Rebels Without a Clue

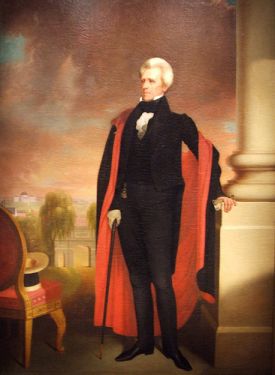

From The American SpectatorAndrew Jackson, Old School Version

Say what you like about The New York Times, its Arts section can save you a lot on theatre tickets, particularly if, like me, you have to come from out of town to see anything that’s new on Broadway. Not that any ordinary person would want to see much of anything that’s new on Broadway. The audiences there are becoming as specialized as the performers, and neither appears to have anything to say to Conservative Tastes. But the indefatigable Times critics, by keeping us current with all the crazy stuff that the creatives are getting up to are often good for a laugh even as they spare us the necessity of wasting our time on it.

According to Ben Brantley, for instance, a new rock musical called Bloody Bloody [sic] Andrew Jackson portrays our seventh president as a rock star — and not a metaphorical rock star like our 42nd and 44th presidents either. This is a literal, if fictional rock star, “poured into a pair of tight black jeans and fiercely embodied by a microphone-riding Benjamin Walker.” Et pourquoi? To demonstrate, says Mr Brantley, that “this country’s relationship with its president is always deeply and irrationally personal.” I don’t know whether or not that’s true but, insofar as it is a statement about history, the musical’s blatant attempt to dress up the past as if it were the present can hardly be the best way of persuading us.

What I think he must mean is that the authors (Alex Timbers and Michael Friedman) of Bloody Bloody have created history of a kind that is now often called “counterfactual” — imagine what you’d get if you put together history’s violent and passionate populist Andrew Jackson with today’s celebrity culture — but which I prefer to call by its right name, which is fantasy. Andrew Jackson could not have existed at the same time as the celebrity culture. The precondition of the celebrity culture’s existence is the non-existence of Andrew Jackson, or anyone remotely like him. That impossibility is precisely the provocation the celebrity culture requires to fantasize about such a fabulous monster as a rock-star Old Hickory offering, as Mr Brantley puts it, “the ultimate promise, the one you truly want to hear from anyone who aspires to lead your nation: He solemnly swears to give you the best sex you’ve ever had.”

It is not possible that the author of those words actually believes this is “truly” what you, me or anyone else wants to hear from an aspiring national leader, so we must suppose that this is just an answering rhetorical flourish to that of the show itself. Once you have taken down the barriers against fantasy, then everything becomes fantasy, including The New York Times review of it. Mr Brantley adds that, “though the deft and daft cast members would all seem to be past college age, their performances have the sensibility of a precocious, conflicted 14-year-old who can say what he really wants to only by pretending that he doesn’t mean it.” I’m pretty sure he means this as praise.

Two weeks later, his Times reviewing colleague Charles Isherwood wrote of another much-praised musical, American Idiot, based on the musical album of that name by the punk band Green Day, that “the emotion charge that the show generates is as memorable as the music. American Idiot jolts you right back to the dizzying roller coaster of young adulthood, that turbulent time when ecstasy and misery almost seem interchangeable states, flip sides of the coin of exaltation. It captures with a piercing intensity that moment in life when everything seems possible, and nothing seems worth doing, or maybe it’s the other way around.”

You’ve got to wonder what’s going on with these twin musical celebrations of adolescent angst. Has New York theatre-land suddenly been transported back into the late 1960s when such stuff was all the rage? Not really. Youth culture today, now that there is no culture but youth culture, has become a largely reflective phenomenon. The middle-aged and old who remember the youth culture of the 1950s and 1960s demand that their children and grandchildren imitate their aboriginal act of cultural rebellion, and at least some of the young are answering the call — even as there are fewer and fewer things to rebel against. That’s why the rebellion so often ends in self-destruction and celebration of mere victimhood. The principal hero of American Idiot, for instance, becomes a heroin addict.

