Damned United, The

Not long ago, a player for the British rugby team, Harlequins, “one of the game’s most venerable clubs,” according to the London Daily Telegraph, was caught attempting to cheat by biting on a blood capsule in order to feign injury so that a specialist substitute could be brought into the game. Afterwards, a number of club officials tried to cover the incident up. It was a scandal of the kind which periodically roils the national media in Britain in relation to one of the two iconic national games — the other is of course cricket — associated with the imperial and upper-class ethos of yesteryear. English football, oddly known to us as “soccer,” an upper-class British slang term of the 1920s, is a different matter. As the saying (among rugby players) goes, rugby is a ruffians’ game played by gentlemen and soccer is a gentleman’s game played by ruffians.

That class difference still persists. According to a new book published in England by Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski, “of all the 34 England team members who have played at the last three international tournaments, only five came from anything approaching a middle-class background.” That may be why, although occasionally there are why-oh-why articles in the British press about falling standards even among these boorish “footballers,” for the most part soccer-players are not expected to observe gentlemanly standards of behavior, on or off the pitch. On the contrary, their antics are a rich source of material for the popular culture and especially televison, where one of the most popular series in recent years was a lurid soap opera called “Footballers’ Wives.”

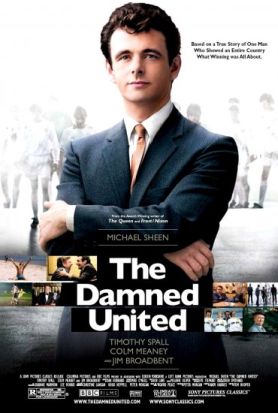

But neither are British ideas of fair play entirely bound up with class distinctions. Tom Hooper’s The Damned United, adapted by Peter Morgan from David Peace’s novelized history, tells the story of one man who tried to impose an alien sense of honor on Leeds United, the powerhouse of 1970s British football, with spectacularly disastrous results. The movie loves Brian Clough (Michael Sheen), bumptious, inept and foul-mouthed as he is and was (he died in 2004), and it makes us love him too — if only for the innocence and bravery of his quixotic quest. Amazingly, it brings this off in spite of representing the feud between him and Don Revie (Colm Meaney), United’s previous manager, as a matter of petty spite. When Clough was manager of up-and-coming Derby County, they had drawn United in a Cup tie — when any two teams in the league may meet — and had rolled out the welcome mat for the great Don Revie, only to be snubbed by him. Later, after Derby County had won the league title and he had been chosen to replace Revie on the latter’s elevation to manager of the national team, Clough had begun his tenure there by renouncing him and all his works.

This might not have been so bad if he had been even moderately discreet about it, but discretion was not Brian Clough’s style. He proclaimed not only to the Leeds players but to the world at large that their storied record of success under Revie had all been obtained fraudulently. “You lot may all be internationals and have won all the domestic honors there are to win under Don Revie. But as far as I’m concerned, the first thing you can do for me is to chuck all your medals and all your caps and all your pots and all your pans into the biggest f***ing dustbin you can find, because you’ve never won any of them fairly. You’ve done it all by bloody cheating.” The sheer chutzpah of it takes your breath away. Could the man have been so great a fool? It seems an illustration of Kuper and Szymanski’s saying that “Anyone who spends any time inside football soon discovers that just as oil is part of the oil business, stupidity is part of the football business.” And yet there is a kind of magnificence about Clough’s folly that would itself have made it worth making this movie in order to celebrate.

Intended or not, it was a self-immolatory gesture — his career at Leeds lasted a mere 44 days — and the movie could hardly have been of feature length without its complementary sub-plot concerning Clough’s relationship with his friend and second-in-command, Peter Taylor (Timothy Spall), who had much to do with his brilliant successes at Derby County and, later, Nottingham Forrest, but who broke with him over his acceptance of the Leeds job when he — and Taylor — were still in the first year of their contracts to manage Brighton and Hove Albion. Clough was too proud a man ever to admit to any mistakes vis- -vis Don Revie — who claimed never to have intended any snub to Clough at Derby County — or the Leeds players, who naturally hated him. But his subsequent humility before his oldest friend, which is shown here in an affecting climactic scene, is a big part of what is meant to win our hearts for dear old Cloughy and for this affectionate movie about him. It won mine, anyway.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.