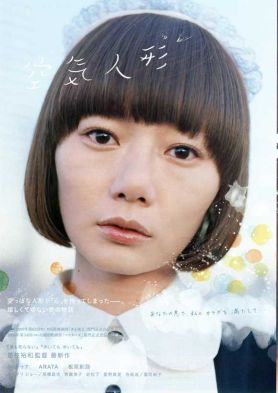

Air Doll

I had great hopes for Air Doll (Kuuki ningyô) by the Japanese director, Hirokazu Kore-eda, of the wonderful After Life (Wandâfuru raifu) of 1998. That was a sort of metaphysical romance, like Groundhog Day, in which a hitherto undiscovered spirit-world inhabited by the dead proves the locale for moving and persuasive life-lessons designed for our world. This kind of thing is very hard to pull off, however, and Air Doll, which is more of a parable than a romance, doesn’t quite succeed. Or at least I don’t think it does. But it should also be said that this is one of the very few movies I have seen in 20 years of reviewing of which I don’t quite know what to make — or even whether or not I like it. It is possible that I am missing some important pieces of the puzzle and need to go back and see it at least a couple of more times before pronouncing on it.

My immediate reaction, however, is that it goes on for too long, tries to do too much and so ends up being too boring. The best bit is a brilliant comic scene stranded in a sea of philosophizing. As for the philosophizing itself, the parts that I got were not hard to get, and, having got them, I didn’t think they needed to be dwelt on so much as they were. The parts that I didn’t get I guess had to do with a breakdown of formal boundaries. What might have been a beautiful and moving parable proves unwilling to remain within its parabolic boundaries and tries instead to become a comic book fantasy of a now too-familiar kind, a sort of feminist updating of Pinocchio for the age of utopian sex.

A waiter named Hideo (Itsuji Itao) possesses a life-sized plastic sex doll whom he names Nozomi. He dresses her in a maid’s uniform and sits her down at the table with him when he comes home to eat his own humble evening meal and proceeds to talk to her about his day at work. There ensues one quite revolting sex-scene between them in which the authentic sounds of flesh rubbing against plastic may be meant as comedy but only added to the disgust, of this viewer at any rate, at such a degrading spectacle. Yet in retrospect I think the unpleasantness of the opening might have led into more profitable avenues than does what actually happens next, which is that the doll comes to life and begins talking to us in voiceover. Her first word is “beautiful” — addressed to the world through Hideo’s window. She also tells us that “I am air-doll, a substitute for handling sexual desire.” As if we didn’t know.

As I say, this kind of thing is extremely hard to bring off — at least partly because, once you start off with what amounts to a miracle, there’s really no place to go from there. Everything else is anti-climactic. Now played by the striking-looking actress Doona Bae, Nozomi, wanders off into the city while Hideo is at work and finds a job in a video-rental store where she meets a young man named Junichi (Arata) and falls in love. Junichi discovers, through an accident, that Nozomi contains nothing but air beneath her pleasing surface and affects a similar emptiness of his own. This turns out not to be true. She also meets a philosophical old man, a former substitute teacher (get it?) who proclaims such emptiness to be the normal condition of everyone in the city, these days. Oh dear. Nozomi returns to Hideo and resumes her doll-like form at night.

There is thus a kind of parody of a drama of love, betrayal and infidelity given a distinctive character by Nozomi’s dawning self-awareness and childlike wonder at the beauty and unfamiliarity of the world, which we look at through her eyes. But a little of this goes a long way, and we turn with some relief to a wonderfully bizarre comic scene when Nozomi comes home and finds Hideo in bed with a different doll. Having found a heart, as she tells him — the first he is aware of it — she has also found heartbreak. “What do you like about me?” she asks Hideo like any betrayed and reproachful wife. “You don’t know, do you? Even Nozomi is your old girlfriend’s name.”

“You read my blog!” cries Hideo.

“It doesn’t have to be me, right?” she asks him. It’s an absurd question, coming from a doll, but one that is naturally inseparable from the humanity that has been somehow called forth in her. Of course, as we realize and she cannot, what Hideo likes about her is just that it doesn’t have to be her — that she has no identity apart from that which he projects onto her with his sexual attentions. Similarly, when the (married) video store proprietor (Ryo Iwamatsu) blackmails her into a sexual encounter by threatening to tell Junichi about Hideo — or is it Hideo about Junichi? — he whispers to her in medias res: “You do this with anybody, don’t you? The dirty girl with no heart and unlimited sexual pliancy is both attractive and repellant and much better without the heart she doesn’t know what to do with.

Meanwhile, though Junichi assures her that, so far as he’s concerned, she’s “not a substitute for anyone,” he gets turned on by deflating her and then blowing her back up. As this is for her an act of love, she offers to do the same for him. He aspires to doll-hood, just as she aspires to humanity. But humanity is what everyone around her is fed up with. At the end of the last scene with Hideo, she reproaches him for lusting after a doll, either herself or her own substitute, in a recognizably human way: “You’re sad that I found a heart,” she tells him. “I’m annoying.”

“It’s not you who are annoying,” he calls after her as she runs out the door. “Humans are!”

I think the movie would have been better if it had stopped here instead of pushing the boundaries of its limited concept to encompass such philosophical reflections on the part of the (literally) air-headed doll as this. “It seems life is constructed in a way that no one can fulfill it alone. Life contains its own absence, which only an other can fulfill. It seems the world is the summation of others, and yet we neither know nor are told that we will fulfill each other. We lead our scattered lives, perfectly unaware of each other. Or at times, allowed to find the Other’s presence disagreeable Why is it, that the world is constructed so loosely?” And why is it, I want to ask her, that you wear a helmet when you ride on the back of Junichi’s motorbike? Both her and Mr Kore-eda’s reaching after significance like this rather spoils what is good about the movie, in my view — but that may only be because I cannot reach so far myself.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.