Irony Without Irony

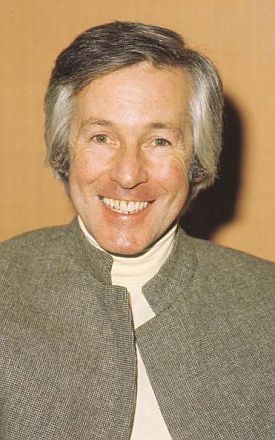

From The American SpectatorChaucer’s Knight — the non-ironic version

When my oldest son was a Boy Scout in England 20 years ago, I once watched his troop play a game in which the boys formed a circle around a troop leader holding a soccer ball. The leader proceeded to throw the ball to the boys at random, saying as he did so either “head” or “catch.” If he said “head,” the boy was supposed to catch it; if he said “catch,” the boy was supposed to head it. Anyone who slipped up and caught the ball when instructed to catch it or head the ball when instructed to head it, was out and had to leave the circle. Eventually, only one scout was left standing. That boy, as I have often had occasion to think since, must have been one of nature’s ironists. He and the others had certainly had an education in the central principle of all ironic — and, for that matter, non-ironic — discourse, namely that meaning depends on context. A boy who’d said that he would just love to play such a game could have meant either that he’d love to play it or that he’d absolutely hate it, and all but the most literal-minded would have been able to tell which it was on hearing the words spoken in their context.

The ability to read that context, to pick up the cues indicating irony or its absence, depends on a certain degree of social skill and experience in complex social interactions. Irony, that is, belongs to the world of face-to-face communication, even when we encounter it in a book or a movie. If we are able to recognize the irony in fictional contexts it is because we have previously experienced it, or something like it, in real ones. Maybe that’s why, as we have begun to spend more and more of our time interacting with each other remotely and electronically, rather than face-to-face, it seems that our irony-reading skills have tended to atrophy, or else to go haywire, producing, on the one hand, a leaden literalism or, on the other, the sort of paranoia which supposes that everything must mean something other than what it says.

The latter is the world of the post-modern critic, that master-figure of the popular culture, in which everything is assumed to be ironic. It is what makes possible the endless “re-boots” — as they are now called — of cartoon and movie franchises, such as this spring’s of Star Trek and X-Men. The fans of both have always been ironists, and so they are naturally open to new “readings” of these classics. In fact they delight in them. If you were never the victim of the na ve illusion that Captain James T. Kirk was a real person in the first place, you are unlikely to mind that he has become yet another simulacrum of a person. But — call me crazy — I keep looking for signs of the culture’s reaction against ironical excess.

Ten years ago, a young man named Jedediah Purdy, then still in his twenties and home-schooled by hippies in West Virginia, wrote a book titled For Common Things that was an attack on the ironic culture as he saw it then — before there was any Daily Show or Colbert Report and nothing worse than David Letterman or “Seinfeld” to give irony a bad name. Ironically, the anti-irony screed enjoyed a certain vogue. The New York Times at its most po-faced published an interview that treated this backwoodsman and recent Harvard graduate as a reincarnation of H.D. Thoreau, or perhaps a sort of humorless version of Abraham Lincoln, destined for greatness by his call for a return to what he imagined were the rustic simplicities of our forefathers.

Of all the silly things to be against, irony must be among the silliest. It is like being against algebra. Irony is simply a rationalization of the way the world — in this case the rhetorical world — works, and has always worked. But people could sympathize with the sort of social insecurity that must have lain behind Mr Purdy’s attachment to puritanical plain-speaking, and, with the help of The New York Times, the book made enough of a splash that that gentleman, now a law professor at Duke University, has lately written another, even sillier book. It is called A Tolerable Anarchy and is a tract on behalf of liberal utopianism. I see it as a sort of sequel, which must have grown out of the earlier book’s implied preference for humanity in the abstract rather than all its confusing imperfections.

Two decades before his denunciation of irony and a few years before my son was inducted into the scouts, Terry Jones of Monty Python fame, a champion ironist who was also a part-time medievalist, wrote a book called Chaucer’s Knight: The Portrait of a Medieval Mercenary, which purported to show that the man described in the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales as a parfit gentil knight was in fact a brutal and cold-blood killer with nothing chivalric about him. In fact, Mr Jones was pretty sure that there was nothing chivalric about medieval chivalry itself. The arguments over his detailed evidence for this shocking proposition have gone on for nearly three decades without anyone’s thinking to ask what would have been the point of Chaucer’s encoding the truth about his knight so successfully that it took some six centuries for a TV comedian to decode it?

But then, in the lit crit biz as it is practised today, such questions simply don’t arise. Irony is pretty much self-justifying and, without it, the whole edifice of literary scholarship would come crashing to the ground. In a recent issue of The Chronicle of Higher Education, an English professor at the University of Virginia admitted as much in the course of a quixotic call for a moratorium on “readings” — that is, the critical application of one of the many proprietary keys (“Marx’s, Freud’s, Foucault’s, Derrida’s, or whoever’s,” as he put it) designed to unlock the infinite number of ironic meanings of a text which could not have been intended by its author. I wonder if this poor sap can realize how much the very well-entrenched cultural phenomenon known as post-modernism, which extends well beyond academia and into popular entertainment, depends on the existing gentleman’s agreement among critics to honor any ironic scrip as legal tender? Literary scholarship first became a sort of Oklahoma land rush in which a horde of fledgling intellectuals, bent on obtaining tenure against fierce competition, sought to stake out their little ironic territory wherein they alone might be supposed to know what this or that monument of Western civilization really meant — or at least could be made to mean. Now that every blogger on the internet can take part too, I don’t think we’re going to be giving up the “readings” game, even temporarily, anytime soon.

Besides, the “texts” that are subject to ironic reinterpretation now include the documents on which our government is founded. Every judge is now an ironist, seeking new meanings in old documents by which some progressive fad — the latest is gay “marriage” — can be shown to be not only justified but mandatory. President Obama has lately told us that a pack of legal ironists headed by his attorney general are also to be turned loose on the so-called “torture-memos” written by officials of his predecessor’s administration so as to find in them some way for their authors to be prosecuted as criminals. Already, the George W. Bush administration has been the subject of more ironic re-interpretation than any in our history, including that of Terry Jones in Terry Jones’s War on the War on Terror (2004).

Well, why believe the President of the United States when you’ve got the finely-tuned paranoia of Terry Jones’s — or Frank Rich’s or Maureen Dowd’s or Eric Holder’s or whoever’s — “reading” of him to go by? Still, you’ve got to think that even the po-mo critic, must sometimes get weary of such a soul-deadening exercise, set up on the premiss that nobody but he knows what anybody or anything is really about. That may be why, in Romeo Castellucci’s recent staging of Dante’s Inferno in London, hell was represented between a pair of out-sized quotation marks as the seat of irony, where a Satanic Andy Warhol went about with a Polaroid camera, snapping photos of the damned. It is, as Dominic Cavendish noted in the Daily Telegraph, “a vision of unremediable human loneliness.” Likewise, a staging of Beowulf in New York had the legendary hero, in the shape of the nerdy-looking author, Jason Craig, confronting three academic critics in the place of the monsters of the poem. Of course, that was itself meant to be an ironic joke, but I detect in it a further ironic subtext of desire to leave the circle of the ironically clued-up, at least for a moment, in order to breathe a purer air.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.