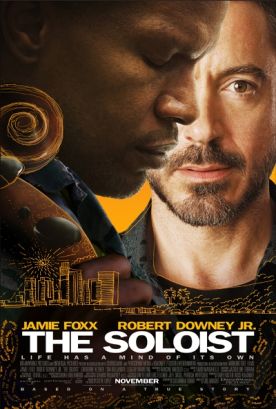

Soloist, The

From the British director Joe Wright (Atonement, Pride and Prejudice) comes The Soloist, an L.A. story based on real events that reflects the place rather better, perhaps, than its creators intended. Ostensibly, it is about a schizophrenic drop-out from the Juilliard School called Nathaniel Ayres (Jamie Foxx) who now lives on the streets of the City of Angels and occasionally gets a chance to play like one on a two-stringed violin or a donated ‘cello. But it will quickly become apparent to the viewer that the movie’s real focus is the glamorous newspaper columnist for the Los Angeles Times, Steve Lopez (Robert Downey Jr.), who “discovers” Mr Ayres (as they would have said back in the Golden Days of Hollywood), and attempts to make him into a media phenomenon, a brilliant but troubled star whom everyone wants to love — rather, come to think of it, like Robert Downey Jr. himself.

In other words, the movie is both about the publicity industry — on which the entertainment industry is now parasitic, rather than the other way around — and itself a product of that industry. For as it becomes clear that poor Mr Ayers is going to remain locked in his private mental world, so it also emerges that our sympathetic feelings are really owed to Steve Lopez, whose own bid for stardom comes in the guise of his sad story about how he has been unable to confer stardom on Nathaniel. The latter’s delusions remain as potent at the end of the picture (and, apparently, in real life) as they were at the beginning, in spite of his having been enticed indoors and under a roof in the interim. Thus the crazy homeless person turns out not to have much of a story after all, but he does serve as a catalyst for various things happening in what the film-makers see as the much more compelling narrative of the life of Steve Lopez.

The main thing that happens to Steve is of course that, like both his schizophrenic protégé and the newspaper business that employs him, he suffers. Now there’s a surprise! He suffers from the film’s opening sequence when he falls off his bike and incurs superficial but picturesque injuries to his face, until the end, when he is forced to conclude that there is nothing he can do for Nathaniel apart from being his friend — which is cause enough, along with the suffering, for self-congratulation. When Steve first meets Nathaniel he notices how the homeless man has been scarred by his hard life on the streets, whereupon he points to the wounds on his face and says, “Me too.” It’s a perfect summary, in miniature, of what the movie is about: the immense, and immensely self-satisfying, compassion of Mr Downey’s Steve all but crowds out of the picture the things he is supposed to be compassionate about.

“I’m not comfortable being your god,” he says at one point to the (temporarily) worshipful Mr Ayers. You or I might not be able to utter a line like that with a straight face, but for Mr Downey it sort of goes with the territory. It’s all part of his being a suffering servant. Scenes in which he tries, mostly ineffectually, to help Nathaniel are interspersed with scenes illustrating all the trouble in his life, both domestic and professional. We are especially to regret the decline of the newspaper generally and of the Times in particular, which is visually brought home to us with shots of Mr Lopez writing furiously as his laid-off colleagues carry the contents of their desks in boxes out of the Times building. All this is going on in the midst of depressing allusions to events of the middle period of the eight-year Bush administration — Iraq, Katrina, and a sardonic mention of Governor Schwarzenegger — and at the same time that he is trying to mend relations with his estranged wife, played by Catherine Keener. She is suffering, too, by the way.

There is a third type of scene, too, which attempts to find visual analogues of the music, mostly Beethoven, that Nathaniel loves. The favored metaphor seems to be one of soaring flight — either of birds or, I guess, the flying cameras which produce those striking overhead shots of the L.A. freeways in all their geometric splendor. Mr Wright also — injudiciously, I think — makes use of some ‘60s-style psychedelic imagery that accompanies a rehearsal by the L.A. Philharmonic of Beethoven’s “Eroica” symphony. These images seem to be mostly for the benefit of the audience, rather than an attempt to convey how Nathaniel experiences the music. The workings of his broken mind remain too obscure for that. But Steve obviously feels the nobility of Beethoven as we are meant to do along with him.

At one point, Steve observes: “The story of a guy not showing up is not a story.” I can’t help thinking that the movie should have taken a caution from this undeniable truth. Nathaniel doesn’t show up, at least not as a person we can avoid pitying and so take a properly sympathetic interest in. And the attempt to put Steve Lopez in his place just comes across as yet another bit of media self-absorption and self-importance. Just showing up is not enough to make an interesting story either, for that matter, though as Woody Allen observed most of life consists of it. The film’s key line comes with Steve’s recognition that “You’re never going to cure Nathaniel; just be his friend and show up.” That may make him feel good, but it doesn’t do much for a movie audience at too great a distance from the action to take much vicarious satisfaction in it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.