An American Tragedy

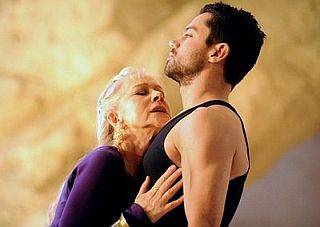

From The American SpectatorJust as we have now arrived at the cultural moment where we have to define art as whatever is displayed in an art gallery or museum, so we also have to define comedy as whatever is said on a late night comedy show. But my surprise at hearing the audience of “The Late Show with David Letterman” laugh and applaud its way through Mr Letterman’s account of a $2 million blackmail plot against him — a plot based on what he hilariously described as such “creepy things” about him as his simultaneously confessed proclivity for sleeping with his female employees — was not so great as it would have been a couple of weeks before. That’s when I had gone to see the British National Theatre’s production of Jean Racine’s Phèdre in Washington, lured by the promise of the glorious Helen Mirren in the title role. The theme of this tragedy was also, it was said, torn from the tabloid headlines. A woman — Phèdre — falls in love with her stepson and, when she is spurned, accuses him of rape. It ends, as tragedy usually ends, in murder and suicide. Yet there, too, the audience laughed and laughed and laughed.

I’m not ashamed — well, only a little ashamed — to confess that I have been a fan of Miss Mirren’s since her fantastically sexy romp in the surf with James Mason in Michael Powell’s otherwise lamentable Age of Consent (1969), when at the age of 23 or so she could still pass for jail bait, and I thought she was the making of Stephen Frears’s The Queen three years ago. Nor did she disappoint with her performance in Phèdre, which was terrific. Moreover, it had the effect of raising the level of the whole production, directed by Nicholas Hytner. There were especially fine performances by Dominic Cooper as the stepson, Hippolytus, Stanley Townsend as her husband and his father, Theseus, Ruth Negga as Aricia, whom Hippolytus loves, and the great Margaret Tyzack as Oenone, Phèdre’s maidservant, who encourages her mistress’s illicit passion. The 17th -century French original had been very creditably rendered into English by the late poet laureate of Britain, Ted Hughes.

Not the least of the production’s accomplishments was to make Racine enthralling. Generally one finds that, in translation anyway, a little of Racine goes a long way, and in English, even that of Mr Hughes, you don’t get the poetry. Also, poetry or no, the play adheres strictly to the French neoclassical maxim that tragedies should be tragic and comedies comic, and that Shakespeare must forever suffer from the critical taint of having mixed the two up so promiscuously. Tragedy has to be as well-done as it was on this occasion not to become overbearing when there is no comic relief. And yet the audience laughed. Either they thought that Racine or Hughes, or Miss Mirren or Mr. Hytner, had failed in their attempts to avoid bathos — which seems improbable, given the standing ovation they gave it at the end — or they thought they were supposed to laugh. Like the “Late Show” audience, they had come to laugh and they were determined to do so.

The production took place under the auspices of the Shakespeare Theatre Company of Washington, and audiences there know they’re supposed to laugh at Shakespeare, as they always do — so lustily, indeed, that it sometimes seems to me to be rather in excess of the comedy of the scene in front of them. As I noticed in this space a few months ago (see “The Triumph of Fantasy,” July/August, 2009), the STC audience also laughed their heads off at a production of Noel Coward’s Design for Living that I found desperately unfunny. Perhaps it is my own sense of humor that is at fault? But I made a note of a few of what the audience found to be the laugh lines in Phédre, so you can make your own mind up about that:

- “Prudence and restraint are out of date.”

- Phèdre’s question to Oenone about her attempted suicide: “Why did you prevent me?”

- Phèdre to Oenone about the latter’s caution regarding her wish to believe in Hippolytus’s returning her love: “Serve my madness, now, not my reason.”

- Phèdre’s apostrophe to Venus: “See how far I have fallen!”

- Phèdre’s devastation at learning of the love of Hippolytus for Aricia — expressed, by the way, with words that sounded torn from her heart: “I have a rival!” and then again when she said: “My hands are itching to squeeze the life out of that woman.”

