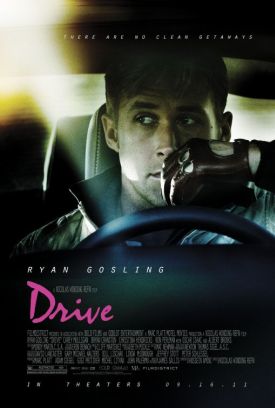

Drive

Strange, isn’t it, that the more (officially) pacifistic and non-violent our society becomes, the more incendiary and warlike our political rhetoric is? I wonder if there could be any connection with the movies’ penchant for seeking out new but politically correct ways to idolize men of violence? The seemingly endless string of celluloid superheroes is one example. They earn their right to murder and mayhem through their inhumanity. They belong to a master race of their own and live in a world which allows them to operate according to different rules and with a different morality from the rest of us. Vigilante justice in real life, administered by any mere mortal like ourselves, would be in the highest degree unacceptable, but we don’t call it that when superheroes do it. Of course the price we pay for our superheroes is having to live in toon-town with them to the extent that we take them to any degree seriously.

But there are other ways to revive the old sense of honor attaching to killers. The precursor of the cartoon hero in the movies was the cool hero played by the Steve McQueens and the Clint Eastwoods (before the real-life Clint turned into a morally earnest director) of old and their later imitators: men who earned their right to violent methods by being outsiders, lone men of integrity standing up to a corrupt system. Their violence is sanitized partly by being stylized, like that of the cartoon hero, and partly because they are seen as existing in a state of Hobbesian nature where civilized alternatives to violence are either corrupt or not available. The trope of the lone honest man fighting a corrupt system has become rather a cliché, however, so cool heroes mostly go heavy on the stylization — which means that there is a certain sameness to them.

The latest example of the breed is on display in Drive by the Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn. The hero, played by Ryan Gosling, resembles the movie itself in being reduced to the verb describing what he does: drive. He is also another “man with no name” — which is a time-tested way of stressing his individuality and his detachment from normal social convention. The driver works in an L.A. garage or as a movie stunt-man by day and as a getaway driver for ambitious burglars by night. Ahead of the opening credits, we see him executing a perfect evasion of a police pursuit by car and helicopter in almost complete silence — silence broken only by the sounds of the street and the crackle of the police radio which alerts him in advance to the next move of his pursuers. When we hear the police say that they have “lost visual” we are alerted to the director’s own technique of getting and losing visual on his hero in order to evoke the romance of the city at night and the paradoxical loneliness of its ghost-like familiar spirit.

He, the driver, you will understand, is only a criminal by necessity — even though the necessity, like other narrative details, is not specified. It’s enough that we see and hear him greet a prospective employer with a lucrative “job” in the works by saying: “How about this? You shut your mouth or I will kick your teeth down your throat and shut it for you.” He really does prefer silence to speech, it seems, but that’s pretty typical of your cool hero. Silence conveys menace, and menace is what the cool hero is particularly good at. Mostly what comes out of this one’s mouth is the formula containing the terms on which he will take on a driving job, which he recites as by rote, and the toothpick he chews on like Clint Eastwood’s small cigar in Fistful of Dollars.

He also resembles that other man with no name in having a sense of chivalry, which is evoked by Irene (Carey Mulligan), a neighbor in his shabby L.A. apartment building and a poor, down-on-her-luck young mother whose husband, Standard (Oscar Isaac), is in prison. Their chaste courtship amounts only to a pas de deux of attraction, and it also takes place in near total silence, though with lavish visuals of longing. When the husband comes home, the driver is drawn into an elaborate criminal enterprise for the sake of the girl — who really does appear childlike herself — and her son at peril of his own life and budding career as a race-car driver. It seems almost churlish to complain that this criminal plot is among the narrative details which the film declines to spell out for us, but that’s pretty much the way it is always going to be with the cool hero, since part of what makes him cool — like Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep — is that he can effortlessly understand what we, the audience, are deliberately deprived of the means to understand for ourselves.

One bad guy, improbably named Nino (Ron Perlman), has got hold of some money belonging to the Philly mob, partly for investment purposes and partly out of revenge for their having called him a kike to his face. Another bad guy named Bernie (Albert Brooks) is both Nino’s henchman and an investor in the driver’s prospective career as a race car driver. Coincidentally, Standard is the patsy — along with Blanche (Christina Hendricks) — in a staged robbery by yet another bad guy named Cook (James Biberi) with connections to Nino and Bernie. But how they got the money, what, exactly, the faux robbery is meant to accomplish or what the connection may be between these various bad guys, both on and off screen, is not spelled out. Clearly, Mr Refn and his screenwriter, Hossein Amini (adapting a novel by James Sallis) don’t hold with the Occamist principle that entities must not be multiplied unnecessarily.

The bad guys are not there for the sake of their own incomprehensible criminal enterprise, however, but only to provide a series of progressively more dangerous challenges to our cool, nameless hero and his car in their quest to save the pretty neighbor and her adorable child from even more shadowy evil-doers. The film itself, in other words, is a bit of a staged robbery in which we are the patsies, though we are used by now to being told by Hollywood that we don’t need to trouble ourselves anymore with plausible real-world explanations for what is happening on-screen. It’s not supposed to be like the real world, silly. That’s why the director has taken such trouble to make it look like a movie. The cinéphile doesn’t mind this, of course, since movies and, therefore, movies about movies are his thing. Increasingly, they are everybody’s thing, though they’re still not mine.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.