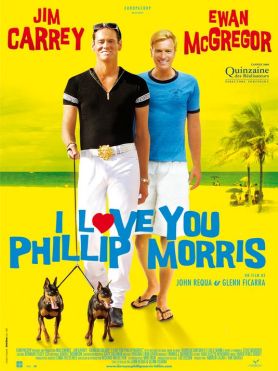

I Love You Phillip Morris

I Love You, Phillip Morris, a collaborative directorial and writing effort by Glenn Ficarra and John Requa based on a book by Steve McVicker, obviously made a lot of American distributors nervous. Though a thoroughly American film that was a big hit at Sundance nearly two years ago, it was released first in Europe way last spring. My guess is that its portrayal of its gay hero, a real life con-man named Steven Russell, played here by Jim Carrey in his best role since that of Joel Barish in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, didn’t fit comfortably enough into the politically correct gay stereotypes — or the politically incorrect ones either, for that matter — for American audiences to know quite what to make of it. That must be why the film is prefaced with a printed notice that “This really happened” — followed, a few seconds later, by another: “It really did.” Well, maybe not this, precisely, but something near enough to it that you would be equally astonished at the outrage to your pre-conceived notions about gay people.

That this is a story about being gay, first and foremost, I don’t think there can be any doubt, and it is in some ways a typical gay narrative, told in flashback and with Mr Carrey’s voiceover from what purports to be his character’s deathbed. Raised by conservative adoptive parents in Virginia Beach, Virginia, Mr Russell is seen growing up to be a policeman, a Christian evangelical of some description and a dutiful husband and father, a point underlined when we see him and his wife, Debbie (Leslie Mann) praying together — though the words are Debbie’s and include effusive thanks to God for such an ideal husband — at the foot of their bed before retiring for the night and then engaging in a very unerotic act of sexual intercourse.

Steve interrupts the proceedings by telling Debbie of how he is using the entré given him by his badge to search for his birth mother, a woman named Barbara Bascombe (Marylouise Burke) who sold him to his adoptive parents in a parking lot for a paper bag full of cash. In a subsequent scene, his search has an unhappy but darkly funny conclusion as he calls out to this long lost mother, who is celebrating the birthday of one of his two long-lost brothers behind a firmly-locked door: “I was the middle child! What was wrong with me?” Soon afterwards, we again see him in a sex act in which his partner is suddenly revealed to be a man. “Oh, did I forget to say I’m gay?” he says in voiceover.

Well, it’s the old story. He had tried to conform to society’s norms but eventually got sick of “living a lie.” After a car accident in which he is badly injured, we see him being loaded all covered in blood into the back of an ambulance and announcing to the paramedics: “I’m going to be a fag! A big fag!” You couldn’t say that this is represented as a pure “lifestyle” choice, of course, as Steve dutifully insists that in choosing to be a big fag he is choosing to be “the real me.” But it is also the case that the idea of “the real me” swiftly becomes problematical in other ways. Once he has left his wife and daughter and taken up with a lover named Jimmy (Rodrigo Santoro), he adds: “Nobody tells you this, but being gay is really expensive” — and so begins his criminal career.

Debbie, who remains on good terms with Steven after they have split up, is meant to be seen as an air-head, of course, and nowhere more so than when she inquires of one of the detectives during her ex-husband’s first arrest for credit card fraud, “Is the gay thing and stealing, are they something that goes together?” Yet of course the film cannot avoid showing us how “the gay thing” and stealing do go together in Steven’s case — at least insofar as both involve his assuming alternative identities in order for him to get what he wants. At some level, the film at least hints at an assimilation of the “gay” persona with that of his con-man disguises as different iterations of the same American story of self-invention and re-invention.

In prison, Steven meets the eponymous Phillip Morris (Ewan McGregor), the love of his life, and their courtship is both touching and funny. I particularly liked their slow-dancing together to Johnny Mathis singing “Chances Are” after lights out as their butch neighbor fights off a whole shift of prison guards to keep the music on because he has been paid to do so. As he is being beaten up off-screen, he keeps repeating as Johnny keeps singing, “My word is my bond!” But this practised liar and con-man lies to and cons Phillip as well — perhaps because there is simply no obvious place to stop once you accept, as we are encouraged to accept here, that people ought to have a virtually limitless right of self-invention. “How can I love you when I don’t even know who you are?” says Phillip reproachfully when he becomes another of Steven’s victims.

But Steven doesn’t know who he is either, and the point of the film is that this hardly seems to matter. Being “who I am” — as the gays who have now succeeded in ending “Don’t ask, don’t tell” in the name of being it invariably say — turns out not to be the real issue after all. It’s not being who I am but who I want to be. The problem with the film, which is so enjoyable in so many ways, is that it doesn’t have any problem with this. It is happy to be as indulgent with Steven’s criminal career as it is with his homosexuality — which means that, having brought up the matter of making moral choices (or choices that are inevitably fraught with moral meaning) it then refuses to take them seriously.

Instead, at the end, it takes a gratuitous swipe at George W. Bush, who happened to be the Governor of Texas at the time that the real life Steven Russell was sent to prison there for 144 years. Unlike Brokeback Mountain which applies the romantic notion of fatal and tragic love to a gay relationship by treating its gayness as being merely adventitious, I Love You Phillip Morris is more optimistic and more American in its apparent commitment to the view that we choose our own fate and that being gay is, therefore, also something to be chosen and not merely to be endured. Then at the end to turn around suddenly and make Steven a victim of wicked Republican “law-and-order” types or perhaps even, God help us, “the system” is a bit of vulgar sophism, a way of easy escape from the real problems it raises, that is unworthy of a movie which otherwise seems to aspire to moral seriousness about the choices people make.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.