True Grit

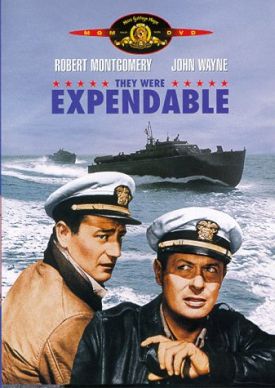

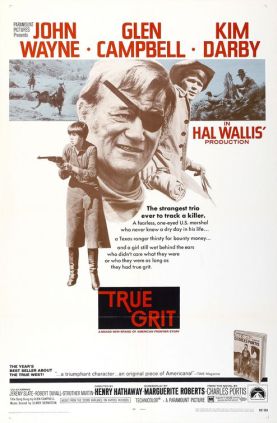

One scene from the 1969 version of True Grit, directed by the journeyman Henry Hathaway, that is interestingly altered in the new remake by the Brothers Coen comes when John Wayne as federal marshal Reuben, “Rooster,” Cogburn — who is played in the remake by Jeff Bridges — is giving his employer and protégé, Mattie Ross (Kim Darby), a résumé of his life since his disreputable service with Quantrill’s Raiders in the Civil War. He tells her without any sense of shame of having robbed both a Federal payroll and a bank in New Mexico. The story is somewhat abbreviated from the version given in the novel but is substantially the same, as is Rooster’s denial that what he had done in the two cases was the same as theft. “I needed a road stake and there it was,” he says. “I never robbed no citizen, taken a man’s watch.”

“It’s all stealing,” Mattie replies.

“That’s the position them New Mexicans took!” he says with just the right amount of astonishment in his voice, as if it were quite the coincidence for him to have found someone else with such eccentric views. “I had to flee for my life!” And he then proceeds to tell the story of his escape from the New Mexican posse.

In the Coen version, the story of the escape is really the point of the exchange and comes first. Mattie (Hailee Steinfeld) then asks, “Why were they pursuing you?” and he tells her “I robbed a high-interest bank. You can’t rob a thief can you?” This is part of the fuller account in the novel, but in its context there does not suggest that Rooster saw himself as some kind of Robin Hood. More importantly, the Coens’ leaving out the business of the “road stake” doesn’t allow the sense of the character’s peculiar sense of honor to come across. Mr Bridges’s reply to Mattie’s “It’s all stealing” sounds like a one-liner, delivered with a wink, and not like the reverberation of a whole different moral universe. In another scene that the Coens omit entirely, Wayne drills a rat with his six-gun, explaining to Mattie as he does so: “You can’t serve papers on a rat; you’ve got to kill him or let him be.” So much for legal niceties! No wonder Richard Nixon is said to have written Wayne a fan letter, even though the screenplay was by blacklisted Communist Marguerite Roberts.

|

Most people in 1969 would have understood that Rooster is a man of classically heroic stature, a man who stands outside and above the law. “If the President does it, it’s not illegal,” as Nixon was later to put it to David Frost. Wayne’s character, Tom Doniphon, in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) is there to make much the same point. Later, in yet another scene that the Coens do not repeat, Rooster has to rob some people at gunpoint of their horses and buckboard in order to get Mattie to an Indian doctor in time to save her life after she has been bitten by a snake. The suggestion is — as it also is in Liberty Valance — that necessity does sometimes justify a disregard for the law.

This inconvenient truth is meant to contrast with the quaint moralism of the revenge-seeking Mattie, who has hired Rooster to bring her father’s killer in dead or alive. In the Coens’ version of Mattie, there is still a touch of her Old Testament grandeur in demanding a strict moral accounting for that death — which (unlike Hathaway) they do not represent. But it is only a touch. Miss Steinfeld was actually younger when she made the movie than her 14-year-old original in Charles Portis’s novel. But the more salient contrast with the Mattie of Miss Darby (who was 20 at the time), is that she is less religious, less moralistic and more interested in the law, of which she has a considerable knowledge, acquired we don’t know how. Miss Darby’s Mattie is a less interesting and less attractive person, but she has the strict sense moral rectitude which seems to me at least to ring truer of a frontier lass of the 1880s. Her successor has something of that newer movie favorite, the child prodigy about her.

