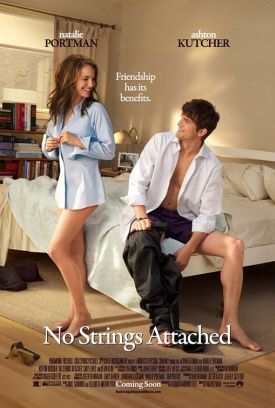

No Strings Attached

One line which people are likely to remember from the otherwise pretty forgettable No Strings Attached, directed by Ivan Reitman from a screenplay by Elizabeth Meriwether, is spoken by the disgruntled roommate of Emma (Natalie Portman) as the latter is engaged in one of her frequent bouts of noisy copulation with Adam (Ashton Kutcher), an old acquaintance. Adam, unsurprisingly, has readily agreed to Emma’s proposal that they should remain “sex friends” only, avoiding all emotional entanglements, but of course we know from the beginning how this is going to work out for them — as you, too, will know it even without having seen the movie. But this takes nothing away from the comic snap of the roommate’s line, which is delivered in the form of a complaint: “I can’t focus on my porn with all this sex going on around me!”

What may take away from it among the more thoughtful sort of movie-goers is this: in our culture today it is becoming increasingly difficult to tell the difference between porn and “sex,” which is just one of the difficulties under which this movie labors. Shortly after Adam and Emma have sealed their deal for no-strings-attached sex, Adam notices a stranger walking his dog who has just seen the two of them parting. For some reason, Adam thinks he needs to explain their relationship to the dog-walker. “We’re sex friends,” he says. “Friends who have sex.”

“That’s not possible,” says the man, and walks out of the picture.

Ha ha. Wasn’t there a “Seinfeld” episode about that? The stranger, in giving voice to the current wisdom on such a fascinating subject is merely telling us that this is that kind of movie ( the fall-in-love kind) and not, however much it may seem so, this kind of movie (the friends-with-benefits kind). Surprise! In other words, it turns out the way every friends-with-benefits movie since the late Peter Yates’s John and Mary (1969) turns out. Yet we know that we are still dealing with recognized categories of feeling that come under the heading of what in the sixties we used to call “experimentation” — as in, “He experimented with drugs.” To my admittedly jaded ear, the amount of comedy to be milked from watching this supposedly new and unconventional arrangement as it concludes in the warm embrace of an even older convention is pretty limited.

But “sex” has its conventions just as love does, and its own ideology based on them. The word “sex” itself, in the sense that the roommate uses it, is of relatively recent vintage. “Having sex” to our great-grandparents was something that everyone did at birth, since it referred to a taxonomic classification characteristic of most living things above the microscopic level and not the act by which they reproduced themselves. The newer meaning of the word — “now the most common general sense” — dates to H.G. Wells’s Love & Mr. Lewisham of 1900, according to the O.E.D. and was given a new impetus by D.H. Lawrence a few years later, but the word came into use gradually as it gradually became possible to speak of what would formerly have been considered the obscene notion of sex divorced from its then-normal social context of marriage.

This stripping away of context in the form of long-established and painstakingly constructed social and moral customs was a necessary prelude, then, to both “sex” and porn — which, though the thing itself had been around for centuries, had been literally unspeakable, at least in English, since the word “pornography” only antedates the new sense of “sex” by about half a century. Now it has assumed a central place in our culture. A week or so after No Strings Attached was released, New York magazine published a cover story by Davy Rothbart on “Porn and the Vanishing Male Libido” which suggested that porn was actually replacing sex for a lot of men who enjoy the luxury of being able to choose between them. On the news-stands at the same time was Natasha Vargas-Cooper’s cover of the Atlantic with its startling revelation that the latest fashions in internet porn can be summed up as “amateur hour” — so much so, indeed, that professionally produced pornography has to emulate the production values associated with cell-phone cameras in order to remain salable to connoisseurs in search of authentic-looking images of “sex.” That porn has gone mainstream is yesterday’s news. Today porn and mainstream sex are two aspects of the same phenomenon.

Perhaps that’s why movies like No Strings Attached are drawn to reinvent the long lost social context of sex, or something that can stand in for it. Not surprisingly, this reinvention is conceived along feminist lines. It is the young woman in this case who has made the necessary separation between the emotional and the physical which used to be thought characteristic of men. She is the one insisting on keeping the relationship strictly physical, while the young man (necessarily) finds himself “falling in love” with her and so unable to keep the relationship going without an emotional connection. The result may be the same, but it’s important that they get to it by a different route from that prescribed by custom, both in life and the movies — a route that finds its way around the “stereotypes” of male and female behavior. I think this is meant to make it seem fresh and original.

The plot of one of the funniest episodes of HBO’s very funny series, “Flight of the Conchords” has its two clueless Kiwis picking up a couple of girls and Bret, the better looking of the two, adopting the female role of reluctant seductee vis vis Lisa (Eliza Coupe), who accordingly takes on that of the sexually predatory male. Naturally, that means that she swiftly loses interest once she has had her wicked way with him, and he is devastated to overhear her bragging to her girlfriends about how easy he was. As with men in drag, the outlandishness of such role-reversals is necessary to the humor because it reminds us of the unnaturalness, the preposterousness of what we are seeing. No Strings, by contrast, depends on making the unnaturalness of Emma’s divorce of sex from feeling look natural. Why shouldn’t she behave just like a man? Are you saying there’s anything wrong with that?

Well, yes, as a matter of fact. There’s a lot wrong with it. It’s wrong when men do it too, but the fact that men in real life do it so much more often than women is a truth which will not be ignored, however much we may pretend for ideological reasons that the sexes differ in no significant ways. The cultural legitimization of both “sex” and “porn” happened in the 1960s and has ever since made the characteristic masculine moral failing the default position for both sexes — as if any protest on behalf of the virtues once thought characteristic of womankind, modesty and sexual continence, were tantamount to a return to the bad old days when women are now thought to have been virtually enslaved to men. Thus in No Strings, when Emma’s friend Shira (Mindy Kaling) says, “We’re sluts, Emma! We’re dirty, dirty sluts!” it is with a note of triumph in her voice, as much as to say: We’re modern women now, no longer hidebound by the oppressive conventions of the past. Breaking with convention has become more important for her than the relationships the break prevents her from forming.

Yet No Strings Attached is also a movie about generational relationships and differences and this almost but not quite adds another and more interesting dimension to the film. Both of the main characters are embarrassed by their parents, who are children of the sixties and still (apparently) as sexually adventurous as they were in the days of experimentation. Adam’s father Alvin (Kevin Kline) is “dating” — curious how the euphemism survives the liberation — his, Adam’s, ex-girlfriend Vanessa (Ophelia Lovibond), while Emma’s mother Sandra (Talia Balsam) is dating a drugged-out hippie called “Bones” (Brian H. Dierker) who doesn’t speak but, says mom, gives her great sex: “That’s why they call him Bones.”

As with the comedy of a pretended truancy from a convention that has been dead for 40 years, so the comedy of too-much-information here is only a feint. The embarrassment leads nowhere, just as it does in the allusion to menstruation in the punning title and the song, “Bleeding Love” by Leona Lewis, that becomes the movie’s theme song. In the end, the embarrassed children only learn that their lusty parental units were right all along and that, as Alvin tells Adam, “the worst thing you can do in life is to say no to love.” Of course, it sounds better that way than it does if you substitute — which is what Alvin really intends — “sex” for “love.” But that’s all part of the movie’s more general pretense that there is an easy compromise or modus vivendi between the ethos of the sexual revolution and traditional romantic comedy. I, for one, remain unpersuaded.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.