Reality and the Postmodern Wink

From The New Atlantis, Winter, 2009The street I have lived on for seventeen years is suddenly alive with children. It is quite a delightful place to be nowadays. When I moved here, I don’t believe there was a child on the block apart from my own, who were there only in the summers and on holidays. Now there must be dozens of them, most not yet of school age. Last Halloween, I noticed how many of my neighbors who are young parents accompanied their little ones on their trick-or-treating rounds while themselves dressed up as witches or pirates. I take it this is a manifestation of the “parenting” craze. A word that didn’t exist when I was a young parent — still less when I was the child of young parents — is now used to describe that mode of child-rearing that begins with the reform of the adult to be more child-like rather than, as in generations past, the child to be more adult-like. Mom and dad now involve themselves in their children’s pastimes out of a supposed duty of empathy that is somehow continuous with responsibility for their children’s safety and well-being.

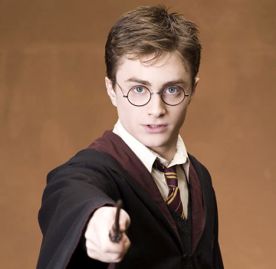

I’m sure that there is much that is good about the new parenting, and it must be rather thrilling for the children, at least in their early years. Yet I can’t but see a disquieting connection to the infantilization of the popular culture and the phenomenon of the “kidult” or “adultescent” who dresses in t-shirts and shorts, slurps up fast food, watches superhero movies, and plays video games well into his thirties or even forties. It’s true that there have been for more than a century certain protected areas of childish innocence where Santa Claus or the Tooth Fairy or whatnot have been suffered to remain undisturbed, for a time, by adult consciousness. But this demesne has expanded to include much new territory — like Harry Potter and Batman, who provided so many of the costume themes for Halloween last year — and to encroach on ever more of what once would be considered adulthood. Mom and dad must be intimately involved in their children’s fantasy world not only out of duty to the children but because it is, increasingly, their world too.

If this is more disturbing to me than to most people, it may have something to do with the fact that I have been a movie critic for the past eighteen years, during which time I have gone to the movies, on average, two or three times a week. My distinct impression is that there are fewer grown-ups going to the movies with each passing year. Nowadays the cineplexes are overwhelmingly the haunt of young teenagers — adults wait for movies to come out on DVD — which helps explain why so many movies are so obviously made with that childish demographic in mind. And with the triumph of the children’s fantasy picture as the dominant genre of our time, there has been a corresponding revolution in the standards and practices, as well as the basic assumptions, of the critical fraternity to which I belong.

For several years, I reviewed movies every week for the now-defunct New York Sun. During the time I was there, I must have criticized a great many movies for their lack of verisimilitude, and my editors either agreed with or tolerated my ever-more-crotchety critical stance. But finally, in late 2007, I submitted such a review of a film—Kirsten Sheridan’s impossibly soppy August Rush — which obviously pushed a new, younger editor to the limit. “Of course it’s fake,” he wrote to me in obvious exasperation. “It’s a movie!”

Maybe he thought that I thought this movie, or any movie, was or should have been a faithful photographic record of things that had actually happened in that world which we increasingly often have to qualify as “real,” but I doubt it. More likely he was simply noticing that to say that a movie or any other work of ostensibly representative art bore no resemblance to reality is no longer a legitimate critical response — no more to the cinematic version of “magical realism” that informed August Rush than to the conventions of the superhero movies that account for such a large share of this and every year’s box-office receipts. Neither the critical nor the artistic fraternity any longer has the self-confidence to pronounce on the distinction between real and unreal. Both have lost their license as reality-hunters. The editor at the Sun was just reminding me that we are all postmodernists now. Under the circumstances, I could hardly fail to wonder if my forlorn clinging to an undoubtedly outdated aesthetic standard was just a sign of age. Can it be mere coincidence that this happened in my sixtieth year?

Around the same time, I noticed that a blogger who describes himself as “The Whining Schoolboy” had quoted something of mine while describing me as “the wonderful, and curmudgeonly, media critic James Bowman.” I’m grateful for the “wonderful,” of course, but I’m not one hundred percent sure how I feel about the “curmudgeonly.” This is because I’m afraid the description may be accurate. As a film critic, I could hardly fail to notice that, with each passing year, there were fewer and fewer movies I liked. The last time I had to compile a top-ten list for the year — I think it was in 2003 — I had to struggle to think of ten movies that I had liked not just well enough for the accolade but at all. After that, the paper quietly retired the top-ten list. Was it the movies that were getting worse or was it my crotchety old man’s inability to appreciate them? The same doubts assailed me when I wrote what I thought was a light-hearted satirical piece ridiculing the New York Times’s Arts pages for treating video games on a level with movies and plays. Various young people wrote, in a spirit of charity, to tell me that, actually, video games should be treated as works of art, and that there is a real aesthetic and moral seriousness to the best of them, at least.

