Let The Sky Fall

From The New CriterionOld-Fashioned

On my way to the dentist in the middle of the day not long ago, I heard Philip Reeves — a Briton, by the sound of him — on National Public Radio interviewing an Indian gentleman whose name I didn’t catch about the terrorist massacre in the latter’s country last Thanksgiving-tide. The Indian spoke English with the sort of aristocratic British accent that you never hear in Britain anymore. Even the Queen doesn’t speak so “posh.” He was saying that for anyone born and raised, as he was, in Bombay, the sight of the slaughter at the Victoria railway terminus there was particularly traumatic. Now the English-speaking Western media had, in the wake of the disaster, allowed an occasional mention of the Victoria terminus because its Indian name, Chhatrapati Shivaji (after a 17th century Maratha champion of the Hindus against the Mughals) is practically unpronounceable. But Mr Reeves seemed annoyed by the Indian’s comments and took them up with an insistent mention of the feelings in Mumbai or — as he added with a peevish reference back to his interlocutor — “‘Bombay,’ as he calls it. . .”

Bombay, indeed, as every English speaker once called it until the “diversity”craze took hold and persuaded the panjandra of the media that it was somehow offensive to people who speak other languages for us to use our own, and in particular certain well-established English names for places in certain countries — or for the countries themselves in the case of the ridiculous “Myanmar” (or Burma as it was known to the colonialist oppressor). This kind of thing has always been an especially silly bit of political correctness in the case of India, a country with twice as many English speakers as there are in the mother country and several local languages, all of which presumably have their own names for Bombay. But of course one is resigned by now to such media absurdities as politically “sensitive” reporters’ correcting foreigners for not being foreign enough. Actually, what must have made Mr Reeves uneasy was not so much that the aristocratic Indian was insufficiently Indian as that he was too aristocratic and (therefore) British. By talking posh and using the nomenclature of the former imperialist power he had marked himself with the stigma of being, as race-conscious American blacks have sometimes put it, “too white.”

It may be that Philip Reeves, like other white liberals, is eaten up with guilt about what some defunct economist has persuaded him is the shameful history of “imperialism” of his own people — and that, therefore, any reminder of such imperial history from one of its presumptive victims who is less indignant about it than he himself is must be painful. He may even feel the victim of ingratitude. Was it for this that he had repudiated his heritage as a member of the alleged oppressor race? But I think he was annoyed because the old-fashioned language was almost a social snub. The Indian had disdained to join him in membership of what, as a member of the media who invented it, he has doubtless grown accustomed to thinking of as that still more aristocratic élite whose supranational and utopian assumptions about the world — assumptions by which even the most theoretical or idiosyncratic sensitivities are catered for — are in their own minds the guarantee of their moral authority and political legitimacy. In short, liberal and multi-cultural tolerance are for him what “Christian civilization” was for the British empire.

I doubt that he reflects very much upon the irony, any more than the rest of the missionary media does. For them, such perfect, non-discriminatory equality, even if it is only linguistic, is primarily just a perpetual cause for self-congratulation about their own superiority to the ruck of mankind, still mired in the petty partisanships of the past — not only those of party but of traditional loyalties to class or nation, ethnic or religious identities — where these have not been formed by a common history of oppression. Their enlightened universalism is now our “official culture,” to use the terminology of the Russian literary theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin. That is to say, it has been formed by the ideology of those in power and therefore must always, to a greater or lesser extent, try to extinguish its “unofficial” rival — the more so, in this case, as the unofficial, particularly in the form of an unabashed and largely uncritical patriotism, was so recently official itself.

This fissure in contemporary culture was exposed with what even Barack Obama must by now regard as his injudicious decision to release the so-called “torture memos” of the Bush administration. For by doing so, he also opened up the question of the investigation and possible prosecution of his predecessors in office for putting the security of American citizens from attack by foreign terrorists ahead of the sort of enlightened humanitarian solicitude for the “human rights” of the would-be attackers which is now among the desiderata of the media and others of the official culture. It has not always been so, of course. Along with the media’s campaign of indignant moral outrage against the Bush officials there came a steady stream of revelations about how much Nancy Pelosi, in particular, knew and presumably approved of in the way of “torture” in the months following the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. In those days, the political pressure from the unenlightened patriots of middle America overwhelmed even the most devoted multi-culturalists — at least those who knew they would soon have to submit themselves to the electorate.

