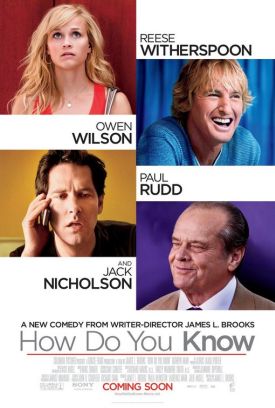

How Do You Know

Tricky! The question posed — provocatively, without a question mark — in the title of James L. Brooks’s How Do You Know, is not answered anywhere in the movie except in the form of a throwaway line, a dirty joke made by a character who doesn’t otherwise appear. How do you know when you’re in love? another character asks — rather foolishly, it seems to me, since if you don’t know you’re not in love. But this nonce character answers: “I’ll tell you how I know. I use a condom with all the other girls.” The joke seems to be at the expense of the promiscuous culture of the professional athlete, which is itself a running joke in the movie, but it also shows an unlovely contempt for the romantic conventions that it is otherwise seeking to exploit. It is also a joke at the expense of the movie itself, which poses a far more interesting question and then refuses to answer it.

We begin with two people who don’t know each other. Lisa (Reese Witherspoon) is an Olympic women’s softball player who, as we know but she doesn’t, is about to be cut from the U.S. team. George (Paul Rudd) is about to open a letter from the U.S. Department of Justice informing him that he is the subject of a federal investigation. While life was still good for both of them, somebody had suggested that these two should go on a blind date. George, showing what a nice guy he is, telephones Lisa to tell her that he is already in a relationship and so can’t make it. Lisa is also dating a pitcher for the Washington Nationals named Matty (Owen Wilson) whose idea of post-coital charm after their first, casual encounter is to say to her: “Female jocks are amazing!” — and then, by offering her a sweatshirt from a large store of them he keeps for such occasions, shows how he knows whereof he speaks.

This is not (quite) enough to put Lisa off — which is more amazing even than female jocks — but she does consider herself at liberty to accept a subsequent proposal for a dinner date when George’s girlfriend, on the news of his looming indictment, dumps him by saying that “we are not well-matched for this interval in your life.” The two go on their date but, as it is overshadowed by George’s personal misfortune, no sparks fly. Instead, Lisa, prior to the receipt of her own bad news, cheers George up by proposing that they dine in silence. This is not the only puzzling thing about this movie. Why should not-talking have a therapeutic effect? Of course, we know from the beginning that these two are destined to be together, so pretty much everything has a therapeutic effect. As a result, too, when they do begin talking, they are like monkeys picking lice off each other, as their courtship consists of mutual therapeutic grooming. Sample: “Deny a voice to the thing that’s feeling upset.”

Yeah, that will work.

Since the question of “how do you know” is of no real interest to anyone except (briefly) Matty, the film instead turns on that more interesting question I mentioned earlier. It is this. Should nice-guy George go to jail for his business tycoon dad (Jack Nicholson), the kind of guy who, if there is any such kind of guy, says that “cynicism is sanity”? If he doesn’t, dad himself will himself go to jail for life. For, not surprisingly, George is completely innocent of any wrong-doing, but his dad is not. He, George, can save him by taking the blame for the company’s bribing of Middle East middle-men. Do people really go to jail for that, let alone for life? Perhaps they do. But that a father would ask his only son to spend three years in the slammer to save his own skin, or actually connive to bring it about, is not the least of the film’s implausibilities. I think you’re supposed to laugh when dad compares his anguish on asking his son to go to jail for him with “the side effects I got from Lipitor,” but instead you just wonder at the kind of person who could think that funny.

It’s just one of several things about this movie that are a bit off, as the British would say, and that are constantly pulling against its attempts at humor — which, apart from a few one-liners, are mostly pretty feeble anyway. Also, though I like Paul Rudd and am sure he is as nice a guy as George himself, he’s simply not leading man material. I’ve never been that enamored of Reese Witherspoon since Election either, and both the Owen Wilson and Jack Nicholson characters tip over, as Owen Wilson and Jack Nicholson characters so often do, into caricature. The seriousness of the moral dilemma in which George finds himself sorts ill with both the attempted comedy and his lightweight persona on the screen, and the way in which Mr Brooks contrives to get him out of it simply dodges the problem anyway without requiring him to take any kind of moral stand. George’s last inspirational thought to Lisa is that “we are all just one small adjustment away from making our lives work.” I don’t think that can be true of our lives, but it’s certainly not true of Mr Brooks’s movie.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.