The End of History

From The American SpectatorThe Don and Friends

Ondi Timoner’s We Live in Public is a movie about Josh Harris, a man who made $80 million in the first dot-com boom of the 1990s and invested it, with what has since come to seem truly spectacular ill-judgment, in becoming what he proudly describes as an “artist.” His art was displayed in what was called the “Quiet” project, which consisted of rounding up a hundred or so people, putting them in a sort of dormitory full of cameras in Manhattan and filming the results. He charged them nothing for their room and board — plus quite a lot of free sex, target practice with automatic weapons and video-game time — except for their signatures on a waiver of their rights to their own images. These images have so far proved worthless, unless you count the excerpts in this movie. Not too surprisingly, Mr Harris soon went bust.

After a spell as an apple farmer, so Ms Timoner’s documentary tells us, he has now moved to Ethiopia, where his artistic vision must be coming to resemble that of Evelyn Waugh’s Mr Todd in A Handful of Dust — or perhaps Conrad’s Mr Kurtz in Heart of Darkness. All the same, I’m not sure that we should be too quick to dismiss him as a prophet of the “art” of the future. So, at least, I have begun to think since two recent theatrical events have brought home to me the extent to which the art of the past is done for — like the past itself. It’s history. The postmodern giggle has taken over that now moribund culture which owed so much to the now-defunct Western honor culture.

The first of these events was a production of the Mozart-da Ponte opera Don Giovanni at the New York City Opera. Musically, this was as good a production of the opera as I have heard, and both the conductor, Gary Thor Wedow, and the singers, including Daniel Okulitch as the Don, Jason Hardy as Leporello, Stefania Dovhan as Dona Anna and Keri Alkema as Dona Elvira are to be congratulated. But they must also be congratulated for singing their parts while negotiating the bizarre stagings of the director, Christopher Alden. Set in what seems to be a cross between a bus station and a store-front church, the production subverts the honorable conventions that are at the heart of the opera and makes it instead into a psycho-sexual erotic fantasy.

As a result, the element of black humor in the original — which begins, after all, with a rape and a murder — becomes the whole point of the production instead of an ironic commentary on the moral drama. The sexual tension between Donna Anna and Don Ottavio (Gregory Turay) and Donna Elvira and Don Giovanni is brought out into the open, as Anna yields to an importunate Ottavio and Elvira paws at Leporello in disguise as Don Giovanni. When in the final scene Don Giovanni welcomes a new dish at the dinner table, which is also the Commendatore’s coffin (!) — Ah che piatto saporito! — it is the maidservant he is referring to, on whom he proceeds, apparently, to perform cunnilingus.

The frustrated longing so essential to the character of Don Ottavio and the sad adumbration of her emotional priorities by Donna Anna in rejecting him are thus made as ridiculous as “repression” always is in the po mo telling. The Commendatore (Brian Kontes) is killed not in an affair of honor but when Don Giovanni smashes his head against the wall of the bus station while a chorus dressed in 1930s-style clothes looks on impassively. The blood stain there remains visible throughout the opera, a reminder that honor has been rendered irrelevant by mere passion. Nor is there any hellfire or damnation. The Commendatore is not a statue come to life but a singing corpse. The Don’s fate is thus no worse than death — until he reappears in the final scene as he was in the opening one, apparently having got off scot free.

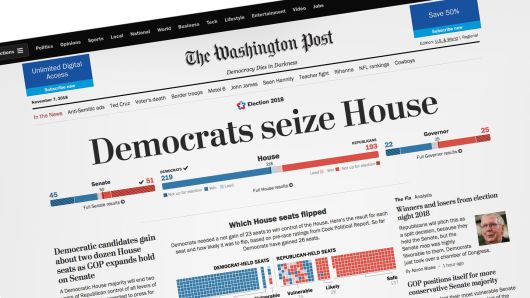

|

The other event was the production of As You Like It by the Shakespeare Theatre of Washington by Maria Aitken, who did last year’s version of The 39 Steps on Broadway that I wrote about in this space at the time (see “No Room for the Gentleman Amateur” in The American Spectator of March, 2008). Obviously I didn’t expect much from such a quarter, but the production started out well. In particular, both the girls, Francesca Faridany as Rosalind and Miriam Silverman as Celia, were terrific, I thought, and John Behlmann’s Orlando wasn’t terrible either, and at least very likeable. As with Don Giovanni, there was obviously real technical skill here. But after representing the court as a grim Puritan prison — unfair both to courtiers and Puritans — the production transferred us to an American Arden which at first tried, not without success, to keep up the pastoral theme in the primeval forests of North America with Indians and colonists but soon degenerated into undisciplined parody.

The idea was that we were supposed to be in Hollywood in the 1930s, and the mixing up of historical periods took us from the Puritan Fathers to the revolutionary period to the Civil War to the 1890s gold rush to the Roaring 20s with the same characters in very different period costumes in every scene. All coherence was lost, and Shakespeare just became the jumping off place for a bunch of irrelevant jokes. When Floyd King as Touchstone outlined the seven degrees of the lie by which courtiers may pretend to be valiant without (quite) having to fight a duel he naturally assumed that his audience would find the multiple and technical references to 16th century ideas of honor boring and incomprehensible and so covered for the meaninglessness — to him as to everyone else — of Shakespeare’s words by offering a gratuitous impersonation of Groucho Marx in delivering them. This was enough to make the obliging audience laugh at him — though not, of course, at Shakespeare.

At least they found it fun, which was all that Ms Aitken was going for anyway. The production had no more to do with Shakespeare than the New York City Opera’s Don Giovanni had to do with Mozart and da Ponte. It’s no big deal, I guess, for those who don’t mind as much as I do being cut off from the past by the prison of our own assumptions about the world, but it is at least a reminder that, as the art of the past is a closed book to us, art in general is no longer to be seen as a representation of reality — as it was in the Western tradition right up through the modernists. Reality is too hard. Instead, it creates its own reality — also known as fantasy. Another way to put this would be to say that all art is now performance art, which sounds a lot like what Josh Harris was trying to tell us back in 1999.

His insight was taken up, though without any acknowledgment, by Neil Gabler just before Christmas when, inspired by the Tiger Woods saga, he wrote in the newly revamped and frankly left-wing Newsweek that the celebrity culture itself ought rightly to be seen as a work of art. To Mr Gabler, recanting what he now describes as the “trivialization” of celebrity in Life the Movie, which came out when Mr Harris was putting together the “Quiet” project,

celebrity isn’t an anointment by the media of unworthy subjects, even though it may seem so when you think of minor celebs such as Spencer Pratt and Heidi Montag, or Levi Johnston, or the gate-crashing Salahis. It is actually a new art form that competes with — and often supersedes — more traditional entertainments like movies, books, plays, and TV shows (and the occasional golf tournament), and that performs, in its own roundabout way, many of the functions those old media performed in their heyday: among them, distracting us, sensitizing us to the human condition, and creating a fund of common experience around which we can form a national community. I would even argue that celebrity is the great new art form of the 21st century.

“Great” in this context I assume means big — as in Great Britain or great toe — which is its normal meaning in Shakespeare, by the way. But the cost of adopting celebrity gossip as our great new art form is to banish at once both older art forms and the other kind of greatness, which was so often supposed to go with them. What else was Christopher Alden doing by taking away Don Giovanni’s tragedy and terror and making him into a rock star avant la lettre? What else was what Maria Aitken doing with As You Like It but converting Shakespeare into an extended essay in celebrity-worship? The idea in both cases was to make the works “accessible” to modern audiences — which sounds like a good idea until you reflect on what it takes to make something accessible to those with no interest in history.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.