Even today, even amidst the apparently undiminished enthusiasm of the Obamaniacs and the equally undiminished unpopularity of the late Bush administration, criminalizing over-zealousness against America’s enemies is not likely to prove a politically popular course — as Mr Obama himself must have recognized when he attempted to deprecate any attempts by the more passionately anti-Bush element among his supporters to haul the factors and advisers of President Bush, if not the former president himself, into court. He may not be able to stop it now. The anti-“torture” fanatics are too oblivious of the consequences and too thoroughly persuaded of their own righteousness — partly because the assumption of such righteousness is integral to their identity as members of the official culture whose sense of its own legitimacy in power heavily depends on frequent bouts of self-congratulation about it such as that which ensued upon the release of the memos. And, as with Philip Reeves, the purpose of self-congratulation is partly also to stifle any sense of irony or illogic in the progressive program itself.

The illogic of the official culture’s attitude to “torture” was brought home to me as I listened to another radio broadcast, this one on Washington’s WTOP (commercial) news channel as an interviewer was questioning some foreign policy expert or another on the alleged American “double standard” in regard to nuclear weapons in Israel and Iran. This seemed to me like talking of America’s “double-standard” in its treatment of Britain and Germany during World War II. Israel is an ally of ours, and an ally of long-standing. Iran is a self-proclaimed enemy that we know has been responsible for the torture (the real kind), killing and imprisonment of American citizens. What on earth is a double standard for if not for its enthusiastic application in such a situation as that? Similarly, the liberal moralists often wrote or spoke with horror about the belief of the alleged “torturers” that “the end justifies the means.” What else would they expect to justify the means if not the ends? If there were not times when the morally alert have had to use ends to justify means, there could never have been any wars, even the “good” kind, and certainly no wars won — if that matters to you.

But the sort of crypto-pacifism which pretends it doesn’t matter is the only moral training that many secularly educated Americans receive anymore, and this is what’s really the source of the misunderstanding with which our culture is riven from top to bottom. Some significant portion of us, that is, live our lives according to pacifist and utopian assumptions while the rest of us are mired, like the poor Indian aristocrat who made Philip Reeves so cross, in an old-fashioned world of local and traditional loyalties, based on class or kinship, religion or ethnicity, history or geography. Above all, there is the local loyalty of patriotism, which presents all-but insoluble difficulties for our post-Obama politics because left and right now mean quite different and contradictory things by it. For those on the right, patriotism means what it has nearly always meant in human history, namely putting one’s country’s interests and security ahead of all other political considerations. For the left it means — and there are numerous precedents for this belief in the long history of American exceptionalism — making sure that one’s country is better, in the sense of less morally blameworthy, than other countries in its dealings with the world, at no matter the cost to its interests and security.

A brief illustration of the resultant misunderstandings was provided when the commander of the American Legion, David K. Rebhein, registered an urgent plea in The Wall Street Journal against the American Civil Liberty Union’s Freedom of Information request — one of many unforseen consequences of the President’s release of the “torture” memos — for the release and publication of photographs of the treatment of terrorist suspects in American custody. Mr Rebhein wrote:

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but is it worth the death of a single American soldier? Is any photograph worth the life of your Marine Corps daughter? Or your neighbor’s deployed husband? I would like to concede that these are tough questions, but they are really quite simple. The answer is a resounding “No.” Releasing photographs of alleged or actual detainee abuse in the War on Terrorism is not worth the life of a single American. Of course, as some have noted, the incidents at Abu Ghraib have already endangered our troops. So did any orders and policies that may have led to those incidents. But what is to be accomplished by continuing to provide ammunition and provocation to the enemy?

The answer, I’m afraid, is a resounding “yes,” at least to the ever-more progressive-minded ACLU, whose anti-patriotic motto for a generation or more past might as well be: fiat justitia, ruat caelum

It’s always easier, of course, for the partisans of justitia if they themselves manage to be somewhere else when the caelum starts falling, as is generally the case with the ACLU. Still, their devotion to their principles is such that they might well make the same argument even if they did have loved ones who were endangered by them. Certainly, Mr Rebhein and The Wall Street Journal are mistaken if they suppose that such an appeal to any loyalty save loyalty to principle would be even remotely likely to be heeded by the ACLU. That organization is in the business not only of universal human rights and freedoms, as it would claim, but also of repudiating in the name of those rights and freedoms any merely honorable or patriotic favoritism to one’s own kind. For instance, to Mr Rebhein’s daughter, husband or neighbor. And that repudiated loyalty ultimately includes patriotism itself (in the old sense), which to the logical progressive is tantamount to racism. That is not, I think, a common view even in the Age of Obama — at least not in the United States of America where patriotism once routinely took precedence over general principles in ways that almost everyone believed were entirely appropriate.

