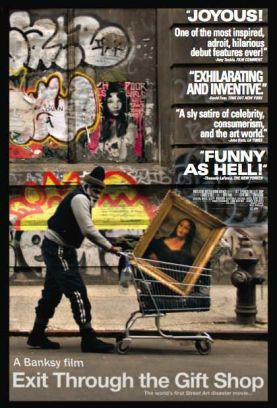

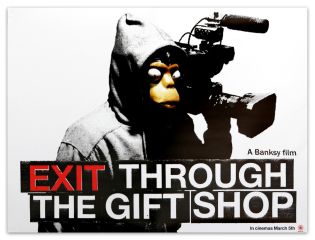

Exit Through the Gift Shop

Back in the 1970s, the late, great Michael Wharton, a British satirist who wrote for The Daily Telegraph under the name of “Peter Simple,” made fun of some pretentious artsy types who had been noticing a graffito on a wall at the Paddington rail station in London. It read, in its entirety, “Far away is close at hand in images of elsewhere.” Your guess is as good as mine — or anyone else’s — as to what that might mean, but it was precisely that vaguely evocative meaninglessness which attracted a certain kind of literary sensibility. Peter Simple hilariously claimed that “Dr Anita Maclean-Gropius’s monumental catalogue raisonné, ‘The Master of Paddington’ (Viper and Bugloss, £65), published last year, dealt in detail with all the works confidently or tentatively attributed to the Master and his School.” This monumental work of scholarship, he went on, “was, of course, savaged in a long review by Dr J.S. Hate, Keeper of Graffiti at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in the British Journal of Graffitology.”

As usual, the satire was not much ahead of the reality. Thirty years later, the Telegraph published a rapturous article about “the Michelangelo of Graffiti” whose “street art,” reproduced in a suitably vendible form, was being shown at fashionable galleries and knocked down for fashionable prices in the six figures to fashionable people. The artist, who deals in striking imagery and trompe l’oeil effects rather than piquant poetry, calls himself “Banksy,” and he owes his international artistic super-stardom to the combination of mystery, street-cred and fashionable political views — though his anonymity may have been compromised two years ago by an article in The Times of London which identified him as Robin Gunningham, a former public schoolboy from Bristol. This has never been confirmed, however, and the historical Robin Gunningham, as we might call him, is said to have disappeared.

Now the School of Banksy is branching out into film production with Exit Through the Gift Shop, of which Banksy himself is listed as director. He also appears — or someone claiming to be he does — on the screen in a hooded sweat-shirt that shadows his face and with an electronically distorted voice. On his first appearance, however, he tells us that the picture is not about him and his guerrilla art, except in tangential ways. Instead, he introduces us to a cheerful Frenchman with an obsessive personality called Thierry Guetta who, so Banksy assures us, is a lot more interesting than he is. Also a lot more available to the camera. And I mean a lot. Thierry got his start selling old clothes to people in Los Angeles who like to dress up in old clothes. There were enough such people there to have made him successful and supported his hobby of recording the nocturnal activities of graffiti artists on video tape. Eventually, he attempted to turn his old video-tapes into a documentary of his own titled Life Remote Control but as Banksy, now playing critic, tells us, “It was s***.” He realized, he says, that “Thierry was not a film-maker, just someone with mental problems who happened to have a camera.” The picture was well-named, however, as it produced the impression of someone’s “constantly switching a TV remote control between 900 different channels.”

|

Thereafter, Thierry himself decided to become a “street artist” calling himself “Mr Brainwash” and subsequently to follow Banksy into the legitimate art world by staging a big L.A. exhibition of his mass-produced, sub-Warholian masterpieces titled “Life is Beautiful.” The exhibition’s apparent success — I have not checked up on this — is at least a tribute to his genius for publicity, if not his talent. He prevailed upon Banksy to provide the exhibition with a blurb (“Mr Brainwash is a phenomenon, a force of nature — and I don’t mean that in a good way”) and subsequently to direct this film, which is all about the force of nature in a (mostly) good way and will, therefore, doubtless contribute to keeping his prices up, if not quite so sky-high as Banksy’s. Thus, the movie is about a con-man of a familiar kind, an entrepreneur of conceptual art and his own genius in producing the concepts, and it is itself a con.

The most interesting thing about it is that Banksy gives a sort of semi-apology for this at the end. “Andy Warhol,” he tells us, “took cultural icons and repeated them until they became meaningless, but he did it in an iconic way; Thierry made them really meaningless.” Then we cut to Thierry himself grandly observing: “Only in time will you see if I’m a real artist or not.” Back to Banksy again. “Maybe it means that art is a bit of a joke. I used to encourage everybody I met to make art. I used to think everyone should do it. I don’t do that so much anymore.” Later, a screen card pops up with the closing credits reading: “Banksy will never again help anyone to make a documentary about street art.” That seems a promise worth holding him to, assuming for the moment that you can hold a superhero to anything. Yet in the movie’s defense, I would have to say that you are never likely to see a better example of how, in the art world as elsewhere, the principle of “style without substance” has become the new substance. Peter Simple, I feel sure, foresaw it all.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.