Brace Yourself

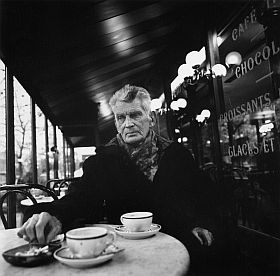

From The American SpectatorSamuel Beckett

“Beckett’s despair is as bracing as ever.” So, at least, says the Sunday Times critic proudly quoted on the marquee of the new production in London by Simon McBurney of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, which was first performed there in 1957. Mr McBurney himself plays the hapless dogsbody Clov to Mark Rylance’s imperious but blind and immobile Hamm. Miriam Margolyes is Nell and Tom Hickey is Nagg, the folks in the garbage cans. The effect of their efforts, if not exactly “bracing,” is a powerful one, but the play is so minimalist that it is almost actor proof. Yet I can’t get that word “bracing” out of my head. What in the world is bracing about despair? It’s a paradox, of course, but there is shame in such a paradox, an admission that we are indulging ourselves in a pleasure, or more than one pleasure, that once was, like pornography, forbidden — namely, the narcissistic pleasure of self-pity.

And, as with pornography, at some level we still know that there was a reason why such things were once forbidden, which is why the shame attaching to them lingers on long after you might have expected the world at large to have adopted as indulgent an attitude towards the pleasures of the imagination as it has to other sorts of pleasures. It’s not just the British who find despair bracing, but they seem to lead the world in this approach to it. A survey recently published in Britain found that the nation’s favorite poet is the American-born T.S. Eliot. Something tells me that Eliot would not have received such an accolade if he were better known for the Four Quartets and his later, religious work than he is for “The Wasteland” — which is another example, I suppose, of bracing despair.

It used to be that people read — or listened to or recited or memorized — poetry for its “sustaining” or consoling qualities. Even the barely educated of my parents’ or grandparents’ generation were likely to have by heart a poem like Arthur Hugh Clough’s “Say not the struggle nought availeth” or William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus.” That, by the way, is the one that begins: “Out of the night that covers me,/Black as the pit from pole to pole,/I thank whatever gods may be/For my unconquerable soul.” Now, it’s the name of Clint Eastwood’s new film about Nelson Mandela. The struggle for racial equality is the one non-despairing thing we’re still allowed to feel inspired about, I guess. Otherwise, it’s “April is the cruellest month” — if it’s anything.

At one point in Endgame, Hamm affects to pray, announcing of the silent God he addresses: “The bastard! He doesn’t exist!” In 1957, the censor — Britain still had such an office then — wouldn’t allow the play to proceed with that line in it. Beckett had to change “bastard” to “swine.” It was OK to assert God’s non-existence but not (yet) to call Him a bastard for not existing. Naturally, Mr McBurney’s production restores the original language, whose paradoxical insult to One who is also supposed to be a cipher is presumably another example of bracing despair — since it or something like it has been often repeated subsequently, and with the same childish pleasure in naughtiness that Hamm, if not Beckett, must have felt. It is, as I have written elsewhere, what informs the spirit of the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man which, like Endgame, treats God’s non-existence as comedy, though the Coens, unlike Beckett, don’t have the nerve to write proper tragi-comedy. The god of their Oscar-winning No Country for Old Men was also a bastard, but he came a little uncomfortably close to not not existing.

Still, the brothers’ quirky theology and good jokes are preferable to the lugubriousness of those who lack a sense of irony and whose atheism is an excuse to wallow in self-pity and — its invariable concomitant — self-importance. In the new British film about Charles Darwin, Jon Amiel’s Creation, T.H. Huxley (Toby Jones) is made to say to Paul Bettany’s Darwin: “You have killed God, Sir. And good riddance to the vindictive bugger.” Huxley may have been an atheist, but I doubt that he would have indulged in such a vulgarism as that. This is the brash, unlettered and distinctively present-day voice of John Collee’s crudely moralistic screenplay which also has Huxley informing Darwin of a committee “comprised of” himself and others. So much for “The melancholy, long withdrawing roar” of the “sea of faith” as heard by Matthew Arnold. Now it’s the Bronx cheer of Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens, the vogue for whose triumphalist atheism I take to be what lay behind the making of Creation.

