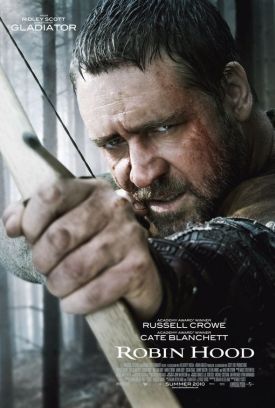

Robin Hood

There’s a funny moment in Ridley Scott’s new version of Robin Hood — almost the only one among these no-longer very merry men — when Robin (Russell Crowe) and Maid Marion (Cate Blanchett) are getting to know one another, and Marion has just told him of her brief marriage to Sir Robert Loxley (Douglas Hodge), the son of Sir Walter Loxley (Max von Sydow) of Pepper Harrow, Nottingham. After only a week of married life, her husband had gone off to the Holy Land with King Richard for a decade of crusading, where he, like the King, had met his death. Now, at Sir Walter’s instance, Robin has agreed to impersonate his now-dead son, Marion’s husband, so that the estate of Pepper Harrow will not be confiscated by the crown on his death. Robin, a lowly yeoman and archer, had known Sir Robert in the King’s army and says of him to his widow, “A good knight.”

“It was short but sweet,” replies Marion.

“No, I meant: he was a good knight,” explains Robin. “A knight at arms.”

“Oh, yes, to be sure. Knight at arms.”

It’s all part of a classic Hollywood “meet-cute” setup which starts from the moment that, seeing her from behind, Robin addresses her as “girl” and receives a blushing rebuke for failing to see that she is, as she insists, far past her girlhood. The moment of her coyness and embarrassment is so movieish, as is the moment when Robin, come to deliver the news of her husband’s death, is invited to dinner by her father in law, and requires her to help him off with his chain mail first. As his magnificent physique stands revealed before her, we are invited to speculate on what this long unhusbanded woman must be thinking. Or, when they must share a bed-chamber to persuade the servants that this is really Sir Robert come home to his wife and Marion warns: “I sleep with a dagger. If you ever move as to touch me, I will sever your manhood.” Ha ha. We know from the movies that all this classic movie-courtship means that they will soon be together.

As is usually the case these days, this breaking of the frame and fracturing of the illusion that this is about 12th century England rather than present-day Hollywood, is deliberate. The real 12th century or anything approximating to it, so Mr Scott and his screen-writer, Brian Helgeland, presumably imagine, would have been deadly boring to the pimply teenagers who are their hopeful audience. For the same reason, Mr Scott tarted up the Middle Ages in Kingdom of Heaven (2005) and Mr Helgeland did the same in A Knight’s Tale (2001). Children these days expect the past to be made “relevant” to their lives, not their lives to be put in touch with the past as it really was.

It is in some ways amusing to read the film as an allegory of the tea-party movement and recent American politics. King Richard (Danny Huston) thus becomes George W. Bush, a warrior king but one who foolishly squandered his resources on an ill-advised Middle Eastern war that turned out to be the ruin of him, bankrupting the country and leaving it to the tender mercies of a young and inexperienced successor, his brother John (Oscar Isaac), who, like President Obama, is determined not to allow the profligacy of his predecessor hinder his own plans for taxing the people until the pips squeak and spending the money on his own pet projects — meanwhile leaving the country defenseless against a foreign enemy drawn to make surreptitious war by the perception of his weakness and domestic distractions. The foreign enemy in this case is France, which mounts an invasion across the channel unrecorded by history in Normandy-style landing craft. Obvious allusions to Saving Private Ryan — with arrows taking the place of bullets — are both an homage to Steven Spielberg and a further reminder of the deliberate movie-fakery. So is poor Miss Blanchett in a full suit of armor laying about her with a broadsword on the beach.

There isn’t one interesting character in this movie. All are recognizable stock figures from a thousand similar and similarly pseudo-heroic sagas. But I don’t think this is by inadvertence or incompetence either. To make anyone interesting, or even recognizably human rather than a movie type, you would break the spell and remind the audience of what is missing, which is the link to reality that even the most jaded post-moderns among us still sort-of expect from movies. We imagine, at least if we’re not thinking about it too closely, that the movie will resemble real life in certain important respects, and Mr Scott is here to tell us that that ain’t happening with his movie — and to scold us for continuing to expect it to happen. Like the remarkable closing credits, the whole film is absurdly over-produced. But there is a reason for this, I think. It is that Ridley Scott needs constantly to remind us that this is not only fantasy but a particular kind of fantasy, a movie fantasy set in a movie utopia and peopled by movie archetypes — not to say stereotypes.

For the tea-party stuff is just a tease. By the time you get to the end of the movie’s 140 minutes, you realize it is just another progressive fable. Robin turns out to be the son of the guy, a stonemason, who wrote the Magna Carta — here represented as a 19th century rationalist’s design for a perfect political system — a generation before the barons, with the indispensable help of Robin, sought to impose it on King John. Robin adopts as his own Sir Walter’s meaningless but curiously utopian-sounding motto: “Rise and rise again until lambs become lions” and the defeat of the French is followed by a retreat to the Greenwood where, on Marion’s account of it, there is “no rich no poor, but fair shares for all at nature’s table.” There is also an allusion to Peter Pan and the lost boys with Marion in the role of Wendy and Robin that of Peter. We’re home once again, folks, back in Movieland. I’m not quite sure how that’s happened, but somehow, that’s the only place today’s audiences ever want to be.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.