The new film isn’t really interested in what I regard as the serious question of the moral ambiguity of the heroic so much as it is in the less interesting and more general moral chaos of the world that was also characteristic of the brothers’ view of things in such recent films as No Country for Old Men and A Serious Man. In one way, however, this makes for a better picture — as does the fact that, like all its authors’ movies, it is a much more highly crafted piece of cinematic workmanship. It means that it is more focused on the heroism of its heroes — who include Matt Damon in the role of the Texas Ranger La Boeuf, played by an absurdly miscast Glen Campbell in the earlier version — and less on its moral significance. The season of their quest to capture and bring to justice the murderer, Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin), is changed from summer to winter in order to stress the hardships they must endure, the landscape is less picturesque and more authentic and the violence, including the hanging at Ft. Smith which occurs near the beginning of both films, is more graphic.

Mr Bridges is inevitably a less-imposing screen presence than the Duke, but then who isn’t? And the fact that he brings the heroic more down-to-earth is in keeping with the darkness of the rest of the film’s vision. I also like that they have kept so much of Mr Portis’s old-timey language in the dialogue — what the New York Times reviewer called its “twisty, funny sentences.” The smack of authenticity is doubtless an illusion, but it is no less an effective one for that, and an unbiased viewer will find in the film itself no trace of the reviewer’s mistaken and ideologically motivated attribution to it of an obsession with what she calls, remarkably, “that old-time American religion of vengeance.”

Its other negative virtue is that the Coens manage to resist the temptation — which they did not resist in the two films mentioned above — to make too much of a point of the moral indifference of the universe to our ideas of justice. If you doubt this, just look at their use of the hymn tune, “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” as a musical leitmotif. That this does not immediately strike one as being ironic strikes me as a triumph of modesty and restraint over the usual smirking Coenism.

Leaning, leaning, safe and secure from all alarms;

Leaning, leaning, leaning on the everlasting arms. . .

What have I to dread, what have I to fear,

Leaning on the everlasting arms?

I have blessed peace with my Lord so near,

Leaning on the everlasting arms.

Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter (1955), another film about children endangered by an evil man, used the same trick except that its irony was at the expense of the evil man, a faux preacher played by Robert Mitchum who sings it as part of his pose of religiosity. By piping it in over the soundtrack and making no obvious connection to the drama on-screen (except for a brief and otherwise irrelevant scene of hymn-singing at the hanging), the new movie merely hints at the consolations others have found in the idea of a just but merciful God without — quite — sneering at them. Mattie is still allowed the frontier wisdom that “Nothing is free but the grace of God” even if the film-makers themselves are agnostic about this. And she does, after all, get her man — though the price she pays for the justice she seeks is enormous and apparently includes her never getting a man in the sense that young ladies were once expected to do.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, of course! But by bringing in the grown-up Mattie as old maid (Elizabeth Marvel) at the movie’s end, the Coens restore Mr Portis’s framing device, whose omission from the John Wayne version was part of what made that movie at once simpler, sunnier and more satisfying than the remake. Such virtues are rather thought to be vices these days, however, and I expect that most people will prefer the newer, more up-to-date True Grit. Undoubtedly, it’s more to our contemporary taste. Yet I think I have to go with the 1969 version, even in spite of Glen Campbell’s warbling of its brain-dead theme song, “One Day, Little Girl” (music by Elmer Bernstein, lyrics by Don Black) with its glib assurance that

Though summer seems far away

You’ll find the sun some day

The Coens may have a juster appreciation of the difficulties we all have in coming by any sense of the moral order in the universe, but the earlier film reminds us that without one there’s not much point to even the most craftsmanlike representation of its heroes’ sufferings.

This article has been modified since its original posting and a mistaken account of the Coen’s version in the first four paragraphs has been corrected.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.