Entry from September 14, 2011

In a recent issue of the London Daily Telegraph Michael Simkins wrote of the contrast between British and American humor that,

However much editors may gaze longingly at the US and its sanitised, sassy sitcoms, sauce has long been the bedrock of both British humour and culinary heritage. From Chaucer, through Shakespeare and music hall to the Carry On films, a good sprinkling of innuendo has always been an essential ingredient of British comedy.

Doubtless it slipped his mind that “sassy” is a demotic form of “saucy,” the adjectival derivative of “sauce.” So does British “saucy” not mean the same thing as American “sassy”? To my ear, “saucy” is sexual, “sassy,” not. Perhaps this is because “sassy” in American usage is more often associated with children “sassing” their parents than with people being sexually provocative, which is, or used to be, in the ordinary semantic field of “saucy.” The OED, however, lists the first metaphorical meaning of “saucy” as follows: “Of persons, their dispositions, actions, or language: Insolent towards superiors; presumptuous. Now chiefly colloq. with milder sense, applied to children and servants: Impertinent, rude, ‘cheeky’.” The first citation is from Palsgrave in 1530, but a note observes that in the 16th century it was often in combinative forms such as “saucy (and) malapert, whence More’s ‘sauce malapert’” — that is, a figure of rhetoric denoting insolence.

Shakespeare provides the first two citations for “saucy” with the meaning “wanton, lascivious” — one from Cymbeline and one from Measure for Measure — and another Shakespearean meaning, now obsolete, applies the word to boats in the sense of “presumptuous” or “rashly-venturing.” Between the two, there is an ironic meaning dating back to Swift’s Journal to Stella of 1710 which the top lexicographers take to be “often” if not the most often contemporary usage “in mock dispraise, as an endearing or admiring epithet implying piquancy or sprightliness.” This I take to be the same as “sassy” — which OED identifies as “orig. and chiefly U.S.” meaning “Impudent, saucy, ‘cheeky’; outspoken, provocative; conceited, pretentious; self-assured, spirited, bold; vigorous, lively; stylish, ‘chic’.” It’s not quite clear to me why “cheeky” and “chic,” the near homophones in that list, are placed in quotation marks — perhaps to indicate that they come from a lower, more colloquial register than the surrounding words.

Why didn’t the sexual connotations cross the Atlantic? How were they cut down along with the length of the vowel? This takes us back to Mr Simkins’s observation that “sauce” is distinctively British. If so it is the product of repression. I remember a play by Alistair Foot and Anthony Marriott that ran for most of the decade of the 1970s in London’s West End (it flopped on Broadway) called “No Sex, Please, We’re British.” The idea seems altogether quaint now that sex is rampant in the British media (and elsewhere, one supposes, on the scepter’d isle) but back then it was how the British liked to see themselves: that is, in terms of the Victorian sexual repression they were then still reacting against. To this day, if people want to misbehave sexually they often portray themselves as revolutionaries against the long-dead conventions of those antimacassar-laced Victorian parlors, though the pretense is beginning to look a little threadbare.

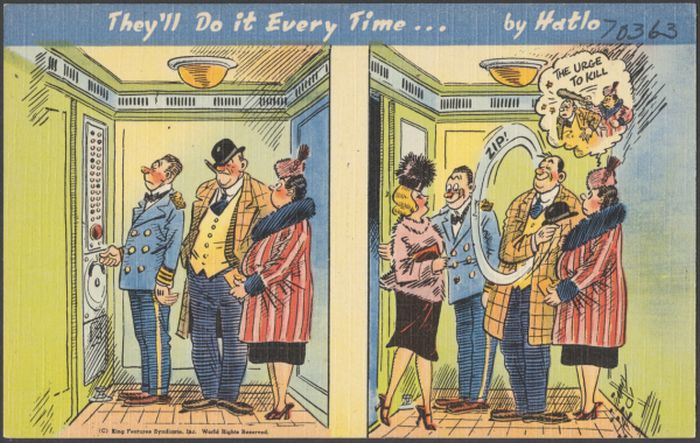

But the word “saucy” is a reminder of a time when rebellion involved real risks, real “transgressiveness” against powerful custom and convention, a time when the unofficial culture ran not far beneath the official one instead of overwhelming it as it has done in recent times. But the gusher of sexual unrestraint, rhetorical if not actual, that has taken place in the last 40 years, has robbed British sauce of its piquancy. Innuendo as it used to be found in the music hall or seaside post cards (or even the Carry On films) was often fun; open raunch rarely is. There’s a word, by the way, that OED also lists as “chiefly U.S.” Originally a war-time term meaning “shabbiness, dirtiness, grubbiness,” raunch took on its current and unambiguously sexual meaning also in the 1970s. It’s what we have in place of “sauce” on both sides of the Atlantic now, and it should probably take the place of sauce — obsolete as thing if not as word — in the interests of precision.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.