Look At Me

From The American SpectatorIn our time, freedom of speech is almost a non-issue. True, we encounter some problems with multi-cultural sensitivities and especially Islamic ones. The craven decision by Yale University Press not to reprint the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammed in a book ostensibly about the cartoons amounts to a bizarre if rather terrifying reminder of the moral terra incognita which lies just beyond the enchanted land of libertarian whimsy we have inhabited for most of the last half century. The barbarian hordes with their unforgiving honor cultures and violent sensitivity to slights against their amour propre are as yet making only occasional and limited incursions among us to demand their tribute from our once-treasured freedoms. For the most part, our fantasies of limitless free self-expression remain undisturbed by the only shadow which might realistically fall upon them. Some day.

Our concerns lie instead with that more recently discovered but, if anything, even more highly valued freedom, the freedom to be attended to by the world at large. You will of course tell me that there is no such freedom in reality, and you will be right. I have said so myself in this space (see “The Shock is Over” in The American Spectator of May, 2008) in the course of noticing how Saskia Olde Wolbers, one of the army of mostly unattended-to artists in our heavily over-populated “creative” world has referred mournfully to “the meaninglessness of being unobserved.” Since then, our national crisis of inattention has only grown more acute. Now it’s not just those ever-growing numbers of obscure artists, poets, actors and other such riffraff that the wider world is neglecting but the once enormously popular news media with their delightful fables and fantasies of American public life. Having grown rich on the spare pennies of eager “news” consumers for the past century and more, these media are now being abandoned by their audiences in such numbers and with such suddenness that Dan Rather, for one, thinks them in need of one of Mr Obama’s celebrated bail-outs of old and now-bankrupt industries and technologies.

Dan is of course a fantasist, but then so is the President, as I have pointed out already (see “The Triumph of Fantasy” in The American Spectator of July/August, 2009). Why should we expect anything else when our whole culture, as the summer “blockbuster” movie season has so recently reminded us, is based on fantasy? If you were going to write the political history of fantasy, one good place to start would be with Adolf Hitler’s conceit of himself as an artistic genius, which the German art historian Birgit Schwarz thinks was crucial to his later fantasies of world domination. “Genius” to him, she says, meant “a larger-than-life talent who was permitted to do anything, including evil things. The genius has outstanding ideas, and they must be implemented, even if they are completely amoral.”

Of course it would be tendentious and completely unfair of me to describe the millions of unrecognized, unappreciated artists whom the rest of us can’t be bothered to read, or watch or listen to, even when their works are readily available on the Internet, as little Hitlers in the making. Few of them, I imagine, harbor fantasies of either genocide or world domination, let alone the wherewithal to make such fantasies come true. But the problem with fantasy is also the point of it: that there are no natural limits. You can fantasize anything you want, just as, if you are a left-leaning Supreme Court justice with a hankering for some such progressive bibelot as abortion on demand, you can find it implied in the United States Constitution. Or if you are a left-leaning president, you can fantasize that it is possible to “reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals” and, therefore, hale the more zealous among those charged with protecting us from terrorist attack into criminal court, as a certain President has recently promised to do.

In Quentin Tarantino’s artsy version of the summer blockbuster, Inglorious Bastards (I decline to join him in misspelling the words), the auteur fantasizes about the death of Hitler himself in a French cinema. The Fuhrer is incinerated along with the rest of his Nazi henchmen and the German high command by one of his Jewish victims and her African lover who have prepared his funeral pyre from a library of highly inflammable nitrate film — a highly Tarantinian demise. As far as I know, I’m the only critic to have protested either that Hitler didn’t, in fact, die in that fashion or that it was inconceivable — though obviously not unfanciable — that he could have done so. Oh please. Just imagine where Quentin Tarantino would be today if he had been expected by audiences to make movies that looked even as much like real life as the B-movies of the1940s and ‘50s that he so often parodies. He’d be back in that legendary video store where (so the tale goes) he learned all that he knows about movie-making from the least life-like of old movies, comic books and “pulp fiction.”

To most of us, there is something desperately uninteresting about other people’s fantasies, just as there is about an account of his last night’s dreams by the breakfast-table bore. QT’s breakthrough as an artist was to find a way to make his fantasies interesting to others by means of what much more sophisticated critics than I call “intertextuality.” Academic experts in the popular culture and movie antiquarians — as more and more of us may aspire to be in the age of Netflix and YouTube — can apparently find endless delight in spotting Mr Tarantino’s allusions to other movies or cultural memes in his “dense textured” movies. So much so, indeed, that they hardly have time to notice what crap they are as movies themselves. Still, you can’t take away from his achievement the fact that these movies, no matter how crappy, have found a way over the wall of public indifference, and that they take him with them into the land of fame and fortune.

|

All art needs heroes. In modernist art, the artist was the hero on account of his art. Now he’s a hero if he can just figure out how to get his art noticed. That’s the whole point of conceptual art, which has little or no content qua art (in the old sense of something beautifully wrought) apart from the concept that promises to get it talked about. It’s hard to tell whether this assimilation of art to publicity has percolated down from the high to the popular culture or risen up, like sap, from the popular to the high. But there’s hardly any difference between the two now anyway. That’s part of the message of the wildly popular but also ostentatiously highbrow AMC television series, “Mad Men,” which fascinates at least in part because it both shows us and tells us that art is publicity and publicity is art. Jon Hamm’s Don Draper has the kind of genius that even Hitler, had he escaped from both the Berlin bunker and Quentin Tarantino’s French cinema and were alive today, might aspire to. And he has a lot more sex than Hitler ever had.

The talent for getting — and staying — noticed is the only art that counts. So Tom Shales inaugurates a new column in The Washington Post “about our culture” and proceeds to unreel a 1500-word thumb-sucker on the prospects for success of a Mr Conan O’Brien, who is apparently some kind of televisual comedian currently suffering from what he, Mr Shales, fervently hopes will be only temporarily low ratings. We don’t even need to know who this “Conan” is to root for him to stay in the public eye. Likewise, the audience of the popular summer film, Julie & Julia by Norah Ephron, were all rooting for spunky Julie Powell to break through to world-wide fame with the help of the then-new medium of blogging and the shameless gimmick of preparing all 524 recipes in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking in a year. The story, which also features Meryl Streep as the late Mrs Child, of course has a happy ending. The real-life Julie got a book deal and now a movie out of her stunt, so any conceivable criticism is disarmed.

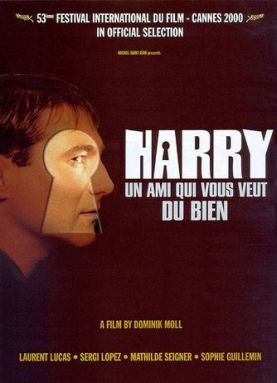

Hooray for Julie! Who could wish her less successful, less rich, less famous or played in the movie by anyone less adorable than Amy Adams? But I’d prefer to rent the video of With a Friend Like Harry. . ., a French film of 2000 by the German-born Dominik Moll, about a poet whose comatose genius is shocked back into life by the discovery that his long-disregarded juvenile oeuvre has found an audience solely on its dubious merits and not on account of his mastery of publicity or compelling personal story. True, it is an audience of one, and that one a criminal madman, but for any real artist that ought to be enough.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.