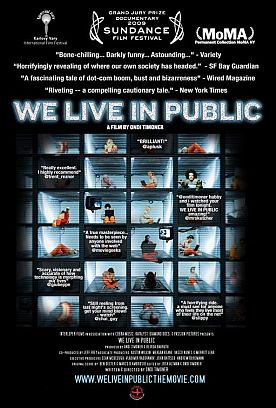

We Live in Public

We Live in Public is a documentary about Josh Harris, an entrepreneur from the first dot.com era who made $80 million as a founder of Prodigy and other on-line businesses and then, rather like that other iconic figure of the 1990s, Newt Gingrich, decided that he fancied himself as an artist and an intellectual and a prophet rather than sticking to what he was really good at. Readers may have their own views about the success or otherwise of Newt Gingrich’s intellectual ventures, but there can hardly be two opinions about Mr Harris’s. He crashed and burned spectacularly, which is the reason why Ondi Timoner thought his life story would make for a compelling cinematic experience. Just for the record, it doesn’t.

Mr Harris’s ideas for becoming an “artist” were more radical than those of Mr Gingrich, who had confined himself to writing novels and making movie documentaries of his own. For Josh Harris’s materials were living human beings. Having created in 1999 a sort of libertarian commune, if that’s not a contradiction in terms, called “Quiet” in which he persuaded 100 people to part with their privacy in exchange for being given a place to live in Manhattan and food to eat and (apparently) unlimited freedom, he later became, along with a girlfriend, his own exhibitionistic guinea pig in this line, putting his life on camera, before going broke, like so many others, in the dot.com bust of 2000-2001.

On any reckoning, his “experiments” in living in public would have to be judged a failure, and Josh’s subsequent history — as an apple farmer, a would-be entrepreneur (again) and visionary and, now, some kind of Mr Kurtz figure in Ethiopia — could hardly be anything more than deeply depressing material, particularly as he appears to have learned nothing from his failures. But Josh had one thing going for him, which was that, seen in the right light he could be represented as a prophet of social networking on the internet and, in particular, its connection to the celebrity culture. As he says of the experimental subjects of “Quiet,” Andy Warhol got it wrong: people didn’t want 15 minutes of fame. They wanted 15 minutes every day.

Of course, even Josh recognized that you sort of have to be famous for something, even if it is something trivial or pathetic. So he created an alter ego for himself, a clown called Luvvy after Mrs Thurston Howell III on “Gilligan’s Island” — the iconic TV show which he pretended to regard, along with the medium of its original transmission, in loco parentis. The public psychodrama of a man claiming to have been raised by TV because his father was mostly absent and his mother mostly drunk, had an obvious public appeal to it in spite of, or perhaps because of, the fact that Luvvy was creepy in the extreme. As, of course, was the televised ménage of Josh and Tanya which came along later.

But there is a limit to that kind of thing, as I predict you will be thinking, too, if and when you exit this unpleasant and unhappy movie. If a tragedy had resulted from Josh’s artistic experiments with people, as it easily might have done, he would perhaps have had a better shot at being a celebrity himself. As the experimentation always just sort of peters out, however, I don’t see him winning back the followers who gave him his fifteen minutes of fame, or replicating them on the basis of what Ondi Timoner shows us here.

The film begins with a videotape that Josh made to send to his dying mother in 2005 — instead of responding to her dying request to visit her. “Good luck,” he ends it. “See you on the other side when I get there. Say hello to my ancestors and relatives; give them my best and — good bye.” That Ms Timoner appears to imagine this will pique our interest in her psychologically stunted hero, rather than just disgusting us, should tell you all you need to know, both about him and about the impulse which has produced this movie.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.