The youth culture is actually quite old — more than a century. We missed the hundredth anniversary last year of the Futurist Manifesto of the Italian poet Filippo Marinetti which, along with the worship of youth, could be said to have spawned a considerable portion of the modernist movement, the First World War, Communism, Dada, Fascism and the Jazz Age, not to mention the heirs of all these things in the 1960s who thought they had invented the “generation gap.” Their soi-disant “revolution,” however, was turned inward, in the direction of self-liberation. Rebellion was now only the rebellion of self and appetite against society and society’s traditional expectations of us.

Paradoxically, society’s traditional expectations now include the expectation of rebelliousness in the young. And just as America’s youth once answered the call of honor in the defense of their country, now they answer the call of self-realization with the same mixed feelings of trying to live up to their elders’ expectations of them while rather resenting them for having such expectations in the first place. This is what we are seeing, I think, as we watch the unofficial culture continue its takeover of the official, begun back in the ‘60s. Now Broadway musicals, those one-time affirmations of bourgeois virtues, have become celebrations of youthful attitudinizing. What are already or promise to become such contemporary theatrical perennials as Grease, Hair, Rent, Urinetown, Movin’ Out and Spring Awakening (which has the same director, Michael Mayer, and the same star, John Gallagher Jr., as American Idiot) re-enact the primal myth of our time, the same one that many if not most rock groups also portray, that of more or less anarchic and undirected youthful rebellion — the point of which is to be politically “hip” without being politically coherent.

Such myth-making is generally content to reduce what little dramatic conflict there is to a symbolic level. Thus, the “idiot” of American Idiot is supposed to be George W. Bush, since the former president’s idiocy can be taken for granted in the rarefied world of the American theatre today. An icon of Mr Bush also appears in Lucy Prebble’s Enron, just transferred from the West End of London and also reviewed by Mr Brantley, who is not offended by having his political prejudices reinforced — along with the moralization of political culture that was such a feature of the Bush years. Ms Prebble’s simple-minded morality play brings people in dinosaur costumes onto the stage in order to illustrate her point that the leaders of the doomed company were “raptors,” and the idea inspires Mr Brantley to enthuse about Stephen Kunken’s portrayal of Andy Fastow:

The vision of Fastow — a necktie wrapped around his head — and his raptors in his inner sanctum, just before Enron goes boom, brings to mind a war-warped, jungle-fevered character out of Apocalypse Now or The Deer Hunter. It’s a hilarious, scary image and one of the few in Enron that suggests the real heart of darkness meant to be beating at its center.

|

A company which sought to make money by new and innovative accounting practices that broke the rules and finally broke itself is now to be seen as the “heart of darkness” — a place of murder and unfathomable savagery? Only in New York, kids. Only in New York. Or at least only in the media and artistic culture headquartered there.

The “raptors” are as much painted devils in this pantomime as George W. Bush, and both are symptomatic of the larger incoherence of the institutionalization of rebellion. Another example is Exit Through the Gift Shop, a documentary film said to be by the otherwise anonymous graffiti artist known as “Banksy.” Banksy made his name by such acts of “guerrilla art” as chaining an inflatable dummy of a Guantánamo Bay prisoner to a fence at Disneyland, but he is now a bona fide star of the art world. His “street art” originals now sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars and are regularly given gallery shows.

One such took place in his home town of Bristol, England, last year and was titled “Banksy Versus Bristol Museum.” Naturally it was held at Bristol Museum. Two weeks after it opened and a few hundred yards up the road, his latest elaborate graffito — which, according to the Daily Telegraph “shows a naked man hanging from a window ledge with a husband and his scantily-clad wife peering from within” — was vandalized. The city council promised to restore it. Freedom, heyday! Heyday, Freedom!

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.