Hugh Hefner: Playboy, Activist and Rebel

The other day as I cast my eye over The Guardian, my poor recourse since The Times of London retreated behind a pay-wall, I noticed an obituary of a musician named Robbie Jansen whom the obituarist described as a “South African alto saxophonist who fought apartheid through his music.” Well, good for him, I thought. But isn’t being a musician, and presumably a good one, enough for anyone to be remembered for? Do you also have to fight apartheid through your music for your life to make an impression on the world sufficient for The Guardian to make a note of your existence? Quite possibly you do. At any rate, the media culture prefers to honor those who have served heroically (on the right side, of course) in the culture wars in addition to (or perhaps instead of) just being good at what they do.

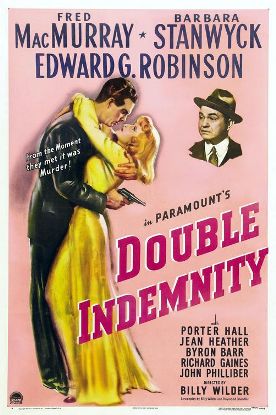

I thought of Robbie Jansen, though I had not heard of him before, when I saw Hugh Hefner: Playboy, Rebel, Activist by Brigitte Berman who, if she isn’t a paid employee of Hugh Hefner Enterprises might as well be. Of course, as everyone has heard of Hugh Hefner — unlike Robbie Jansen — his right to be memorialized is unquestioned, as is the fact that he was a business genius during the 1950s and 1960s who was the first to spot the emerging market for naked female flesh packaged for home consumption by strangers — especially teenage boys of the baby boom, like me. As Ms Berman’s account of his career as “Mr Playboy” makes clear, our ideas of sophistication and glamour were largely shaped by Hef and Hef alone. Yet from her movie, with its ludicrously pretentious title, you’d think that Playboy was the least of him, and that he was not just a shrewd skin-merchant but a cross between Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Moses and Jesus Christ, so noble was his liberation of — well, randy males who had had enough of “repression” and were looking for some guilt-free fun.

In this, of course, she is playing to the Hollywood version of the media culture and especially to the media’s mythologization of the last 60-odd years. Hef was there, she tells us, manning the barricades at all the right moments of the revolution, from his heroic opposition to segregation and racism, to his determined fight against sexual “repression,” women’s as well as men’s, to his defiance of the “witch-hunts” of the House Committee on Un-American Activities to his opposition to the Vietnam War. Naturally, if Hef was on the right side on all these matters his opponents were on the wrong side — which meant that being against the Playboy Philosophy [sic] also amounted to being on the wrong side. Hence Hef’s reference to “sexual McCarthyism” — an indescribably silly characterization of traditional standards of public decency but one self-evidently designed to appeal to that same media mythology.

Among Ms Berman’s clips of Mr Hefner’s heroic public career there is one in which he says of the congressional communist-hunters that “this notion of defining your neighbor by what his politics were was abhorrent to me.” Indeed, he appears to have thought it virtually Nazi: “I thought we were becoming the people we had defeated.” But isn’t his calling those who disagree with him sexual McCarthyists a case of defining his neighbor by what his politics are? Officially, of course, Playboy and its defenders were on the side of “freedom” and against the oppressive laws or community standards they had been written to defend which stood in the way of sexual freedom. But it turns out that freedom has to adopt its own methods of oppression in order to silence those who don’t like what the free people are doing. It’s all a question of freedom for whom, and Mr Hefner wants us to know that he is on the side of freedom for pornographers.

Oh, and communists, too, whom he calls “liberals” — as in the charge that Ronald Reagan as president of the Screen Actors’ Guild had “liberals” blacklisted. Likewise, he says that lovable old Pete Seeger “was considered a revolutionary.” Too bad nobody thought to ask Pete — who, age 90 and looking remarkably spry, appears on-screen to offer Hef and his magazine his imprimatur — if he considered himself a revolutionary, since so far as I know he has never made any secret of the fact either that he was a communist or that his communism, like everybody else’s in those days, was a revolutionary philosophy. Come to that, Hef himself could justly be called a revolutionary, but his modesty stops short of such a claim.

More interesting than what is included in this film is what is left out. We are told that the 1959 Chicago Jazz festival heralded the arrival of Playboy as a mainstream publication, which may indeed be true. Hef tells us that it was at about this time that “I re-imagined myself; I was Mr Playboy” — that is, the public apologist for new ways of thinking about sex (among other things) and not just a pedlar of smutty magazines. But the evolution of the magazine itself is hardly mentioned. Visually, we are reminded of it by the sudden appearance of unveiled pubic regions some time in the 1980s — had it really not happened before that? — after the relatively demure decades of mere breast fetishism. But there is no explanation or even notice taken by the commentary of anything being different. There is a brief reference to the murder of Dorothy Stratten but nothing else so much as to hint at anything sordid in the immaculate, freedom-loving 60 years of exploiting young women.

Stephen Holden, reviewing the movie in The New York Times writes that it

ultimately makes a strong case for Mr. Hefner as a consistent and underappreciated champion of racial equality and sexual emancipation. But that emancipation had a dark side. There is simply no getting around the fact that Playboy, for all of Mr. Hefner’s assertions that it helped level the playing field in the battle of the sexes by affirming women’s right to pleasure, also objectified women as compliant, ornamental playthings. As for the man who invented it all, he remains a mystery in the film, living out his days in sybaritic bliss.

Maybe the problem lies in that word “objectified” — a feminist borrowing that has never made any sense to me. Of course women become “objectified” whenever sex is involved, since nature designed them that way — as objects to attract men. In this very limited sense you’ve got to agree with Mr Hefner in his reply to a feminist complaint that he limits his understanding of humanity to its “animal” nature. “Of course we’re animals,” he says. “What’s left? Vegetables? Minerals?” But this inescapable animality is the reason why “sex” used to be, before people like Hugh Hefner came along, something that only existed under the tightest sort of social circumscription — and why that social circumscription in the form of marriage laws and the enforcement of standards of what were once regarded as public decency were good for women: because they very strictly limited the circumstances of that objectification.

Women as public creatures, forced by the same laws and customs to dress modestly, escaped the evolutionary prison of their (and our) animal nature and became people, albeit people who were in part defined by their non-masculinity. Doing away with that social and legal differentiation of the sexes in the name of equality, therefore, naturally went hand-in-hand with a shocking increase in the amount of objectification. Or, to put it another way, if you don’t like being objectified, try passing laws to jail people who get rich from objectifying you or your sex. Oh right, we tried that. Then along came Hugh Hefner and others like him to suggest that the people who did it were Nazis or McCarthyists and the whole pro-woman legal edifice came crashing to the ground.

You’d think it would have been a brave move for Ms Berman to put Susan Brownmiller, of all people, on screen to add her assessment of Hef’s career, and yet for some reason Ms Brownmiller doesn’t say any of this but only adds her two cents’ worth to the general feast of banality by noting that not all women have the perfect bodies of the Playmates. Do tell! A younger version of herself very slightly embarrasses Mr Playboy on the Dick Cavett Show by asking how he’d like to wear a bunny-tail, much to the delight of the audience, or at least its female members. I wonder why it didn’t occur to him to reply, “Do you think that anyone besides yourself and a few other embittered and unattractive feminists would pay to see it?” It would have been not only a witty riposte but also a reminder to her and everyone else who has forgotten it since just what sort of business he is in.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.