentary by Morgan Dews which opened in New York in February. A semi-biographical account of the director’s grandmother’s battles with unhappiness and family tension in the 1960s, the film practically fell into his lap when he uncovered a cache of home movies and audio recordings made by his grandparents, known only as Allis and Charley — at first to keep in touch during Charley’s long absences in Australia on business and later as an aid to what sound like some pretty intensive therapy sessions with an a couple of different psychiatrists and psychologists.

Charley is, as if instinctively obedient to the imperatives of the master narrative, imperiously and self-importantly patriarchal, while Allis is likewise near hysterical in her sense of desperation, as if she had been invented by Betty Friedan. There may have been contented housewives in the 1960s, but you won’t see documentaries being made about them. “I understand people who kill their children,” says Allis at one point, though she laments that she hasn’t got the guts to kill her own. And over this grim sound-track, we have the rival, visual narrative of the home movies which all present happy children at play and other typically home-movieish scenes from the 1960s. You don’t have to be a semiotician to “read” what this combination has to tell us, but the money quote comes when Allis says, “I don’t believe in conformity for conformity’s sake. I believe it is a wrong civilization and a wrong culture that requires you to conform before you can do anything.” But what if, as ours does, the culture believes that too?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.