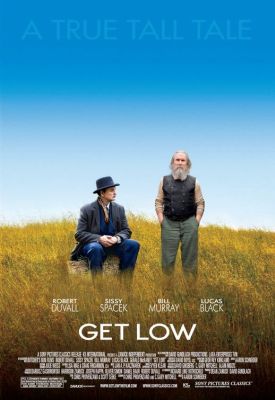

Get Low

Supposedly based on a real incident that took place in Tennessee in the 1930s, Get Low as transformed into a movie turns out to be a showcase for the considerable acting talents of Mr Robert Duvall, but unfortunately not much besides. Even the presence in the movie of those other national treasures, Bill Murray and Sissy Spacek, in engaging character roles is not enough to make up for the lack of narrative energy or moral seriousness. Mr Duvall plays Felix Bush, a curmudgeonly hermit living in the Tennessee woods who decides to give himself a funeral party before he dies. Or not. His inability to make up his mind — party or no party? — does not become any less tedious because we assume that he will eventually go through with it or even because, as it turns out, the point of the party is to give himself an opportunity to confess to people for miles around what he considers to be the shameful episode in his past that induced him to take to the woods in the first place.

Felix’s 40 years of shunning human society — “the first 38 are the hardest,” he observes wryly — are therefore counterbalanced, in a manner of speaking, by the circus, complete with radio coverage, a raffle and a blue-grass band, at which he proposes to confess his darkest and most shameful secret to any idler curious enough to turn up to hear it. “I built my own jail and put myself in it and stayed there for forty God-damned years,” he says at one point. But now, having served what he apparently regards as his time, he says to Mr Murray’s character, Frank Quinn, a raffish undertaker, “I want an end-of-the-line, tell-it-all, get-out-of-jail funeral.” Being raffish, of course, Quinn readily agrees. His assistant, Buddy Robertson (Lucas Black), serves as the voice of conscience, both to him and to Felix — “For everyone like me, there’s one like you, son,” says the latter appreciatively — but he has no problem with the old man’s public confession for the entertainment of a mob.

Does anything about this scenario strike you as implausible? If so, you ain’t heard nothing yet. Naturally, I am forbidden by the critic’s code to reveal the nature of the confession that we know is coming, though a hint of it is given in the film’s opening sequence of a house on fire. But I don’t think anyone will be surprised to learn that what strikes Felix Bush as shameful enough for him to hide his head from public view for 40 years will not strike many others that way. Indeed, the public nature of his confession combines with the nature of the confession itself to reinforce our sense of it rather as something to be proud than ashamed of. His final plea for forgiveness to a bunch of strangers, none of whom he has injured, thus sounds less humble and penitential than it does like an actor’s bid for applause — which will naturally be forthcoming.

Clint Eastwood already made this movie back in 1992, only he called in Unforgiven. It was about an aging hired gun who made something of a public spectacle of his own shame and despair. Or, I should say, his pretense of shame and despair, since real shame and despair don’t run to public spectacles. But even Clint’s William Munny didn’t think of staging his own funeral as public confession. That movie rested on a certain appeal to authenticity — as does Get Low, apart from such verbal anachronisms as “kick your ass”,”I’m outta here” and “I busted my ass for you.” I guess there is something in the self-consciously great actor which such a combination of authenticity and theatricality appeals to, as it obviously does to the many connoisseurs of great acting who promote their enthusiasms in the blogosphere these days. But it doesn’t, at least not by itself, appeal to me.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.