I am beginning to understand that I just don’t see things the way younger people do, but I don’t think that this is because I am out of touch. Or not just because I am out of touch. Rather, it is because a cultural expectation that could be taken for granted when I was a young man — namely, that the popular movies I loved were trying to look like reality and could therefore be judged on the basis of how successful or unsuccessful they were in approximating reality’s look and feel — has unobtrusively dropped out of the culture which has shaped the sensibility of young people today. Their formative visual experiences were not, as mine were, John Wayne Westerns and war movies. They were comic books and hokey TV shows, the shadow of whose hokeyness was cast backwards, as it were, on the John Wayne movies. Not that we didn’t have comic books and hokey TV shows in the 1950s and 60s, but we had some perspective on them provided by a popular art form that strove to be taken seriously. The triumph of the superheroes in the 1970s helped to establish a new consensus that heroism itself was mere artifice and therefore to be judged by aesthetic rather than moral standards.

Aging Art

In a piece he recently wrote for The Times of London, the philosopher Roger Scruton, who is a few years older than I, compared his experience with the works of the painter Mark Rothko when he first encountered them in 1961 and when he recently revisited them in a new exhibition that opened in September 2008, in the Tate Modern gallery in London. Back in 1961, he writes, Rothko’s paintings

spoke of an other-worldly tranquility; looking into them your eyes met only depth and peace. For an hour I was lost in those paintings, not able to find words for what I saw in them, but experiencing it as a vision of transcendence. I went out into the street refreshed and rejoicing, and would visit the gallery every day until the exhibition closed…. Revisiting his work today my first desire is to ignore the critical sycophancy lavished upon him, and to ask if there is anything there. Are these uniformed canvases the angelic visions I thought I saw on that summer evening half a century ago? Or are they the routine product of a mind set in melancholy repetitiveness, as empty and uninspired as the pop art that Rothko (to his credit) was at the time denouncing?

I think Professor Scruton is right to recognize that these are not the only two alternatives, and that there may be moments of beauty and transcendence that depend entirely on the moment, either historical or personal, when one experiences them. Such moments are, like religious revelation but unlike scientific experiments, essentially unrepeatable. Yet we also expect art to have something of the consistency and reliability of natural phenomena: if the magic doesn’t reliably work, it must be unreal, an idiosyncratically subjective and fleetingly emotional response with no critical standing. Professor Scruton continues, writing that

something in me wants to remain true to my adolescent vision. The beauty I imagined I also saw, and could not have seen without Rothko’s aid. But I do not see it today, and wonder how much it was the product of the stress of adolescence, and of the strange, still atmosphere of the Whitechapel Gallery in those days when so few people visited it, and when those few were all in search of redemption from the world outside. Now that modern art has been cheapened and mass- produced, to become part of that outside world of commercial titillation, it is harder to see Rothko as I saw him then.

|

To some extent this dilemma is an artifact of modernism itself, whose most salient characteristics are the feeling of liberation from traditional restraints and the exaltation of the artist at the expense of his subject. Both things have by their nature a relatively brief shelf life in the aesthetic marketplace. After the modernist revolution around the turn of the twentieth century, it only took a couple of generations before both freedom and the phenomenon of the artist-hero could be taken for granted. Nobody cares about the traditional restraints anymore or remembers when anyone but the artist was the hero of his own creation. Though the culture is still committed to these once-revolutionary doctrines, the thrill of the revolution itself is long past.

That’s why, I think, the world of popular music and rap, which grew up in the shadow of modernism, must keep stoking the fires of a factitious anger and resentment against “the system” or an authority that has long since ceased to impose any meaningful restraints upon either the musicians themselves or their young audience. They go on reenacting, as a kind of ritual of their po-mo, pretend world, the rebellion which once liberated them (even before they were born), long after there has ceased to be anything much to be liberated from. Revolutionary gestures and iconography take the place of actual revolution or rebellion, because those who make them have similarly lost confidence in their ability to interact meaningfully with reality.

