“John Had Nothing But Friends”

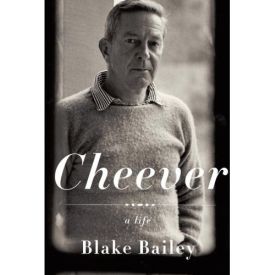

From The Washington TimesCheever, A Life

by Blake Bailey

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 774 pp., $35

Although I haven’t gone back and counted them, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that, of the words used to characterize John Cheever in Blake Bailey’s new biography of the man who liked to be called “America’s Chekhov”, “charm” and “charming” would be among the most frequently occurring.

On the opening page, Mr Bailey quotes Malcolm Cowley as saying: “John had nothing but friends.”

Yet, for all its virtues of readability, thoroughness and understanding of its subject, this biography’s portrait of John Cheever is not one characterized by its charm.

Rather the reverse, in fact. If my own experience is anything to go by, readers are likely to find that portrait more repellent than charming. Cheever emerges as needy, self-pitying, monstrously selfish, cold and even cruel to family and friends and at times a predatory homosexual.

And that’s not even counting the decades during which he was a sloppy alcoholic and a frequent embarrassment to those who loved him.

Yet it is hardly possible for a man to have enjoyed the success and esteem that Cheever did without the charm that Bailey, Cowley and many others insist he had. Why, then, do we not see more of this in his biography?

I think the answer must have to do with Mr Bailey’s choice, natural though it is, to base his work heavily on Cheever’s voluminous journals. He proudly asserts that he is one of probably only ten people in the world who has read every one of their 4300-odd pages — now available for public perusal at the Houghton Library at Harvard, though only a small portion of them have been published — and he is understandably eager to share with his readers the secrets he has gleaned from them.

Yet this decision gives the journals a weight they probably don’t deserve. Mr Bailey’s assumption has been in keeping with the assumptions of our therapeutic culture, namely that the thoughts of his subject’s heart, recorded in the journals, are somehow truer than the testimony of his novels or public utterances, or even than what is reported about him by those who knew him.

Of course, it helps that these reports are pretty obviously dominated by the more than twenty interviews he had with the author’s widow, Mary, who was far from being a disinterested witness. She seems to have been quite happy to concur with Mr Bailey’s acceptance of the lugubrious, self-pitying journal-John as the real Cheever.

On this model, charm and good manners, which Cheever must have possessed in abundance, at least when he was relatively sober, are mere surface matters and of little interest when compared to the secrets which he naturally reserved (for the most part) to his journal.

Yet what if the charming, the public Cheever, that kinder and better Cheever that he must have grown accustomed to superimposing, for appearances’ sake and when he was sober enough to do so, upon the night terrors recorded in journals written in the privacy of his study — what if that was the real Cheever?

As Bill Cosby once said, “What if the ‘real you’ is an a******?”

I know, I know. It hardly bears thinking upon. It is also true that, mostly thanks to drink, he certainly gave a lot of the people he was closest to in life, including his wife and children, a very close acquaintance with his non-charming side, even though for the last five years of his life — he died of cancer at 70, in 1982 — he was sober.

There is, to be sure, no definitive way of deciding between Mr Bailey’s therapeutic assumptions and those of bland suburban convention, but at least in the case of an author whose claim to biographization rests so heavily on his skill at dealing in bland suburban convention, the latter might at least have been tried.

Not that there is not lots of entertaining detail about the life of a man whose success was so largely owing to his ambiguous relationship with middle-class morality. The point is to avoid the trap, which Bailey does not always avoid, of a facile hunt for petty hypocrisies. Cheever himself does not always avoid it in his fiction, but in life he seems to have had a much larger range of sympathy with his neighbors’ as well as his own weaknesses.

I particularly liked his explanation of his lifelong habit of (Anglican-Episcopal) religious worship: “There has to be someone you thank for the party.” That very upper-middle-class, Anglo-American connection between good manners and the secrets of what Douglas Adams used to call “Life, the universe and everything” is no less striking for coming from someone who was so often, particularly under the influence of strong drink, himself unmannerly and even boorish.

Perhaps the ultimate test of true Cheeverism, if there is such a thing, is what ironic force one is inclined to give to the concluding passage of Bullet Park, and in particular the assurance that, after a crisis, “everything was as wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, wonderful as it had been.” Here’s what Blake Bailey says about it:

Now, if this be irony — and four “wonderful’s” would seem to suggest as much — then we must surmise that life is not wonderful in Bullet Park and never was, and besides Nailles still needs to take tranquilizers just to get through the day. So nothing has changed; but if that’s true, then what’s the point of the whole triumphant rescue? What, for that matter, is the point of the novel?

The problem here is too limited and mechanical an understanding of the way irony works. Yes, the wonderfuls certainly suggest irony, but irony does not mean that life is not wonderful in Bullet Park, only that one has to be aware of its wonderfulness in its natural context of not-wonderfulness.

All irony, in this sense, is an example of the “negative capability” that Keats attributed to Shakespeare, “that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.”

The same is true of Cheever himself, who was both wonderfully charming and charmingly (at least at more than a quarter of a century’s distance) horrible at the same time. That as much of this contradictory doubleness comes across as it does is a tribute to Mr Bailey’s biography, even though it leaves us wishing for more.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.