Escaping Ideology

From The American Spectator“All art is to some extent propaganda,” claimed George Orwell, a view which was the corollary of his socialist belief that all human relationships had a political dimension. Though he himself was a robust conservative about some things — patriotism, for example — he was essentially conceding the magnificent artistic heritage of his country to a form of Leninist brutalism by which aesthetic judgment was subordinated to political. It was a concession that was also being made, implicitly if not explicitly, by artists themselves at more or less the same time all over Europe and America. This surrender to politics and, with it, utopianism is what is ultimately responsible for the decline of beauty in art so eloquently lamented in his new book, Beauty, by my colleague Roger Scruton. Beauty, like honor, demands consensus and is therefore in its essence non-political. No wonder art seems to have no further use for it.

Nowadays, even many conservatives have embraced political art, so long as the politics are — or can be construed to be — their own. This inversion of left-wing aesthetics holds that, especially in the popular arts, what is good and receives the critical seal of approval is what serves the counter-revolution. It’s hard to argue with that, but it is a view which obscures the essential truth that the revolutionary and the counter-revolutionary sides are not on all fours with each other. Wanting to politicize everything is not the same kind of enterprise as not wanting everything to be politicized — though of course the politicizers themselves deny this by begging the question. If, in other words, everything is political, then the denial that everything is political is also political.

I deny it! That’s why I always resist — not always successfully — getting involved in compiling lists of “the 50 greatest conservative movies,” for example. Since only conservatives deny the rights of ideology to filter representations of reality, the greatest conservative movies, or plays, novels, paintings, architectural or musical works, are those which allow you to take a holiday from being conservative — or liberal or anything else political — and put you back in touch with a (for once) non-political reality: the world as it really is and not as it must be supposed to be by the dictates of any ideology. Of course, in doing so, you have to ignore the ideologue’s charge that your supposedly non-ideological “reality” is ideological too. Reality for him does not exist apart from ideology. Hence, all art is to some extent propaganda.

Sometimes, I am inclined to think that conservative art in this sense is a hopeless case or that, like Professor Scruton’s Beauty, it has all but vanished out of the world of the popular culture. Then, suddenly, it pops up where it is least expected. I recently had occasion to go back and re-view La Femme Nikita (1990) by Luc Besson, the movie that, in my view, started the long process of development of the postmodern trope of the killer sexpot which culminated in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill movies of 2003-2004. At first Nikita seems to be propaganda because, like the later works of Quentin and the Taranteenies — including John Badham’s dire 1993 American remake of Nikita, Point of No Return (1993) — it warmly embraces the politically correct feminist view of human nature as essentially unisex — though I don’t suppose the feminists are all that happy about the erotic charge that both M. Besson and Mr Tarantino are obviously getting out of their examples of female empowerment.

Yet, going back to the former’s movie after almost twenty years, I realized that there is a subtlety to it that goes well beyond the ironies of the latter. Mr Tarantino, that is, is confined to his postmodernist playground, a Never-Never Land from which reality has been banished and in which both violence and sexiness are eternally filtered through other movies and comic books. Nikita, as the movie was called on its release in France, instead uses the violent and sexy idioms of the popular culture to shed some light on the idea of the feminine itself in a way that is profoundly subversive of feminist and unisex ideology. In this sense it is propaganda too, I suppose — anti-feminist propaganda. But there is also a sense in which being propaganda for organic and traditional ideas of human sex roles is not being propaganda at all. Rather, it is being anti-propaganda propaganda, as well as anti-feminist propaganda.

The story of Nikita was an updating of the Pygmalion myth. Nikita, played by the waif-like Anne Parillaud, was not a flower-seller, as in Shaw’s play or the Lerner & Lowe musical, My Fair Lady, that was based on it, but a Parisian street punk who murders a policeman in cold blood in the terrifyingly gory opening scene and is then taken into custody by the French secret service to be trained as a professional assassin, working for her country. The idea is of course as preposterously cartoonish and therefore postmodern as anything dreamed up by Mr Tarantino, and yet it redeems itself to an extent I would not have thought possible by the working out of its own postmodern premises in a rigorously realistic fashion. Say that such a thing could be, this is how it would turn out. Our heroine — just like a woman! — would fall for her mentor, in this case played by Tcheky Karyo, just as Eliza fell for Higgins, while he — just like a man — would fall in love as well, only more with the idea of his own creation than with poor Nikita herself.

The idea is almost mythic and not all that far from Shaw’s or Alan Jay Lerner’s, only instead of instruction in speech and deportment and ladylike behavior, this Galatea is instructed in the use of firearms and silent killing techniques. In the end, it doesn’t matter. Like Eliza Doolittle, Nikita remains all girl, her immersion in the hyper-male world of assassination and secret-agency — which, by the way, she is forced into and does not take up on her own initiative — only makes her more feminine, more vulnerable, more desirous of finding a man to cling to. The fact that she also becomes good at killing people comes to seem almost an irrelevance to the question of who she is in a way that it could never be for a man.

There is an eternal truth far beyond politics — at least for those of us who still suppose that anything is beyond politics — in this view of human nature, and even post-modernist art, which is normally taken up with trivialities and ironic borrowings from the art of the past, can express it. Or, rather, in expressing it such art immediately breaks through the self-imposed limitations of post-modernism to return to one or another of the earlier styles which tried to represent reality and not somebody else’s representation of it at two or three removes.

|

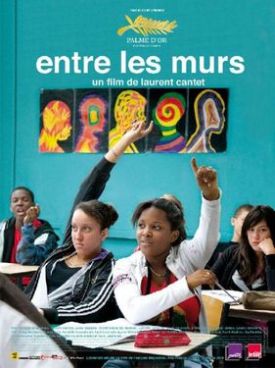

A more recent example, also from France where the pomo bug has not bitten so many or so severely as it has in the U.S., is The Class, winner of the Palme d’Or at last year’s Cannes festival and now on general release in this country. Directed by Laurent Cantet and based on a memoir, Entre les Murs, by François Bégaudeau — who also stars in the film — it is a documentary-style re-creation of the author’s experiences as a teacher in a multi-ethnic Parisian lycée. Like Nikita, the movie at first appears to conform to well-worn movie conventions, American as well as foreign — in this case conventions about what inner-city schools are like: dedicated teachers confronting tough, cynical, disturbed, even criminal pupils and reclaiming them, more or less, both for scholarship and society. I can’t imagine that it would have won at Cannes — according to Sean Penn, the chairman of the jury, “unanimously” — if audiences were not pre-disposed to see in it a reiteration of some such quasi-propagandistic “message” as that.

To my eye, however, Messrs. Cantet and Bégaudeau have blown that convention to smithereens and, with it, the liberal and multicultural ideology. What emerges instead is the reality of the liberal but useless good-intentions of the teacher and their inadequacy to bring about anything like the proper education of these uncomprehending pupils whom he has unwisely chosen to treat as equals. They are not monsters. They only learn from him to treat him and the culture he represents with the contempt that poisons the educational enterprise. As a result, there is a tragi-comic grace in this man’s reduction to helplessness and impotence: tragic because it makes such a dreadful contrast with the nobility of his and his liberal society’s aspirations and comic because neither he nor that society dares acknowledge his failure as such. As usual, ideology obscures reality — and it is the job of art not to promote some rival ideology but to clear ideology away in order to expose the reality beneath.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.