I don’t know if it was the loss of his youthful revolutionary fervor which accounted for Roger Scruton’s disappointment with Rothko forty-seven years on, but I don’t think anything like that can be the cause of my dislike of August Rush — and most other movies produced in the last decade or two. For one thing, I never had very much in the way of revolutionary fervor even when very young. I never carried any grudge against authority or “the older generation,” and, though not immune to the charms of the modernist movement, I always preferred what had gone before it — Dickens to Joyce, Keats or Tennyson to Eliot or Pound, Brahms to Stravinsky, Turner to Picasso.

Once that didn’t matter, since many of the early modernists were themselves believers in tradition and saw many kinds of continuity between themselves and their predecessors, if not of the Victorian age then of some earlier period. Eliot, for instance, was an admirer of John Donne and other “metaphysical” poets from the days before what he called the “dissociation of sensibility” of the seventeenth century. Like so many artistic revolutionaries before him, he saw himself as refurbishing and restoring a previous aesthetic standard that had fallen on hard times. Above all, the modernists were reluctant to cut themselves loose from the history of the Western mimetic tradition, which evolved over centuries out of primitive myth and legend and at both “high” and “low” stylistic levels. In his 1946 book Mimesis, Erich Auerbach took examples from ancient, medieval, and modern literatures, traversing half a dozen European languages and three thousand years of history and including not-obviously-realistic works from Homer’s Odyssey to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, all in support of his thesis that the Western tradition in literature is distinguished by its fidelity to a reality that could still, as late as 1946, be taken for granted.

Now, however, the tendency of both art and criticism is to debunk the claims to “truth” or “realism” of the old-timers. Their achievement has to be measured not in relation to the external world but to some critical construct or “theory” which has been thoughtfully provided by the critic for the purpose. Thus the hero of the postmodernists is not the artist (as it was for the modernists and, before them, the Romantics) but the critic. By harking back to an outmoded standard of criticism based on verisimilitude, I am in effect guilty of an act of l se-majesté against the dignity of the critic-hero who relies on his own ingenuity — and his politically- developed conscience — to supply a much more satisfactory if entirely imaginary context within which not only movies but all the phenomena and epiphenomena of the pop-cultural world up to and including political discourse can be judged. My clinging to outmoded standards must doubtless have something to do with my age and my temperamental conservatism, but it also has a lot to do with a way of seeing that the culture has long assumed people need to be educated out of if they are properly to understand and appreciate the riches that the postmodern culture has to offer. That culture’s insistence that I see things its way is what I am resisting.

Looking Real

When I go to the movies, I always try to sit a little to one side of the screen. In the usual two-aisle seating configuration — or what used to be usual until stadium seating became ubiquitous — I usually sit just to the right side of the right aisle, about halfway back. I’ve never thought much about why I do this, but if I had to guess I would say it is to give myself a little perspective — something I am particularly in need of when I have to write about the movie I am seeing. Go up high enough with the stadium seating, and you can achieve a similar effect, in that case by looking down on those who would otherwise be — as they always have been throughout the history of the cinema — looked up to as, literally, “larger than life.” I know that I need this perspective because I am so liable to get hooked by the images on the screen, so ready to believe in the reality of what I am seeing there, that I need to remind myself that “it’s only a movie.”

A great many people over the years have said and written those words to me when they have supposed me to be too eager to find the hidden and unregarded significances in what I have seen in a picture. Little have this critic’s critics realized how I need their reminders — not because I read too much into the movies, as they suppose, but because I am still at heart what might be called a na ve viewer of them: someone who is predisposed to cling to the illusion that what I am seeing is real. This experience is a big part of what I have always loved the movies for, so that when a director doesn’t bother even to try to make his movie look like real life, it strikes me not just as an annoyance, spoiling an important part of my pleasure, but almost as an insult.

Of course, it is a lot harder to make it look like reality when your subjects are space aliens or other unworldly creatures, humanoid robots, or talking animals. That’s why, to my eye anyway, the recent film adaptations of the fables of J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis have been less than successful. What can be accepted as being within the bounds of verisimilitude on the page often cannot be accepted on the big screen, where talking animals, like superheroes, instantly proclaim their own cartoonishness. And cartoons are in their turn instantly recognizable as belonging to a genre apart, and with only the most tenuous connection to reality. This is not to say that the portrayal of historic, real-life events cannot be cartoonish. Tomas Alfredson’s 2008 vampire movie Let the Right One In did a fine job of presenting its vampire heroine, played by Lina Leandersson, as a natural part of childhood’s sense of enchantment, whereas the 2006 movie 300, Zack Snyder’s account of the Battle of Thermopylae, went out of its way to make a live-action portrayal of real-life heroes look like a cartoon — as, indeed, the film was based on a comic book.

