The Pursuit of Happiness

From The American SpectatorMy annual summer film series for the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. was this year presented jointly with and on the premises of the Hudson Institute and focused on the theme of the Pursuit of Happiness. For reasons too tedious to go into, there were only six films instead of eight this year, but once again they were meant in part to point a contrast between the movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age (1930-1960) and the age of dross that has come after it — and also after (not coincidentally) America’s Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Unlike the previous series, however, this one finds not such a stark contrast in the before and after. In some ways the later films are better than the earlier ones. I guess that post-revolutionary Americans are a lot more serious on the subject of the Pursuit of Happiness than they are on those of Heroes, Love or Crime, the subjects of the past three summers, and so are less inclined to trivialize it.

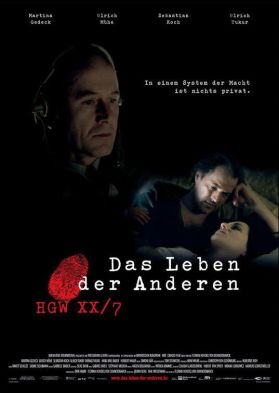

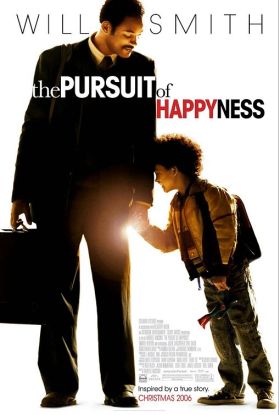

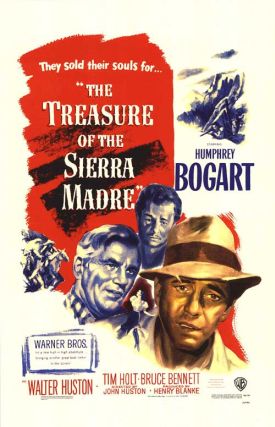

The pre-1960 films were My Man Godfrey (1936) by Gregory La Cava, starring William Powell and Carole Lombard, Christmas in July (1940) by Preston Sturges, with Dick Powell and Ellen Drew, Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) by John Huston, with Humphrey Bogart, Tim Holt and Walter Huston and Mr Blandings Builds His Dream House (also 1948) by H.C. Potter, with Cary Grant, Myrna Loy and Melvyn Douglas. Then, rapidly skipping over the intervening 54 years — which comprised heady pre-revolutionary, revolutionary and post-revolutionary days during which far too many people both in and out of Hollywood mistook pleasure for happiness — we arrived at Alexander Payne’s About Schmidt (2002), starring Jack Nicholson, Kathy Bates and Hope Davis and, finally, The Pursuit of Happyness (2006) with Will Smith, Jaden Smith and Thandie Newton.

At the most superficial level, it was impossible not to notice the extent to which the older movies assumed that the getting and spending of money was desirable in itself and a necessary component of the Pursuit of Happiness, if not (necessarily) the thing itself, while the later movies found the mercenary motive to be suspect. In the case of the movie called The Pursuit of Happyness this was not so true of the movie itself — though there were in the more-or-less true story of Chris Gardner (Will Smith) some hints of the inevitable cultural doubts and defensiveness about making money, at least in business — as in the reaction to it of critics who found it politically incorrect. “How you respond to this man’s moving story,” wrote Manohla Dargis in The New York Times, “may depend on whether you find Mr. Smith’s and his son’s performances so overwhelmingly winning that you buy the idea that poverty is a function of bad luck and bad choices, and success the result of heroic toil and dreams.”

|

Who indeed, in The New York Times’s view, could “buy” anything so preposterous? Ms Dargis’s sneering left her no room to notice that the chief feature of Mr Smith’s “winning” charm and that of his real-life son, Jaden Smith, who plays Mr Gardner’s son in the movie, and that without which the movie would certainly never have been made, was that he was black. And even then it probably wouldn’t have been made if not for its Italian director, Gabriele Muccino who, not having done an American movie previously, presumably was unaware of his cultural faux pas in suggesting that a black guy might succeed by dedication and hard work. This Hollywood-types would call “blaming the victim,” because it is supposed to imply that all the black guys who don’t succeed, or whose success is more limited than that of Mr Gardner, may have fallen short of such success for some reason other than white racism. They and their allies on the left therefore have a vested interest in believing that success is impossible for them.

