Our Norman Rockwell and Theirs

From The American SpectatorIn an episode of “The Simpsons” titled “Home Away from Homer,” Homer Simpson’s goodie-goodie neighbor Ned Flanders decides to move from Springfield to Humbleton, Pennsylvania — the place where they allegedly make those, you know, adorable figurines — and explains his decision with the typically post-modern comment that “I wish I lived in a place more like the America of yesteryear that only lives in the brains of us Republicans.” Of course, no real-life equivalent of Ned would say such a thing. The supposed non-existence of “the America of yesteryear” is by now a familiar left-wing trope the whole point of which is that people like Ned are pitifully deluded for believing that it existed in reality and not just “in the brains of us Republicans.” Putting such a self-contradiction into his mouth is thus an implicit acknowledgment by the always cutting-edge “Simpsons” writers that the myth of the non-existent American past has itself assumed mythic status by now. How delicious to think that the myth of the myth should henceforth be obliged to don the same quotation-mark epaulettes as the myth itself.

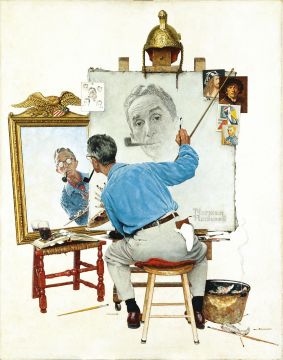

But the news seems to have passed by Mr Blake Gopnik whose review in The Washington Post this past summer of an exhibition of the art of Norman Rockwell at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art slammed the long-dead celebrity “illustrator” (as Rockwell called himself) as the perpetrator of “an art of unending cliché.” Mr Gopnik treats the ur-myth of the wholesome American past as if he has just discovered it instead of something that has now become at least as much a cliché as anything Norman Rockwell ever drew. Indeed, much more so for, in this criticism, Mr Gopnik appears not to know his own critical business. Rockwell was a sentimentalist, if you like, but he didn’t deal in clichés. His images were not in the least hackneyed or familiar ones at the time he produced them. If they have become so since he created them, that is no more his fault than it is Shakespeare’s for writing what have since become so many familiar quotations.

What the critic appears to mean by “cliché” — which, tellingly, he regards as a “sin” — is an affirmative approach to certain bourgeois American values and sentiments that he, in common with most other “progressive”-minded folk, happens not to believe in. While progressive trashings of those values and sentiments are now commonplace, artistic affirmations of them are pretty thin on the ground these days, yet it is the latter and not the former that are still regarded as clichés in the left-wing backwater of the Post’s arts pages. “The reason we so easily ‘recognize ourselves’ in his paintings,” writes Mr Gopnik, wielding the quotes with a po mo flourish, “is because they reflect the standard image we already know. His stories resonate so strongly because they are the stories we’ve told ourselves a thousand times. Those stories couldn’t have been otherwise.”

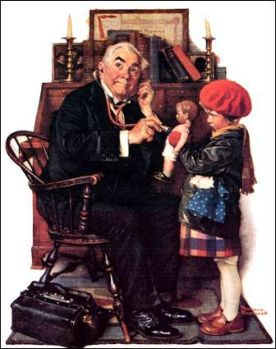

But this is quite obviously the critic’s contribution to Rockwell’s art and nowhere to be found in that art itself. For those who admire him, Norman Rockwell produces the emotional effect that he does precisely because we know the stories could have been otherwise. The kindly old doctor examining the little girl’s doll makes an impression because his condescension (in the old-fashioned sense) to the child is unexpected. When we see the young man returned from the war trying on his civilian clothes in his boyhood bedroom and finding them too small for him, the poignancy of the moment utterly depends on our knowledge that he might easily not have come back at all.

|

Of course this doesn’t make Rockwell’s magazine covers great art, but then he never pretended to be a great artist. Mr Gopnik’s gratuitous attack on this canny, skilled and immensely successful popular illustrator is not only politically motivated, as most criticism (and most art) is nowadays, it has no other point than as a simple-minded reiteration of that tiresome left-wing myth of the right-wing myth of the vanished America. He provides quotations from those he amusingly calls “the experts” (because they share his political views), noting that “literary scholar Richard Halpern has suggested that Rockwell’s vision of America is aware of its own gaps, making his paintings ‘not so much innocent as . . . about the way we manufacture innocence.” Likewise, “the eminent art historian Alan Wallach has dared to see” — I love that absurdly self-congratulatory use of the word “dared” — “Rockwell’s ‘capitalist realism’ as deeply ideological, along the lines of socialist realism.”