In other words, we don’t need to be literal-minded in our demand for cinematic realism. There are lots of ways to make things look real, and a movie like Harold Ramis’s Groundhog Day (1993), which takes place in a parallel universe where time as we understand it has no meaning, actually manages to look more like reality than reality. That is the mark of true artistic success in any medium, perhaps especially in the movies. It was even, in my view, quite common in the movies until their makers learned, first from the modernists and then from the postmodernists, the stylistic tic of reminding the audience of the work’s artifice and so inviting the audience to enjoy what amounts to a gigantic in-joke. I don’t believe it to be an accident that this sort of playful, non- functional irony, which is the hallmark of the postmodern, has become more common as the movie industry has become more and more geared to producing movies for children.

I understand that part of the reason directors do this is because young people are what we nowadays call “media savvy” and are proud enough of the fact that they like to be reminded of it. We know that you know that it’s fake, the filmmakers say, so we’re not going to go through the silly, old-fashioned charade of pretending it’s real. But, see, I still, for at least a little while, don’t know it’s fake. I want to believe — which, I suppose, makes me more kid-like than the prematurely sophisticated kids who are all so media savvy that they don’t take it personally when the author assumes they know it’s fake. They do know it, too; for them, there’s no illusion to be shattered anymore, so they are disinclined to treat the frankly unbelievable and unbelieved images with very much respect, whereas I still have a child-like faith in them and so feel annoyed and insulted when the filmmaker pays me the compliment, as he supposes it to be, of assuming that I know it is all unreal.

A variation on the “it’s-only-a-movie” theme comes in the form of the e-mails I often get which include a sentence that reads something like this: “Why can’t you ever just go to a movie for escapist enjoyment?” This notion of “escapism” seems to be accepted by everyone almost as the reason for the movies’ existence in the first place. Read any history of the medium and it will tell you that Depression-era Americans went to see the lavish movie musicals of Busby Berkeley and similar glamorous stuff to escape from the bitter hardships of their daily lives. Reality was getting them down, so they sought out a fantasy. I don’t believe it. Speaking as a na ve viewer of the sort that is supposed to have a taste for escapism, I feel quite sure that what those audiences wanted from the pictures was not escape from what they thought of as the real world but a cinematic reality that they could regard as superior to it and that was therefore more real than the world outside it. To us it may look as if poverty and failure were the reality and love and happiness mere fantasies, but I don’t think it looked that way at the time.

If it hadn’t already been taken over by a bunch of Dadaist pranksters in the 1920s and 30s, another word for the psychological effect of the movie image might be “surreal” — particularly as it might be applied to the early horror films which were contemporaneous with the surrealists. The trouble was that, once the trick had been performed, it wasn’t very horrifying anymore. We knew how it was done, and if we saw the films again we enjoyed them in a spirit of self- congratulation. What we were really enjoying was the spectacle of that na ve viewer who was once ourselves — or, nowadays, more likely our grandparents — still being taken in by the illusion we have learned to see through.

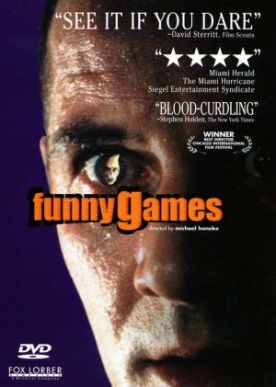

Postmodern, Postmoral

This is the characteristic mode of movie-watching in the postmodern era. Compared to the days when people went to the pictures once a week, so much of our lives today is lived among artificial and second-hand moving imagery on screens large and small that filmmakers often prefer to concede in advance that they can no longer expect even a first-run suspension of disbelief on the part of their increasingly youthful audiences. In short, there is a severe shortage of willingly na ve viewers like me, and they are almost nonexistent among those under thirty. That’s why horror movies are nowadays so often comic rather than scary — like Wes Craven’s Scream (1996) and its sequels and the Scary Movie franchise. The illusion is exposed even before it is created. And those movies that continue to try to scare us — Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) is a good example — must do so by deliberately subverting the narrative conventions of the movies, including that by which horror was once finally contained and neutralized by the forces of good, which thereby proved to be more real, after all, than the surrealities. That, too, is a trick that can only be performed once, as perhaps the failure of Mr. Haneke’s attempt at a remake, in English, ten years later showed.