Yet it is also true that even before the movies became racially aware in the 1960s, their view of success was somewhat ambivalent, to say the least. The country’s previous turn to the left during the Depression had created a certain amount of suspicion and dislike of the rich — “malefactors of great wealth” as President Roosevelt called them — that you can see hints of in My Man Godfrey. To be sure, the frivolous, insensitive and dysfunctional Bullock family in that movie were much more affectionately portrayed than their counterparts would be today — as the imminent resuscitation of Oliver Stone’s caricature villain, Gordon Gecko, in the sequel to Wall Street (Money Never Sleeps) is set to remind us this month — but they still have to be taught a lesson by William Powell’s Godfrey, the butler they hire from the shanty-town at the city dump who turns out to be a Harvard-educated aristocrat, just like FDR himself, slumming it among the allegedly “forgotten men” on the nation’s refuse pile .

That movie ends with Powell’s Godfrey starting up on the site of the dump and employing its former denizens a swanky nightclub which promises to be a nice little earner for him and to provide good jobs for them. The entrepreneurial spirit is alive and well, it seems, even if it has to be disciplined by social responsibility and good manners. In Christmas in July and Mr Blandings Builds His Dream House, however, success is seen as being, at least to some extent, capricious and uncertain rather than the product of ingenuity and industry. And, just as the heroes of those films could hardly be said to have earned the success that comes to them in the end, those of Treasure of the Sierra Madre are deprived of the success they have earned by what seems to them to be the caprice of “The Lord or Fate or Nature, whichever you prefer.”

|

We don’t know a lot about B. Traven, the pen name of the man who wrote the novel on which the film was based, but we do know that he was an avowed Communist, and a nice summary of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value is provided in the movie by Walter Huston, the director’s father, who won a Supporting Actor Oscar as the old prospector. It’s a wonderful movie, but it is also a reminder that Hollywood’s left-wing political culture, which has allowed a hack like Oliver Stone or a buffoon like Michael Moore to be hailed as great directors, reaches far back into the past, well before the revolutionary 1960s allowed the old left to emerge, blinking, from the hidey-holes into which the House Committee on Un-American Activities had driven them more than a decade before to join forces with the emergent new left. Bosley Crowther’s review of Treasure in The New York Times of January, 1948, saw it as a movie about “greed” just as Vincent Canby’s review of Wall Street in the same paper a month short of 40 years later cited Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is good” speech as the highlight of that movie. “After that, Wall Street is all downhill,” Canby felt.

“Greed” is of course the left-winger’s code word for the desire of someone other than himself or those belonging to such politically- or socially-approved groups as film directors or pop stars to make money. The word has lately made a comeback in the Democratic left’s attacks on the tea-party movement and its members’ desire just to keep the money they have already made, as if it were not really theirs in the first place but the presumptive property of those well-intentioned, “progressive” élites who see it as their job to help our benevolent President “spread the wealth around.” That sort of political tom-foolery has prevented us and to a considerable extent prevented our movies from examining the real problems of success, wealth and “happiness” in the sense that, I think, Jefferson intended it in the Declaration.

Yet every now and then one slips through the cracks. Such, I think, is About Schmidt, of whose qualities I think more highly every time I see it. Its eponymous hero, played by Mr Nicholson, could hardly be considered a symbol of “greed” even by Messrs Stone and Moore. He is just a mid-level insurance executive who has done well enough to be able to afford a nice home, a nice car, a comfortable retirement and an outsized Winnebago to enjoy it in — and yet he thinks, not without reason, that his life is a failure. At first he wonders if this is because he wasn’t ambitious (or, perhaps, “greedy”) enough to become someone “semi-important” in the world, but eventually he comes to see that his own pursuit of happiness has simply missed, as so many of ours do, the happiness that was there for the taking all along. That such a movie could be made in this day and age inspires thoughts of hope and change for Hollywood.

All these films are available on DVD and my commentary on them can be read on the Ethics and Public Policy website or on the “My Diary” pages of my website for the Wednesdays after the Tuesdays during June, July and August when the films were presented here, here, here, here, here and here.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.