Preening to the Converted

From The American SpectatorJoyce DiDonato

Not long ago I went to a recital at the Kennedy Center in Washington by the mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato, a lovely woman with a lovely voice whose renderings of little-known pieces by Rossini and the French composers Cécile Chaminade and Reynaldo Hahn were revelatory. The near-capacity crowd in the KenCen’s 2454-seat concert hall were wild about her and called her back at the end of the performance for several encores. As artists sometimes do, she took the occasion to chat with the audience, wondering if perchance President Obama might be present (he wasn’t) and inviting the audience to share her joy in the recent triumph of Egyptian idealism in Tahrir Square, Cairo. She mentioned that she had kept up with events on her musical tour of American cities by watching TV news on CNN and MSNBC — but “not much on Fox.” This got a roar of approval from the audience as did one or two other things she said indicating her liberal sympathies and disobliging opinions of conservatives and conservatism.

About this, the reviewer for The Washington Post had this to say: “In a field that so often seems to exist in a rarefied atmosphere away from the world, she has the directness of a pop musician — not to try to impose any kind of political message on a program, but just to remind everyone of the world of which classical music is a part.” And, annoying though I had found Miss DiDonato’s remarks to be, I could see the reviewer’s point. For there’s no denying that “the world of which classical music is a part” — not to mention the larger world of artists and intellectuals of which it is itself a part — is in its sympathies and presuppositions overwhelmingly liberal. Or perhaps more precisely, anti-conservative. That is why this adorable songbird, born in Prairie Village, Kansas and an alumna of Wichita State University, was able to assume that political views which might have come from The New York Times would be gratifying even to (especially to!) an audience in Washington where, as the whole world knows, a horde of new Republican office-holders had recently arrived.

It’s no news that nearly all artists, like much of their art, are now overwhelmingly of a leftish persuasion. That is why classical music and “progressive” news organizations like National Public Radio go so naturally together — and why, also, the newly arrived Republicans in Washington have put Public Broadcasting on the chopping block. The broadcasters are worried, too, and have deployed, as they always do, “the Muppet lobby” to try to hang on to their taxpayer bucks. My local PBS and NPR outlets have been running frequent announcements setting out the damage the GOP proposals to defund them would do — not to them but to me. “These cuts will have a devastating effect on WETA and the television and radio programs that you and your family rely on,” the announcement goes, detailing programs “like ‘Masterpiece’, ‘Mystery’, ‘Nova’ and ‘the PBS NewsHour.’ Do your elected officials know how you feel about funding for Public Broadcasting? Call your representatives in Congress today and let them know where you stand.”

|

This statement must have been cleared by the station’s undoubtedly very competent legal counsel, for at no point does it express a political point of view or advocate a particular political action, which would not be allowed. It merely urges viewers to make their views known. But of course the folks at WETA can be pretty confident about what those views are likely to be, and that they coincide with their own on this as on other matters. Like Miss DiDonato, public broadcasters know their audience and can assume a community of interest encompassing political as well as social, artistic and intellectual matters.

They know, as Sam Guzman of The Christian Science Monitor recently wrote, that “conservatives have abandoned the arts.” It may be, he admits, that “conservatives are better arguers, but liberals are better artists. I am not specifically referring to either fine art (if there remains such a thing) or popular art. It doesn’t matter: Liberals control both. They have MTV, but they also have the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. They have Rolling Stone, but they also have The New Yorker. They have Hollywood, but they also have Cannes.” So far, I’m afraid he’s right, but I think his explanation for this sad state of affairs is mistaken. “Liberals,” he claims, “understand that rooted deep in the human soul is a love of beauty, a fascination with story, and an intangible sensitivity to the singing of songs. That’s why liberals have sought to control not only the Senate, but the symphony, the storybook, and the silver screen. Reason is a blunt instrument. It can smash with all the force of a hammer, but it is art that subtly serenades and seduces.”

Fair enough, you may think, but what has the love of beauty or a fascination with story got to do with most of the art, fine or popular, now being produced? His example of the art that subtly serenades and seduces is James Cameron’s dreadful blue 3-D nightmare, Avatar which, though he correctly identifies it as left-wing environmentalist propaganda, he finds “persuasive,” at least to the illiterates — his word, though he doesn’t mean it in a bad way — who flocked to the movie in their millions. I doubt how persuasive this movie really was, even to the relatively limited and mostly pre-voting-age audience to which it primarily appealed. The point is not that the other side is winning through the power of its art. Actually, in the postmodern era art has become more political while becoming less persuasive — partly for the same reason that Miss DiDonato knew she could badmouth Fox and be applauded for it: because the artists know their audience already shares their opinions. Art has pretty much renounced any pretension to power along with its pretension to verisimilitude, and its new fantasy-land is cut off not only from reality but from those of us, including most conservatives, who have refused to join them in flight from it.

No, the real point is that we have no contemporary art of our own but have to share that of the other side for the sake of what poor nourishment we can derive from it. At any rate, that’s what generally strikes me about post-1960s movies that are said to be “conservative,” like the Mel Gibson vehicles Braveheart (another movie with blue people in it), The Patriot or The Passion of the Christ, which are in my view hardly to be distinguished from the brain-dead claptrap of Avatar — as I like to think conservatives would know if they hadn’t given up on the movies years ago and so got out of the habit of critical thinking about them. What pathetic crumbs from Hollywood’s table now satisfy us! If we conservatives can’t do any better than that, maybe we’re better off without any art of our own.

|

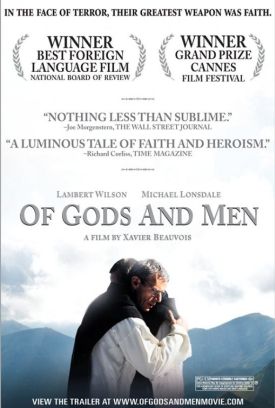

But we can do better — with the stipulation that, where we do, it will be not as conservatives but as those in touch (as liberals so seldom are anymore) with a world outside and above politics. The best conservative movie I’ve seen for a long time was made by a young Frenchman, Xavier Beauvois, who identifies himself as a socialist and doubtless would repudiate with vigor any imputation to him of political conservatism. The movie is Of Gods and Men (Des hommes et des dieux), and it tells the story of the Cistercian monks of Tibhirine in Algeria who were kidnapped and murdered by Islamicist guerrillas in 1996. Such a story obviously has an enormous potentiality for political interpretation, but apart from a mention by an Algerian official — a self-discrediting source, as the movie itself shows — that he blames French colonialism (which ended in 1962) for the insurgency M. Beauvois (Le Petit Lieutenant) is not interested in things political. Instead, he gives us a portrait of piety and martrydom the likes of which has not been seen in an English-speaking movie, so far as I know, for a generation.

Interestingly, the reviewer for The New York Times, though he liked the movie as much as I did, felt the need to reassure his own liberal audience that the movie was not really about Christianity but “rather an almost fanatical humanism” — which is a contradiction in terms if I ever saw one. He tries to find in it some kind of statement about “the sins of colonialism,” presumably to justify his own approval of what he has seen. But don’t be fooled. There is no such thing, nor is it true to say that “the theme may be piety, but Mr. Beauvois and his cast do not address it piously.” The community of interest of those who read the arts pages of The New York Times, which must overlap to a large extent that of the audience in the Kennedy Center the other night, may be reliably anti-conservative, but the art that, for want of anything better, they worship, can never be so if it is to remain art at all.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.