|

The point is that what scares us about such a film is not so much the acts of violence which it represents as the feeling of being lost among them without any moral compass. The familiar movie conventions of the home-invasion picture, some of them anyway, are still there in this film, but they all mean something different. That seems appropriate, somehow, since its criminals are portrayed as having no motivations for their acts of cruelty and horror but simply the pleasure of committing them. That may sound like the familiar Hollywood phenomenon of the serial killer, which is similarly based on the premise that unmotivated criminality, attributable only to some obscure psychosexual meltdown, is a lot scarier than the usual kind. But the Hollywood serial killer is insulated from the full horror of his deeds by such a Gothic excess of blood- curdling evil that it tips over into comedy, as in the case of his prototype, Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Mr. Haneke’s serial killers refuse to take themselves even a little bit seriously.

And so, as the horror begins to dawn on us amid scenes of everyday domesticity, the director intrudes himself into his movie. The dominant of the two young killers (Arno Frisch) turns to the camera and winks at us. Later, when he is offering to bet with the horrified family members as to whether or not they will be alive in the morning, he turns to the camera again and, shockingly, addresses us, the audience. “What do you think?” he says. “Do you think they have a chance of winning? You’re on their side, aren’t you?” Later when Anna, the mother played by Susanne Lothar without any apparent consciousness of being in a movie rather than the most horrifying experience of her life, says that their cruelty has gone far enough, the young man says to her: “You think that’s enough? We’re not up to feature film length yet.” And again he turns to the camera. “Is that enough? But you want a real ending, with plausible plot development, don’t you?”

Most memorably and bewilderingly, when Anna manages to snatch a momentarily unattended shotgun and shoot the second young man (Frank Giering), the first screams: “Where’s the remote?” and, finding it, rewinds the whole scene to the point before she seized the gun and prevents her, the second time through, from getting it. The funny games that the young men are playing with the family are echoed by the funny games Mr. Haneke is playing with us. During their final murder, the young men are shown discussing a science fiction movie — presumably Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) — in which, they say, the hero’s family is in reality and he’s in fiction. Here it is obviously the family that is in the fiction and the heroes in a kind of reality — the movie-reality, that is, which the director assumes the right to create, and to let us know he is creating.

And this is the point of his characters’ taking the audience into their confidence, for it reinforces the central thesis of the film that there is no moral order in any other (any real) reality, that makes any difference to what happens in this film. We all make our own reality, just like the movie director, just like his monstrous protagonists in toying with the terrorized family, and there is nothing either you or the universe—which you may still have allowed yourself to suppose cares about what happens to you—can do about it. “You’re on their side, aren’t you?” asks the killer. But he knows that the filmmaker, who stands in for God in the context of his movie, is taking his side, not theirs, as you may also find yourselves surprised to expect him to do the way the old movies did. We are in the hands of the filmmaker, and the filmic reality he creates, which is the only reality that matters or is at all persuasive to the postmodern audience.

Curmudgeonliness No Cynicism

I have gone on at such length about Funny Games because I think it is a demonstration of our cultural assumptions about what reality is — a sort of self-chosen Sartrean sandbox for us to play in just because there is nothing else — and what the implications of those assumptions are, not just for movies but for art in general. For the mimetic function that I so value in the movies as in other arts is pointless if there is no God — no real God — and the universe has no moral order. Why would anyone want to imitate or replicate — or to watch an imitation or replication — of mere chaos? The recourse to fantasy or whimsy is both an act of despair and an attempt to cover it up with brittle laughter. Mr. Haneke’s film exposes the charade, the postmodern funny game, in a uniquely horrifying way — which is why, I take it, he is reported to have said that if the film was a hit it would be because the audience hadn’t understood it.

Meanwhile, I admit to being a curmudgeon. But curmudgeons can sometimes be right too, just as paranoiacs can have real enemies. Moreover, such curmudgeonliness as is required to resist today’s easy acceptance of fantasy as the characteristic mode of a fundamentally realistic medium is the opposite of cynicism. The cynics are the prematurely aged children who have been taught by the culture to believe that all the enchantment the movies are capable of generating is a fake, though none the worse for that, and to congratulate themselves for “getting” it instead of losing themselves — and so reclaiming their capacity for belief — in the fantasy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.