- Aricia to the monster-slayer Theseus, hinting of Phèdre’s guilty secret: “Not every monster has been accounted for.”

Funny? I don’t think so. One is driven to the conclusion that some significant proportion of the audience, at least, didn’t know what they were watching — apart from Helen Mirren, a celebrity, getting herself into rather an emotional state. Since the play was, like most 17th century French tragedy, all about honor, and as I have written a book to explain why our contemporaries in America and other Western countries have very little idea of what honor is anymore, I suppose I should not have been surprised. It didn’t help, either, that a program note headed “A Myth of Desire” solemnly informed us in a subhead that “the ancient myth of Hippolytus and Phaedra is a myth of desire. It asks us to reflect not only on the terrible consequences of incestuous passion, dysfunctional love, and perverted celibacy — but also on their conflicting explanations. How do we explain the destructive power of passion? Who is to blame when love goes wrong?”

Clearly, Racine was out of his depth in this play. Those are questions that only Oprah or Dr. Phil could answer. The “perverted celibacy” part, by the way, was presumably because in one version of the myth, Hippolytus had sworn off women, though Racine shows him as being in love with Aricia. But the popular culture today, like the British underclass, accepts what Dr. Anthony Daniels calls “the hydraulic model of human desire, according to which passion is like the pus in an abscess, which, if not drained, causes blood poisoning, delirium, and death.” In other words, all celibacy is a form of perversion because it is unhealthy and an offense against the hygienic properties of coition. What better presumptive answer, then, to the question of “who is to blame when love goes wrong?”

As it happened, on the same day that I went to see Phèdre, my local paper, The Washington Post, ran not one but two articles occasioned by the premiere of new show on ABC television called “Cougar Town” which, as the review by Hank Steuver opined, “may be the most deliciously profane network show ever made.” I think he meant “obscene” rather than “profane,” since his example of its alleged profanity was a scene “in which a teenager discovers his mom performing oral sex by the pool.” It would have been profane (that is, offensive or opposed to religion or the gods) as well as obscene in Phèdre’s day, which was one reason she was in such a state but, well, as Miss Mirren’s audience and Mr Steuver remind us, times change.

The accompanying article, by Monica Hesse and Ellen McCarthy, had no fault to find with either profanity or obscenity and heartily approved of older women’s couplings, sanctified or otherwise, with younger men, but it did express a primly feminist disapproval of the word “cougar.”

It’s not just that using a predatory animal to describe older women makes it sound like the men involved are vulnerable prey. Like sharp teeth and claws are scaring them into bed — rather than, you know, their own desires. . . It’s not even the double standard, though that’s part of it: There’s a corresponding name for single males who prefer to date younger females. They’re called “men.” The biggest problem with the cougar craze is that it takes an age-old dating dynamic and pretends it’s something new. Sixteenth-century Frenchman Henry II was just 15 when he began a long-term affair with a 35-year-old woman. It’s been more than 40 years ago since Mrs. Robinson dropped her robe in front of young Benjamin Braddock. And Susan Sarandon, 62, and Tim Robbins, 50, have been together for two decades now.

It “takes an age-old dating dynamic and pretends it’s something new”? But it is new. Not the older-woman younger-man bit but the dating bit. Up until quite recent times there was no such thing, and for most of the time there has been “dating,” it would have been thought indecent by most people for it to occur in the cougarish pattern — which is why Mrs Robinson in The Graduate had the impact she had at the time. People were shocked at the idea of “cougars.” Now they’re not. Now cougars are funny, which is why they’re making sitcoms about them.

Presumably, it also has something to do with the reason why the audience laughed at Helen Mirren’s Phèdre. The Post writers are the ones who are pretending, by pleading with people to treat cougarism as normal and the spectacle of mature women turned sexual predators as neither shocking nor admirable but just the natural way of things. Trouble is, historically speaking, it’s not the natural way of things. Even today, when cougars are no longer cried about, they’re still unusual enough to be laughed at. Tragedy has been converted by history into comedy. Can it be that there are still those who are unhappy with the exchange?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.