A screen card at the beginning of the movie informs the viewer that “Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species has been described as the biggest idea in the history of thought. This is the story of how it came to be written” — but of course it is nothing of the kind. It may be the story of how all those fashionable atheists came by their lack of religious convictions, but that is not the same thing at all. Charles Darwin, it’s true, lost a young daughter named Annie (Martha West) — who here gets into the spirit of things by telling her father that she likes a sad story because “it makes me cry” — but to draw a straight line from his grief at her death to his loss of faith in God to his publication of The Origin of Species as a vindication of Huxley’s militant atheism is a cartoonish over-simplification, the product, I think, of the current dramatic convention that grief is sacrosanct.

|

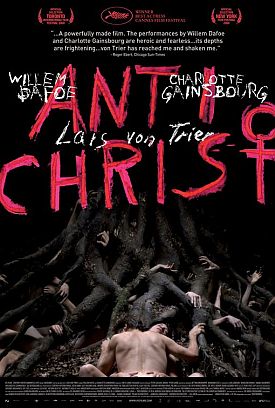

In Beckett grief, like despair, was comic, but the therapeutic culture has since taught us that the authenticity of raw emotion acts as an apology for any bad idea, or bad art, it may be supposed to produce. It goes without saying that we must believe in Darwin’s unbelief because of the genuineness of the emotion which, so we must also believe, produced it. Nonsense! Yet some such idea is built into the culture itself today. It must also have been behind Lars von Trier’s Antichrist, the sensation (not in a good way) of this year’s Cannes festival. Once again, the central idea is the pornography of grief — together with some pornography of a more traditional sort — conceived and presented to us in as much and as harrowing detail as possible as an excuse for a popular theologian’s desire to be rude about God.

At least Mr Von Trier has a somewhat bigger idea than, simply, God’s non-existence. He is trying to explain how it is that some men seem to like torturing or killing women — a subject which his own filmography (Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, Dogville) suggests is rather an urgent one for him. Antichrist begins with the death of a child to answer the birth of the Child in the Christmas story, and in both a new world begins. But in Mr von Trier’s movie, it is not a redeemed but a damned world in which nature, in the form of a fox, tells us that “Chaos reigns” Actually, if nature tells us anything, it is that chaos does not reign, and the rationalist temptation proves too much for Mr von Trier himself when he tries to explain the cruelty in human nature. But the pleasures of portraying the tortures that the dead child’s grieving parents, played by Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg, devise for each other are like those of Charles Darwin’s near-hysteria of grief in Creation: that is, a kind of compensating emotional immensity to fill the vast hole of God’s absence.

The purpose here, as in other apocalyptic movies of the season, like 2012 or The Road, is ultimately political. The emotion is a catspaw for some rationalist, like Mr Bettany’s Darwin, to remake the world in his own image and so to play God himself. Beckett laughed at this impulse in the joke about the tailor who, scolded for taking weeks to make a pair of trousers when God took only six days to make the world, said: “Look at the world and look at my trousers!” But we’ve lost the knack of such laughter. Even so fine a film-maker as Michael Haneke purports in his new picture, The White Ribbon, to explain the First World War by — you’ll never guess — the strict parenting style of pre-1914 Germany! In other words, it’s our old friend, “repression.”

That kind of thing is the oldest of old hat in the movie business, as in other areas of culture. “Those to whom evil is done/Do evil in return,” wrote Auden to explain the Second World War. It is a kind of intellectual pride, like Mr von Trier’s, in understanding evil, together with a facile political sense of how the evil might be abolished — say, by not punishing misbehavior in children. When is despair not despair — and therefore “bracing”? When it is the vanity of intellectual superiority.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.