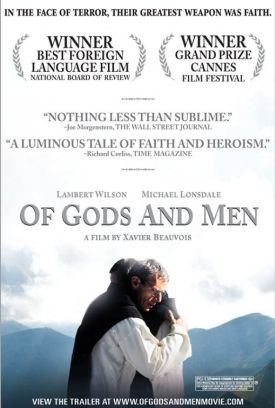

Of Gods and Men (Des Hommes et des Dieux)

It’s still only March, but I don’t hope to see a better movie this year than Xavier Beauvois’s Of Gods and Men (Des hommes et des dieux), winner of the Grand — meaning second — Prize at last year’s Cannes Festival. It tells the true story of the Trappist Monks of Notre-Dame de l’Atlas in Tibhirine, Algeria, whose little monastery, a forlorn relic of the French imperial presence in that country, was invaded and the monks kidnaped and later murdered by Islamicist guerrillas in 1996. M. Beauvois does not sensationalize their deaths, however, and he appears to have little interest in the political conflicts within Algeria that led to them. This is no accident. The historical Brother Christian (Lambert Wilson), the prior of the Tibhirine monastic community, belonged to a French military family and had himself served during the Algerian war. Much might have been made of the fact, if the film had had a political or historical or, indeed, a psychological point to make instead of a religious one. As it is, however, its focus on the piety, the goodness, the fellowship and the courage of the monks is much more interesting and unusual and in my opinion could not but have suffered from the introduction of a political subtext.

At one point, it’s true, a secular Algerian official tells Brother Christian that he blames the insurgency on French colonialism (“that organized plunder”), which had ended more than 30 years earlier, but this comes across as self-serving, a mere reflex on the part of one of many in post-colonial Africa who still take comfort from having someone else, even someone else long ago, to blame for their failures. The villagers who depend on the monastery for medical care and material assistance are as frightened of the government and the army as they are of the guerrillas, and they desperately want the monks to stay among them. “But without protection?” asks one of them.

“You are the protection,” says an Arab woman.

“We are like birds on a branch,” says another monk — birds who don’t know if they will fly away or stay on the branch.

The same woman replies: “We are the birds; you are the branch. If you leave, we lose our footing.”

Accordingly, the one guerrilla fighter to whom the film introduces us, Ali Fayattia (Farid Larbi) is a complex and even somewhat sympathetic character. We see him commit at least one brutal murder — this is the only graphically disturbing scene in the film — but at the same time he respects the monks and recognizes the indispensable role they play in the lives of the villagers. He even apologizes for disturbing the monastery’s Christmas eve devotions when he and his men make a nocturnal visit in search of medicine. He had been unaware of the significance of the date to them, he says. It seems that Fayattia is protecting the monks from some of his more brutal and, perhaps, fanatical confreres who are only free to engage in the final terrorist outrage once he is removed from the scene. As in real life, there is no good political outcome of the war which rages around the monks, but there is at least an imaginable human outcome implied by the mutual tolerance issuing from the otherwise terrifying confrontation of Ali Fayattia and Brother Christian.

|

The story of the Tibhirine monks themselves, however, is the real heart of the picture, and it is told as an extended allusion to the passion of Jesus Christ, including a healing ministry, the odd miracle, a gratuitous political intervention, a moment of doubt and a last supper — including bread and wine (and a recording of Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake”) — before the inevitable martyrdom. Apart from Brother Christian, the most memorable of the little community is its medic, Brother Luc (Michael Lonsdale) — reminiscent of Luke the physician, supposed author of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of the Acts of the Apostles — who has worn himself out in the selfless service of the villagers of Tibhirine. “I’m not afraid of death; I’m a free man,” he tells Brother Christian. But it is the latter whose own fear, answering that of the less saintly brothers, inspires him with the sympathy needed to encourage them when they have to make the decision to remain where there is so much danger and so much to be done or to go back to a France that most of them left decades ago.

This story is punctuated with scenes of the monks’ devotions, their chants and prayers and readings that provide a counterpoint to their worldly chores and fears. When they chant that “God charges no soul save to its capacity”or one of their readings throws up a sentence like “Weakness is not a virtue but a fundamental reality” there is an instant resonance that helps us as well as them to an understanding that their lives in this place and this time are continuous with their deaths. “Dying here, now, does it serve any purpose?” one of the monks asks Brother Christian.

“Remember,” he replies: “you have already given your life.”

I have written that there is no overt political purpose to the picture, and that I think it is all the better for that, but there are certainly political implications, if only of a negative sort. Those who put their trust in political solutions to social problems and political remedies for human misfortunes will find naught for their comfort here. Once having decided to stay, the atmosphere of constant fearfulness amidst the daily round of work and prayer is made palpable and gives point as well as almost unbearable pathos to the prayer of the doubter, Brother Christophe (Olivier Rabourdin): “Help me! Don’t abandon me, please!” It is one measure of Xavier Beauvois’s very considerable accomplishment in Of Gods and Men that it is possible for the faithful to believe Brother Christophe’s prayer was answered.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.