This is a mere tautology. To the ideologue, everything is “deeply ideological,” but that has nothing of substance to tell us about Rockwell or what he or his audience thought he was doing. So, too, the idea of manufactured innocence is an oxymoron, striving for paradox, which is really nothing more than a denial that there is any such thing as genuine innocence, in the bourgeois or “capitalist” understanding of the term, just because it is bourgeois. Those who would thus politicize the arts first seek to persuade you that they are already politicized by the purveyors of “clichés” like Rockwell. But the clichés are only counted — and discounted — as such by the prior assumption that they are somehow untrue and politically motivated, or even untrue because they are politically motivated, never mind that the criticism itself is politically motivated. Another name for clichés as Mr Gopnik misuses the term is myths, and Rockwell need be no more be ashamed of being a mythmaker than Mr Gopnik’s “experts” are in propagating the counter-myth.

Rather less so indeed, I should say, since the world as it is looks to me more like Rockwell’s than Blake Gopnik’s. That may be only because I find the bourgeois and “capitalist” myths so much more attractive than their glum and nihilistic competitors, but those competitors obviously have their own attractions, as they have so largely taken over the supposedly popular arts since Rockwell’s time. True, the popular arts are now considerably less popular than they were as audiences have become hooked on “reality” TV, but it is still remarkable that affirmations of even the most obvious things (from the bourgeois point of view), such as patriotism, courage, virtue, self-sacrifice, love, religious faith, service to the community or achievement of any kind are now, ipso facto regarded as politically suspect.

Movies, like other once popular art forms, are inherently affirmatory which is why you have to work very hard to produce the kind of cinematic nihilism that Todd Solondz does. His vile Life During Wartime, which had a brief run this summer before sinking without a trace, makes pedophilia stand, as in his earlier film Happiness (1998) to which it is both sequel and remake, for the evil (including terrorism) that is supposed to blanket the world. So uncompromising is it in its sense of despair about the world it represents that you almost have to admire it for contriving, against all odds, to keep anything positive or hopeful out of it. Could that be the sort of achievement that critics like Blake Gopnik and his “expert” colleagues are looking for in art? Affirmation — affirmation of anything — strikes them as cliché because it hints of the bourgeois revival that would make them irrelevant.

Long before even Happiness, there was a movie called Kids (1995) made by Larry Clark and Harmony Korine. Though not a hit by any standards, it was more popular than either Happiness or Life During Wartime. But, like those movies, it failed as a representation of reality. The problem isn’t that horrible criminal and perverted things we see on the screen never happen. It’s that the film-maker has a responsibility to put them into their proper context — that is to say, the context in which they actually do happen in a world where Norman Rockwell moments, however distasteful to one’s highly developed aesthetic sense, are much more common than pedophilia. In such films, the film-maker turns away from this responsibility to sensationalize — that is, to portray essentially deviant behavior not as deviant but as the norm.

An article by Jonah Weiner in The New York Times attempts to defend Mr Solondz’s nihilistic film-making by quoting Philip Seymour Hoffman, one of the stars of Happiness.

Mr. Hoffman recalled the discomfort he felt on the set playing a character who gruntingly masturbates at one point, phone in hand. “I remember once saying to Todd, ‘People are going to laugh at me.’ Just doing it, there was such a vulnerability that I became really self-conscious. And Todd said, very calming, ‘I think they’re going to feel for you.’ In saying that, he was telling me, ‘I want you to find a way to feel for him.’ He has huge empathy for these characters. He’s not sitting there judging them.”

But maybe that’s the problem. To meet such people on their own miserable terms instead of judging them is to accept the reality of their hellish worlds and so miss out on both the perspective and the hope that judgment would bring.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.