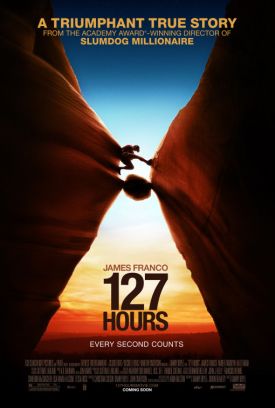

127 Hours

For his latest film, Danny Boyle (Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire) has made the very odd choice of the true-life story of Aron Ralston (James Franco), the young engineer and outdoorsman who, in April, 2003, fell into a rock declivity in Blue John Canyon, Utah, where his arm was trapped by a fallen boulder. After five days of waiting and hoping in vain for help to arrive, he realized that he had to leave the arm behind or he would soon be dead. The result is probably the most fun you could have watching a representation of someone who cuts his own arm off, even though Mr Ralston’s story — told in his memoir, Between a Rock and a Hard Place, on which the film is based — provides too slender a dramatic base to sustain a feature-length film. It’s a great news item or anecdote, of course, but there’s just not enough going on — or so, at any rate, it would seem — to fill more than ninety minutes of screen time.

That’s why it is stuffed with Danny Boyle-type technical wizardry. To break up the monotony, he resorts to much use of split-screen techniques, speeded up motion, hallucinatory dream sequences and, through it all, a lively pop musical sound-track to help make up for the lack of dialogue or movement in the story itself. The first and best of his tricks is that the title doesn’t come until a good quarter of an hour into the picture at the moment when, after its hero’s driving and biking and running and chatting up a couple of pretty fellow-hikers leads him to his fated encounter with the boulder — whereupon we see written on the screen “127 Hours.” The title therefore doubles as a revelation of the ending, or at least of how long it is meant to be until the ending. That, of course, could hardly have been avoided as Mr Ralston’s desperate adventure was widely reported in the press when it happened back in 2003.

Yet even if you concentrate on the substance and ignore the cinematic pyrotechnics, it doesn’t feel like 127 hours. On the contrary, the story as Mr Boyle tells it comes across as a study in how the popular culture, of which Mr Ralston appears to have a typical young adult’s knowledge, equips us to cope with an ordeal like this. His first reaction on realizing that he is unable to free himself, for example, is the teen-speak, “This is insane!” Yet it is also such an engineer-like thing to say! It reminds me of Wyndham Lewis’s provocative contention that nature itself is insane. “The polar bear is insane because he’s obsessed with being a polar bear.” Only man has the self-awareness to escape this insanity of all the rest of the universe. But a man like Mr Ralston whose life and career are built on the assumption of man’s rational mastery of nature must be as flummoxed by the idea of his own helplessness as he is by the prospect of imminent death — at least until he figures out, Sherlock Holmes-style by eliminating all the impossibilities, how not to be helpless anymore.

The echoes of popular argot and of the popular culture in Aron’s mental drama complement the driving rock beat of the soundtrack. He conducts an imaginary self interview on a TV talk show as he films himself with his video camera. “I’m in pretty deep doo doo here,” he confesses, but also “I want to say hi to mom and Brion from work — hey, Brion, I probably won’t be in to work today.” He also recognizes that the TV interview demands self-criticism: “The big f*****g hard hero didn’t tell anyone where he was going? Didn’t tell anyone? Oops!” Another nice touch is when, in the midst of filming himself, he thinks he hears someone and his vain screams for help become helpless screams of frustration. He then watches his own outburst on the video camera and mutters quietly to himself: “Don’t lose it. Do not lose it.”

The two girls, before they parted from him, had invited him to a party, which they told him he could find by looking for the giant, inflatable cartoon dog, Scooby Doo. This object he never actually sees, of course, but his imagination of it haunts his memory, along with remembrances of both sweet and bitter moments with a former girlfriend, dreams of escape and, as his water gives out and he starts to drink his own urine, lurid television advertisements for cold drinks of all kinds. We may ask ourselves, what mental and spiritual resources we would have to fall back on if we found ourselves in such a situation, and it’s rather humiliating, some of us might think, to reflect that they might be nothing but children’s TV shows and hyped-up images from long-discontinued commercials.

At one point, Aron waxes just a bit philosophical, reflecting that “this rock has been waiting for me my entire life” — their encounter, indeed, fated since it fell to earth as a meteorite millions of years ago — but he appears to have no head for religion, nor even any expectation that it might be something relevant, even if rejected, in a situation like his. Or at least not until near the end. Then, after the truly gruesome scenes of his self-maiming and in a state of extreme exhaustion, he finally escapes, but not before he does two things. One is to take a photograph of the scene of his suffering. The other is to whisper “Thank you” to no one in particular. It would have been better in some ways to have ended the movie there, but the final scenes of liberated Aron’s return to life, love and continued outdoors activity does underline and celebrate at least a temporary human victory over the insanity of nature.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.