Rotten Apples

From The American SpectatorIn an article in a recent edition of the London Daily Telegraph titled “More Sex Please, We’re Grownups,” Josa Young, a novelist, writes that “in order to create fully rounded human beings, and describe their relationships with each other” it was necessary for her “to tackle the subject of sex” — by which, the context suggests, she means the act of coition. The implied syllogism goes like this. Writers of fiction have to write about relationships. Sex is a key component of relationships. Therefore, writers of fiction have to write about sex. But if that is indeed her reasoning — she doesn’t make it quite clear — it masks an equivocation on the word “sex.”

Sex as one of the essential attributes of our humanity — or even our animality — is indeed almost impossible to leave out of fiction, let alone fiction written about “relationships.” Male and female He created them,” says the Bible, and the taxonomy, at least, would be hard even for Richard Dawkins to disagree with. But “sex” in this sense is not the same thing as what Ms Young calls the “raunchy scenes” that she thinks equally essential to her fiction. I have not read her novel, titled One Apple Tasted, so I cannot judge of her own “raunchy scenes.” But as a general argument, the contention that raunchy scenes are essential to a realistic account of relationships doesn’t persuade at all. Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra is all about sex, but it contains (as written) no raunchy scenes at all.

In fact, I would go so far as to say that the realism quotient of a work of fiction is almost invariably in inverse proportion to the number and raunchiness of its raunchy scenes. This is if anything even more true when it comes to violence. Violence is also an equivocal word. On the one hand, it still retains some of its original pejorative sense and so is self-discrediting. All violence is bad. On the other hand, it is so much a part of our experience of the popular culture, especially movies and comic books, that we would feel the lack of it as a deprivation almost on a par with that of sex. “Violence is the funnest thing you can do at the movies,” says Quentin Tarantino. “It’s the funnest thing to watch. I’ve always felt action directors come as close as you can get to pure cinema. Literature can’t do it the same way. Painting. TV. None of the other art forms can do it the same way.” That’s throwing down the gauntlet on behalf of your medium!

But it is just because you can show on film what you can’t in any other medium that its representations so easily belie reality. After all, real violence isn’t fun at all — or not unless you’re mentally disturbed. It only becomes fun by frankly detaching itself from reality and so giving up what art has traditionally been understood to offer us, which is a representation of reality. As a result, even movies which attempt to represent violent acts in a spirit of moral seriousness rather than fun, movies such as Cyrus Nowrasteh’s The Stoning of Soraya M., are dragged, willy-nilly, into Tarantino territory. Mr Nowrasteh has the laudable purpose of opposing the treatment of women under Islamic fundamentalist regimes, but by privileging the visual over the moral truth of the atrocity at the film’s center, he turns it into yet another cinematic cartoon, competing on their own terms with Reservoir Dogs or The Passion of the Christ. Why did you say they’re throwing stones at that chick? The event’s meaning is lost in the sensation of its appearance.

Well, that’s been going on for a long time now. As I did in the summers of 2007 (see “The Hero Vanishes” in The American Spectator of September, 2007) and 2008 (see “Trash Triumphant” in The American Spectator of September, 2008), this summer I presented a series of eight films in eight weeks at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, this time on the subject of “Crime and Punishment.” As in the past two years, my aim was to show how the movies, like so many other things, changed during the 1960s. What came before that doleful decade was a popular, often vulgar but also artistically accomplished medium of entertainment; what came after it was mostly cartoonish if occasionally artistically pretentious trash. Proper movie heroes like Gary Cooper and John Wayne gave way to comic book figures in silly costumes, like Christopher Reeve’s Superman or only lightly disguised supermen such as Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones. Romance may have been artificially heightened in movies like The Philadelphia Story or An Affair to Remember, but such movies still treated romance seriously — something that the post-1960s sex comedies like Annie Hall or When Harry Met Sally could no longer do. Romance had become, at best, a sentimental add-on to the serious business of “relationships.”

|

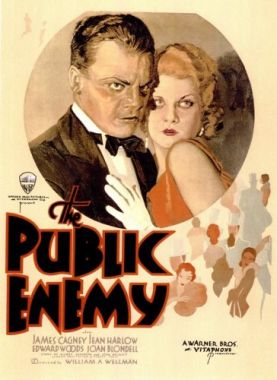

The same kind of transformation was visible in the eight movies about crime and punishment, which started with The Public Enemy of 1931, the movie that made James Cagney a star, and then moved on to Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), George Stevens’s A Place in the Sun (1951), Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958), Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat (1981) and the Coen brothers’ Fargo (1996). The most instructive comparison I found was between The Public Enemy and Bonnie and Clyde, since both deal with poor kids who become “somebody” by undertaking a criminal career. In both cases, too, we are expected by the film-makers to sympathize with the criminal heroes, although in the former case this was more on account of Cagney’s screen charisma than any conscious intention of the director, William A. Wellman.

The difference between the two movies lay in their portrayal of the criminals in relation to their social milieu. The Public Enemy, made during the Depression, puts Cagney’s tough-guy act in the context of the basic decency of those around him, especially his mother and brother. Bonnie and Clyde, made 30 years later and with a more or less explicit political purpose, turns the social milieu into a Marxist caricature: barely human bankers and cops on one side and their downtrodden victims on the other. The victims all admire Bonnie and Clyde for the blows they strike against their common oppressors. As we saw in this summer’s homage to Bonnie and Clyde, Michael Mann’s Public Enemies, the idea that ordinary folk in the 1930s looked up to heroically revolutionary gangsters and crooks has become a Hollywood commonplace, reinforced by popular historians such as Brian Burroughs, on whose book Public Enemies is loosely based. He claims that, during the Depression, “legions of disaffected Americans cheered on an army of outlaws who rampaged through the Midwest, robbing banks and kidnapping millionaires.”

I don’t believe it. What scraps of evidence Burroughs has to support his case do not come anywhere near justifying “legions of disaffected Americans.” Like Bonnie and Clyde and Public Enemies, his is a retrospective view, strongly colored by left-wing politics and its understanding of crime. In The Public Enemy of 1931, the title is not (as it is in Public Enemies) ironical. Cagney really is seen as an enemy of the public. For all his cocky bravado and charm, he himself has internalized the community standard and so is at some level ashamed of what he does. He doesn’t want his mother and brother to know. In Bonnie and Clyde, the golden couple proudly announce: “We rob banks,” while Bonnie’s family keep a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about their exploits. Clyde’s only shame has to do with his impotence, which was an invention of the film-makers, and his overcoming that in the movie’s penultimate scene thus becomes a synecdoche for the shamelessness that Mr Penn and the rest were elevating to a high principle.

I think it is this lack of shame which made the movie seem so revolutionary and authentic in its own time — and which makes it look so dated and inauthentic in retrospect. Nostalgia-junkies may look back with affection on that period of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s when the throwing off of sexual and other kinds of inhibitions seemed like a benevolent and revolutionary act — something that, if repeated often enough, had the power to save the world from war and poverty. Today, there can’t be many people, even on the cultural left, who would want to return to those days. But in a way we are still in them, since the unreality which then settled in and subsequently became the norm for the movies and for other sorts of artistic expression has a gravity of its own which we are unable to escape. Trapped in the postmodern fun-house which is the legacy of Bonnie and Clyde and other movies of the period, we have to find some way back to reality.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.