According to opinion polls, anything up to 65 per cent of Americans are still patriotic in this sense, apparently, since they want no investigations of the otherwise unpopular Bush administration “torturers.” But though they comprise a majority, theirs is now an unofficial view of the matter, and one with which the official culture is unlikely to have much to do, at least until it threatens to express itself in electoral form — which, as yet, it has not done. At least I assume it hasn’t, since my own liberal congressman, not hitherto distinguished for his high moral principles, has taken to the pages of The Washington Post to urge me and his other constituents to put such principles (as he imagines them to be) ahead of my own convenience and safety and to welcome to our home town the terrorists scandalously but safely incarcerated by the benighted Bush régime at Guantánamo Bay.

There, Rep. Jim Moran (D-Va.), having established in his own mind that the Guantánamo prison is a “stain on the national character,” attempted to demonstrate the point by noting that

President Obama and Sen. John McCain both pledged last year to close the Guantánamo facility because they recognized that the United States is governed by the rule of law and defined by our embrace of universal human rights. Indefinitely detaining individuals without charge violates the most basic principle of habeas corpus, greatly damages our international reputation, and fuels both terrorist recruitment and anti-American sentiment.

He then proceeded to volunteer our town, which lies across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., for the terrorist “trials.” He admits that having them there would be a serious inconvenience and possibly a danger to us, but he is confident that, like him, we all must care more about “universal human rights” than we do about our own safety. Probably, too, there are among my neighbors some who don’t mind dying, so long as Mr Moran feels good about himself. The survivors among us can at least congratulate ourselves, as he does, before the bar of world opinion for the ludicrous show-trials — for that is what they will most certainly be, whatever their results, in the absence of the sort of evidence that the very concept of our legal system depends on — of the human scum who have devoted their lives to killing us merely for being Americans. “Often,” he writes with almost unbelievable smugness,

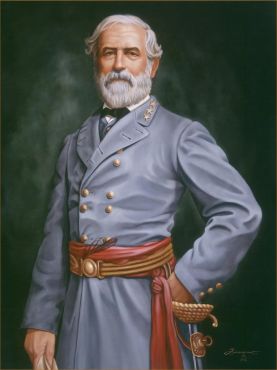

doing the right thing is neither popular nor convenient. By and large, Alexandrians are civic-minded people and are ready to do their duty if it serves the greater good. They have shown this public spirit time and again [by demonstrating] the kind of courage and patriotism that can be traced to the city’s roots as the home town of George Washington and Robert E. Lee. Taking the easy route and joining the chorus of those crying “not in my back yard” is appealing. But that’s not the Alexandria I know and have represented in Congress for nearly 20 years. Even before that, I served as mayor of the city, and I am confident that if asked to step forward, Alexandria would demonstrate resolve for a higher purpose, echoing John F. Kennedy’s call to accept the challenge presented because it is what happens to be right and good for our nation. Trying the accused, no matter how heinous the accusation, in a fair and transparent judicial procedure will reestablish our international moral authority and thus strengthen our national security.

What utter, sanctimonious piffle! It was enough to make me even not-so-sorry that he got in trouble with the politically correct crowd, as anyone less self-absorbed could easily have foreseen he would, by seeming to have a good word to say for that notorious champion of slave-owners, our fellow Alexandrian Robert E. Lee.

Congressman Moran’s idea of “international moral authority” — even as something that, in defiance of all evidence to the contrary, is supposed to “strengthen our national security” — is an undeniably popular one in the official culture, and one that it never ceases to try to sell to the rest of us. As I pointed out in these pages three months ago (see “The Death of Politics” in The New Criterion of March, 2009), President Obama himself attempted a similar sales job in his inaugural address when he advanced the highly dubious proposition that “the choice between our safety and our ideals” traded upon by his predecessor was a “false” one. Like some of his allies in the media, the President wished to proclaim, in effect, that the moral problem of ends and means simply didn’t exist. The ends couldn’t justify the means — not because he was too high-principled to allow them to do so but because, as a simple matter of practice, what he was pleased to call torture didn’t “work.”

Even when it did work, as his own Director of National Intelligence admitted it sometimes did (in a memo later suppressed), our progressive President stuck to his guns. “I am absolutely convinced it was the right thing to do,” he said of his decision to stop the enhanced interrogation procedures, “not because there might not have been information that was yielded by these various detainees that were subjected to this treatment, but because we could have gotten this information in other ways.” There’s a faith-based proposition if I have ever heard one, and it conveniently exempted him from having to make any of those “hard choices” he would be so bold to confront if he ever recognized any that were not merely rhetorical. Don’t worry, fellow progressives! The good guys and the bad guys in your morally simplistic world are where they have always been, and the celebrity- superhero president has confirmed his “international moral authority” by dissociating himself from the deeds of his predecessor. We’ll just have to hope that the official and media culture’s moral authority will keep us as safe as mere patriotism did.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.