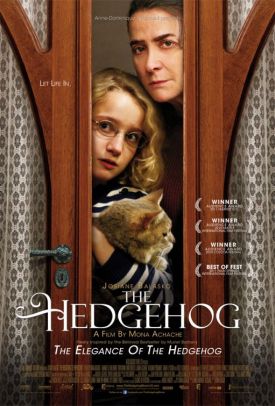

Hedgehog, The (Le Hérisson)

There’s more than one kind of movie fantasy destined to end up in the DVD bargain bin, and The Hedgehog (Le Hérisson) by Mona Achache is a peculiarly French kind — though perhaps the director herself sees it as more Japanese. It is, at any rate, an intellectual’s fantasy, embodying as it does the belief that, secretly, those noble proletarians and children of toil in whose name so many of one’s utopian projects are undertaken and, occasionally, executed are really intellectuals too, just like one, aspiring to live the life of the mind, of art and culture while being kept down by the jackboots of the bourgeoisie on their throats. As a result, they suffer the indignity of having to pretend to be stupid and boorish and intellectually incurious when in fact they are highly cultured — rather like film-makers or professors of gender studies at the university. As Ms Achache’s heroine, Renée Michel (Josiane Balasko), puts it: “Nobody wants a pretentious concierge.”

Therefore, Renée herself keeps her taste for the finer things of life out of sight. Even her extensive and very high-brow library has to be kept hidden behind a curtain in her little concierge’s flat so that casual visitors will not notice it. This is because they, and especially those who are residents of her upscale Parisian apartment building, prefer that the concierge should live up to the stereotype by (as she says) being fat and surly and stinking of cassoulet. So she obliges them, all the while keeping her more refined and intellectual tastes, like the library, out of sight. Now I would hate to be thought of as being unkind or contemptuous to concierges, but I venture to suggest that the fat, surly and cassoulet-scoffing sort without any intellectual hinterland is a good deal more common even in France — as is her equivalent is in the U.S. — than the secretly refined and intellectual sort.

But left-wing intellectuals, who may be even more common in France than in the U.S., prefer to entertain themselves with fantasies of workers and peasants who are, beneath their slightly rough exteriors, exactly like themselves. Such, I take it, is Muriel Barbery who wrote the book (L’élégance du hérisson) on which Ms Achache’s film is based. One reviewer has compared the latter to Babette’s Feast “in which the hard-bitten residents of a village savor gourmet food for the first time” — though of course the appeal of gourmet food is likely to be a little more widespread than that of the Japanese aesthetics of Junichiro Tanizaki’s Éloge de l’ombre, which is the light reading of Madame Michel — or even than that of Tolstoy, whose Anna Karenina is what brings her together with Kakuro Ozu (Togo Igawa). Mr Ozu is a courtly Japanese gentleman who has lately moved into the building. He immediately spots Renée’s secret intellectual life because of her allusion to that novel’s famous opening sentence about happy families’ being all alike.

I’ve never understood that line, by the way. It seems to me patently false. Tolstoy as novelist must have been as bored by happy families as the film’s ostensible subject, who is eleven-year-old aspiring documentary film-maker Paloma Josse (Garance Le Guillermic), the younger daughter of one of the families in Madame Michel’s building. Paloma’s family may not be all that happy, but it’s a cinch that it is happier than she wants us to think it is in her snarky voiceover comments about her mother, father and sister. She grabs our attention at the outset by telling us, also in voiceover, that she plans to kill herself on her twelfth birthday. To this end she is pilfering her mother’s anti-depressants, one by one, until she thinks she has stockpiled enough of them to do the job. “Planning to die doesn’t mean I let myself go like a rotten vegetable,” she confides to us and her father’s videocamera. “What matters isn’t the fact of dying or when you die. It’s what you’re doing at that precise moment.”

That’s an even more fatuous statement than the one about happy families being all alike, though sounds as if it came from an 11-year-old all right — someone for whom death is still something theoretical rather than real. But I have an awful feeling that it is meant to be a profundity. At any rate, it gives us one reason why this bright and apparently sane and emotionally stable prepubescent child should want to kill herself, which is something at least as improbable in real life as an intellectual concierge. Another, even feebler reason is that Paloma thinks she and her family live like her sister’s pet goldfish and “the fishbowl isn’t for me.” The point, I guess, is confinement and not transparency, as this has no obvious implication for Paloma’s life more than anyone else’s. She sees through others, or thinks she does (I’m guessing that Ms Achache thinks so too), but they don’t see through her. But why does what she sees in her family and those around her produce such contempt for them that self-slaughter seems the only way out?

The goldfish bowl, that is, is a seriously stressed metaphor even before we get to the symbolic implications of the real one with the real fish in it to which Paloma gives one of her mother’s anti-depressants as an experiment. Overburdened symbolism is another way in which this is an intellectual’s movie, along with its self-indulgence in a favorite intellectual fantasy and the fact that everything about it is so theoretical. The idea appears to be that life is only worth living because of the secret parts of it, that which lives out of sight in the delights of privacy where anything is possible and not in the dreary world of the goldfish bowl where everything is so obvious and, therefore, terminally boring. Here, however, even the goldfish has a secret, and Paloma’s friendship with the secretive concierge, her delighted discovery of what remains hidden from her boring bourgeois parents, is meant as an affirmation of life. I’m not buying it myself, but then I don’t think her bourgeois parents can really be as boring as Paloma — like Ms Achache and Ms Barbery — thinks they are either.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.